Uganda registers first Sickle Cell disease cure

Byamukama becomes the first Ugandan to be cured through gene editing. In 2008, seven-year-old Miriam Mulumba became the first Ugandan to be cured of the condition, but through a bone marrow transplant.

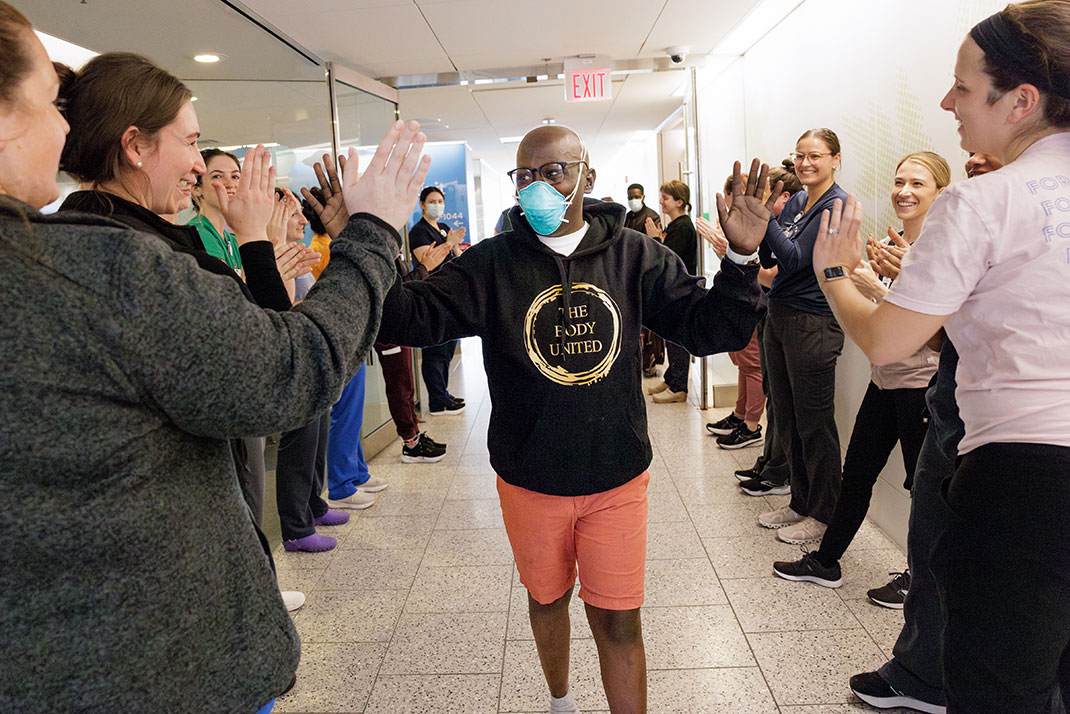

Byamukama with doctors in hospital during treatment, and he becomes the 15th person worldwide to be treated using the gene therapy method that was approved by the Food and Drug Administration of the US in December 2023.

At 35, Allan Byamukama’s life had been defined by pain and regular hospital visits because of sickle cell disease.

Diagnosed with the condition at five months, emergency units of health facilities in Uganda and the US had become his second home.

He had several forms of treatment, including hip replacement and red blood cell exchange, but little improvement was registered.

In the first 25 years of his life, his condition was being managed in Uganda until 2015, when he moved to the US where part of his family was living.

“When I moved to the US in 2015, a new form of sickle cell treatment known as gene therapy was still on trial. My haematologist recommended that I undergo this form of treatment after the US Food and Drug Administration approved it. After a lengthy procedure in laboratories and hospitals, the doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital declared me free of sickle cell disease in August last year, and indeed I have not had any complications since then,” he says.

Byamukama becomes the first Ugandan to be cured through gene editing. In 2008, seven-year-old Miriam Mulumba became the first Ugandan to be cured of the condition, but through a bone marrow transplant.

Overall, Byamukama is the second Ugandan to be cured.

He was the 15th person worldwide to be treated using the gene therapy method that was approved by the Food and Drug Administration of the US in December 2023.

Byamukama leaving hospital in the US.

Speaking to New Vision at the office of the Director General of Health Services in Kampala on Thursday, Byamukama could not hide the joy of getting a new lease of life after years of surviving on heavy doses of painkillers and constant treatment procedures.

“I could not believe it when the doctors broke the news. I had asked God to at least grant me a pain-free life of one year before I die. But he has done more than that, and I am grateful to him,” he said.

