Fighting crime with halfway homes

Kateregga was arrested and taken to Bukuya, Kasanda district Police station. He was later arraigned before the Mubende Chief Magistrate’s Court on charges of theft of a motorcycle and sentenced to six years.

Located in Mukono district, the halfway home provides rehabilitation and counselling and helps them acquire income-generating skills. (Credit: Petride Mudoola)

By Petride Mudoola

Journalists @New Vision

KAMPALA - On December 28, last year, Emmanuel Kateregga, 24, walked out of Muduuma prison in Mpigi district.

He was given only sh19,500 for transport to get to his home in Kinoni village, Masaka district. He needed sh80,000 for the journey. Since the money was not enough, he opted to walk most of the way.

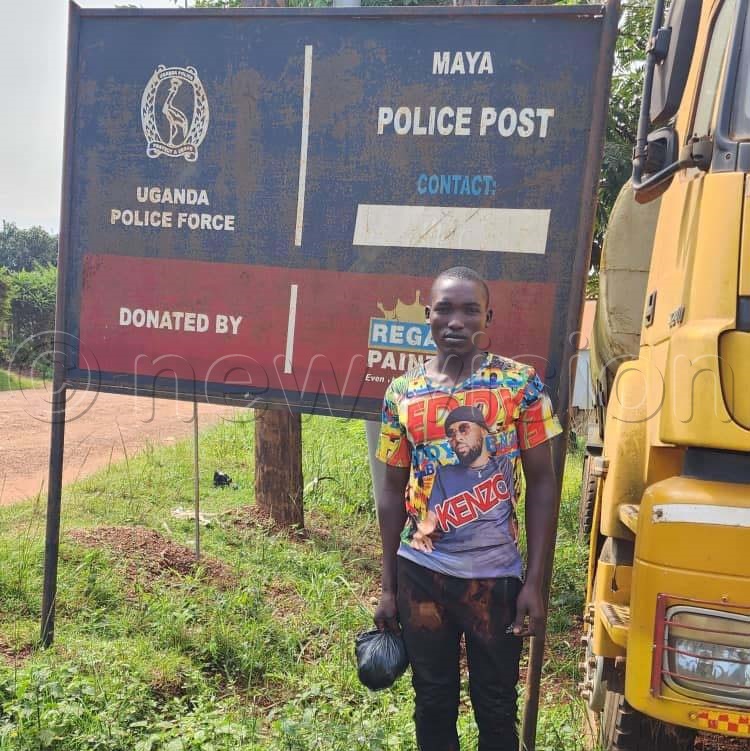

The fifth night of his trek found him in Maya, on Masaka Road. He entered an abandoned building to sleep, but he was mistaken for a thief and attacked.

He tried to explain his plight and even produced a prison release document, but his pleas fell on deaf ears. He was then taken to Maya Police Station to record a statement and was charged with trespass.

Thankfully, one onlooker who had seen Kateregga being beaten contacted Shadrack Magara, the founder of Pacem Havens Foundation, a halfway home for ex-convicts, to come to Kateregga’s rescue.

The Oxford dictionary describes a halfway house or home as a centre for rehabilitating former prisoners, psychiatric patients or others unused to non-institutional life.

Magara arrived at the Police station and convinced the officers to release him to his care, after explaining that he had just been released from prison and was heading home.

The officers studied the release form before handing him over to Magara. Kateregga spent the night at the halfway home, before being driven home to Kinoni.

“I had lost hope of ever seeing my son again,” Kateregga’s mother, Christine Munsabire, cried upon seeing him. “I have had sleepless nights, wondering what might have befallen my son in prison. Now that he is here, I give glory to God,” she said, before handing her son a hen to celebrate his return.

How Kateregga met jail

Kateregga left his mother’s hometown of Kinoni. He ended up working in gold mines in Mubende district as a gold purifier, a job he performed with determination.

August 17, 2022, began as a normal day for Kateregga, unaware that it would land him in prison. His employer’s motorcycle had gone missing and he was the main suspect.

Kateregga was arrested and taken to Bukuya, Kasanda district Police station. He was later arraigned before the Mubende Chief Magistrate’s Court on charges of theft of a motorcycle and sentenced to six years.

One way to help ex-convicts handle the struggles with reintegration into society, for Kateregga, Kamya and Nantumbwe’s struggles, is halfway homes. (Credit: Petride Mudoola)

His sentence was reduced to two years and he was transferred to Muduuma Prison.