About gene therapy

Gene therapy is a cutting-edge medical approach that treats or prevents disease by correcting or altering a person's genetic material (DNA or RNA) to change how cells function, often by replacing faulty genes, inactivating harmful ones, or adding new genetic instructions to achieve particular results

Expensive, painful

Byamukama’s treatment did not come cheap; it cost a whopping $2.1m (about sh7.5b) and involved a process known as stem cell harvesting and cells editing.

“The cost of my treatment was covered under insurance in the US. This would have been impossible in Uganda,” he narrated.

Byamukama says in 2024, he was admitted in the emergency unit 42 times in March 2025.

The first procedure involved stem cell harvesting from his own body, which took three days.

“It is the cells editing that took about seven months. I then rested and the edited cells were again reintroduced back into my body. I underwent a short chemotherapy, and after a while, I was tested and found to be sickle cell free,” he said.

Byamukama posing for a photo with Dr Olaro (second-right), Mwesigwa (left) and another official.

Message to people with Sickle Cell disease

Byamukama encouraged people with sickle cell disease not to lose hope, explaining that the experts are working hard to ensure that remedies are available.

He also appealed to the Government and other stakeholders to ensure that the cost of treatment and groundbreaking procedures, such as gene therapy, are affordable.

“When I was a child, I thought I could not make it to 18, but here I am at 35 and free of sickle cell disease. I appeal to the Government to do more sensitisations and avail treatment in lower health facilities. There are areas in Uganda where people with sickle cell disease still depend on paracetamol to manage sickle cell disease,” Byamukama stressed.

Evelyne Mwesigwa, the Joint Clinical Research Centre Co-ordinator for Gene Therapy Initiative, welcomed the news of Byamukama’s healing and appealed to the Government and other stakeholders to lower the cost of treatment, and ensure that more Ugandan doctors are trained in such groundbreaking treatment procedures.

“Together with the Government and other stakeholders, we can lower the cost of treatment so that we save more lives. And it is possible. In the past, the cost of bone marrow transplant was over $1m (sh3.6b). Today it is about $30,000 (sh100m). Once the technology becomes affordable, more people will be saved,” she said.

Uganda’s efforts

Dr Charles Olaro, the Director General of Health Services, said the Government is committed towards lowering the cost of sickle cell remedies and eradication of the disease through a multi-pronged approach.

He said the Government is encouraging couples to test for the disease before marriage so that they avoid bearing children with the condition.

“The tests are free at all government health facilities across the country. We encourage pre-marital sickle cell tests so that couples do not find themselves in problems. It is only when you get a child who is has sickle cell that you will understand the burden of this disease. You will be in and out of hospital,” he said.

He also revealed that the Government is working with the private sector and development partners to lower the cost of the disease.

In October, health minister Dr. Jane Ruth Aceng announced that Ugandan pharmaceutical company Qcil will soon begin manufacturing hydroxyurea for sickle cell disease.

She said having the drug produced locally will make treatment more accessible and easier for those affected.

"This is a significant milestone in our history, and we are grateful," Aceng said.

Testing

Sickle cell testing is free of charge in all government hospitals for new borns and not more than sh50,000 for adults and in private sector.

Byamukama is the first Ugandan to be cured od sickle cell disease.

National burden

During World Sickle Cell Day in June, the Ministry of Health issued a renewed call for Ugandans to know their sickle cell status before bearing children, citing the latest estimates that reveal between seven to eight million people are carriers of the sickle cell gene.

Dr Charles Kiyaga, who heads the Ministry’s Sickle Cell Programme, revealed in an interview that this high number of carriers is not necessarily alarming, but could pose serious consequences if left unchecked, particularly among couples planning to have children.

“A carrier is not a sickle cell patient. They are healthy individuals with one mutated gene, inherited from either parent. But if two carriers marry and have children, there is a high risk of passing on the full-blown sickle cell disease to the offspring,” he told New Vision.

According to the Ministry’s data, the national sickle cell carrier rate was estimated at 13.3% in the 2014 national survey.

However, more recent findings from just targeted newborn screenings suggest the actual national prevalence could be more than 15%. Some regions, such as Lango, Acholi, and Busoga, are seeing even higher rates — as high as one in four people carrying the gene.

Kiyaga noted that due to expanded hospital-based screening initiatives — including free services at Mulago Hospital and other regional referral facilities — more Ugandans are discovering their status, something that was previously unknown due to limited diagnostic infrastructure.

But the burden remains. Uganda still records over 2,000 babies born each year with sickle cell disease, many of whom face repeated hospitalisation, pain crises, and premature death if not properly managed.