“Although I was in prison, I never missed a meal, nor did I fail to take a shower. But after my release, I struggled to access water or food. I was forced to pick leftovers from trash bins,” Kateregga says.

What he experienced is not a new phenomenon. It is common for former convicts to struggle to get reintegrated into society.

Change of environment

Fred Kamya, who served a 12-year jail sentence for robbery, says he secured three jobs but was fired once his employers learnt of his criminal record.

“I enrolled in school while in prison; I hold a diploma in entrepreneurship and small-scale business management, but after being fired three times, I wonder what’s the point of getting further education while in jail, if your past will prevent you from getting work?” Kamya says.

Employers see employing ex-offenders as risky. “But how can people like me fend for ourselves if we cannot find employment? Doesn’t this prejudice us to a life of continued crime?” he asks.

Similarly, Florence Nantumbwe, who served a 22-year sentence for murder, reveals that her struggles are just as challenging, albeit of a different nature.

“It is until you are locked up that you realise there is more need for counsellors than doctors. I am so stressed because I feel strange being out in the world. Many things are difficult for me,” she says.

Nantumbwe adds that her struggles are exacerbated by the fact that she does not have the finances to deal with the change.

Need for halfway homes

One way to help ex-convicts handle the struggles with reintegration into society, for Kateregga, Kamya and Nantumbwe’s struggles, is halfway homes.

“Re-establishing yourself in society without being judged is a struggle. While in prison, their socio-economic activities are destroyed, to the point that nobody is willing to employ a former prisoner,” Magara says.

Magara, an ex-convict who spent 25 years in Luzira Prison, Kampala, says the project is personal for him, because he knows first hand the challenges former prisoners face once they are released.

Located in Mukono district, the halfway home provides rehabilitation and counselling and helps them acquire income-generating skills.

“We have an overwhelming demand for space. We cannot handle the number of ex-convicts who need us until we get adequate structures,” Magara says. On average, they get 30 ex-convicts per month.

There was just one other halfway home run by an non-governmental organisation, Mission After Custody, which closed due to financial constraints.

Magara says Pacem Havens Foundation needs sh750,000 per month to ensure ex-convicts are adequately skilled before they get back into society.

Due to lack of funding, the foundation only handles emergencies, where an ex-convict has nowhere to go.

“Ex-convicts, who are unsure of where to pick up life after they are released, will commit crimes after leaving prison so they can be re-admitted. In jail, they have friends, they are provided with free food, medication and education, which they cannot afford on their own once out,” Magara says.

He emphasises the importance of skilling ex-convicts at halfway homes, teaching them how to set up income-generating activities.

“This way, they can create their own employment instead of seeking jobs that they might be denied due to their past,” he says.

The necessary structures include a bakery, shoe workshop and craft facilities. Currently, the halfway home offers life skills workshops focused on job acquisition, maintenance and financial literacy, among others.

Additionally, the organisation has partnered with the Uganda AIDS Commission to provide HIV/ AIDS awareness and mental health counselling for ex-convicts.

While in prison, convicts acquire skills and at the halfway home, they receive counselling and job placements in farms, industries and professions, such as mechanics, plumbing, carpentry, cosmetology and information technology.

Prisons publicist speaks out

Recidivism is the number of times a prisoner re-offends and returns to jail. The overall factor is that many of them are rejected by the community they once lived in, Frank Baine, the prisons’ publicist says.

The African Journal of Criminology and Justice report of 2020 indicates that with a re-offending rate of 32%, Uganda ranks fourth globally.

Baine says re-offending is higher among cases of robbery, defilement and drug trafficking. He says re-offending is worse in situations where ex-convicts are rejected by the community where they once lived.

They, therefore, recommit crimes so that they can be sent back to prison. Baine says inmate leaders who are recognised as “Katikiro” receive preferential treatment while behind bars, which they fear to lose. So once out, they re-offend.

“Communities that ignore former convicts are responsible for recidivism because they force ex-convicts to seek acceptance in jails where they have friends,” Baine says.

Inside the mind of an ex-convict

Dr Ivan Mugabe, a senior psychologist attached to Mulago Hospital, says the prison environment is different from mainstream society, which is why ex-convicts struggle once they are released.

“Given the dynamic and ever-changing nature of society, ex-offenders, who spend long periods in jail, are released into a setting very different from their former environment, posing serious challenges for reintegration of offenders,” he says.

Mugabe calls upon Government and partners to come up with schemes that support resettlement of ex-convicts.