Citizen's manifesto: Voters ask for more action on wetland degradation

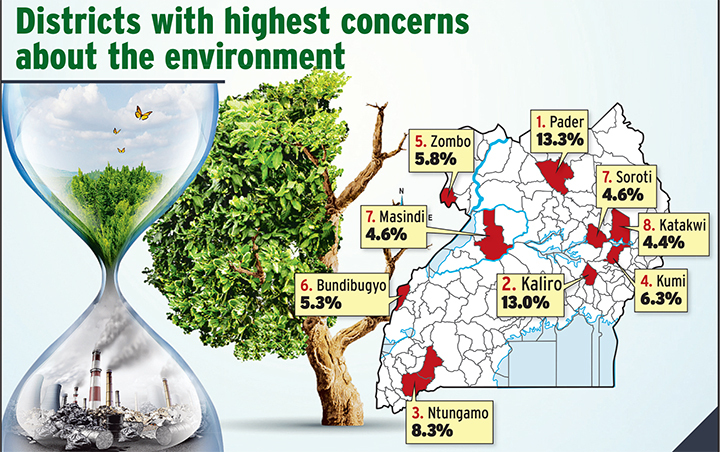

In an opinion poll conducted by Vision Group in March, ahead of next year’s general election, Ugandans shared 20 of their most pressing concerns. Environment-related issues were among the most pressing for voters.

On January 8, 2005, environmental inspectors from the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) demolished a house belonging to former Kampala Central Division mayor, Godfrey Nyakaana.

The house, that was in Bugolobi, Kampala, was said to be in a wetland.

This came after the inspectors gave Nyakana 21 days to bring down the house and restore the wetland, in vain.

As a result, Nyakana petitioned the Constitutional Court, challenging the demolition of his house, but he lost the case.

A dissatisfied Nyakana then petitioned the Supreme Court, challenging the verdict. However, the Supreme Court upheld the Constitutional Court ruling.

Unfortunately, NEMA's demolition of Nyakana's house has had little impact in deterring people from encroaching on wetlands. Thousands of acres of wetlands continue to be destroyed every year.

"They operate like thieves in the night, as you rarely hear or see them come. It is only after you wake up in the morning that you will see their prints. In the case of the thieves, you will notice a broken windowpane or padlock or the missing household items. In the case of wetlands, you will see mounds of earth and tyre treads," Peter Okello, a wetland conservationist, explains some of the tricks that wetland encroachers employ.

In 1994, wetland coverage on the surface area of Uganda was 15.6% but, over time, this has gradually reduced that by 2008, wetland coverage had fallen to 10.9%.

Collins Oloya, the commissioner for wetland management at the Ministry of Water and Environment, says currently, the coverage is at 8.9% and it is projected that by 2040, if nothing is done to stop the trend, Uganda will be left with only 1.6% of wetland.

"The changes are attributed largely to high population growth, expansion of land for agriculture, industries and urban expansion, as well as climate change impacts," Oloya says.

Vision Group poll

The Vision Group Poll conducted in March, across 45 districts, returned environment-related issues among the most pressing that voters want their leaders to address.

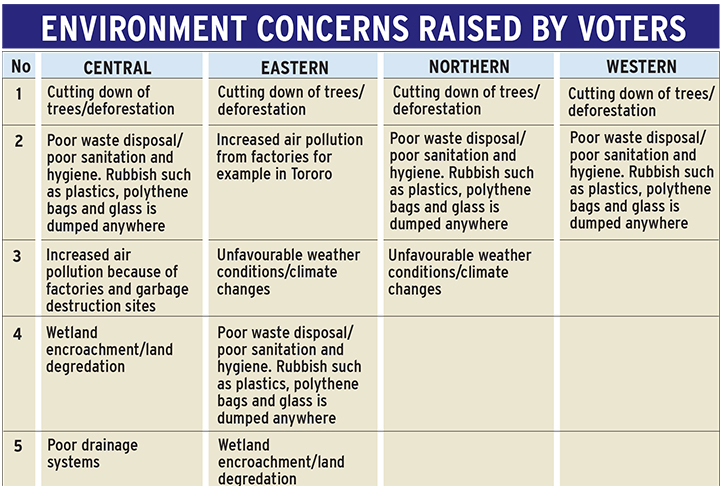

In the study, deforestation was a major concern across all regions. Other issues included poor waste disposal/poor sanitation and hygiene, increased air pollution because of factories and garbage destruction sites, wetland encroachment/land degradation, poor drainage systems and unfavourable weather conditions and climate change.

"A move to increase awareness of environmental conservation would be good to prove waste disposal habits, deforestation and reduce aspects of soil erosion. Education related to such programmes is key among communities," the survey recommended.

Scientists and conservationists agree that the current rate of wetland degradation is a national crisis bringing about catastrophes like floods and poor water quality emanating from their alteration.

Stephen Ssenkubuge, a conservationist and lecturer of environmental sciences at Makerere University, Kampala, explains that the most affected areas are around Lake Victoria and Lake Kyoga.

He says Uganda's water quality and quantity is compromised each day and that, already, many swamps and rivers are drying up because of the reclamation of wetlands.

"Cases in point are rivers Mpologoma on Mbale-Tirinyi highway in eastern Uganda and Rwizi, shared by Mbarara and Rakai districts, whose size and water quality and quantity are diminishing due to siltation caused by destruction of the neighbouring wetlands," Ssenkubuge says.

"Wetlands filter water of pollutants. The vegetation, especially papyrus, acts as a raw material in craft making and home for several creatures, like birds and reptiles that not only act as tourism attractions, but also balance the bio-network," Ssenkubuge adds.

Lubigi wetland

Across the country, many wetlands have been degraded. But experts argue that other than individuals, the Government has also been at the forefront of degrading wetlands, with Lubigi wetland in Wakiso standing out as the most stressed.

"In the last decade, the Government has undertaken several major projects on Lubigi wetland, among which was the Kampala Northern Bypass highway; the high voltage electric cables carrying power (132kV) from the Kawanda electricity sub-station to the Mutundwe sub-station; the National Water and Sewerage Corporation (NWSC) water treatment plant, which was built in the middle of the wetland, as well as the Kampala Entebbe Expressway. Such projects have stressed Lubigi's ecosystem," Peter Ekwanga, a renowned environmental activist, says.

Lubigi stretches from the northern to the western fringes of Kampala and benefits nearby communities in more than one way.

"Were it not for Lubigi, many homes in the surrounding would suffer from floods now and then. Some people who live nearby use the water from the wetland to make bricks for sale. The wetland also sieves out some of the pollutants say, plastic materials that have been carried from elsewhere," Ekwanga states.

However, the NWSC spokesperson, Samuel Apedel, explains that the Government approved the treatment plant after an environment impact assessment had been done.

"People need to understand the relationship between this plant and the environment. Why should we leave dirty water fl owing into Lake Victoria? This is a special plant that even collects faeces from latrines and it has reduced flooding in Bwaise," Apedel argues.

Individuals have followed the same path and reclaimed the important water catchment wetland that serves Kampala and Wakiso districts.

These pour soils in the wetland after which they construct houses, open washing bays and selling points in the reclaimed parts.

In other wetlands around the country, factories have been erected by investors after being approved by government agencies.

Need for swamps

Dr Krishna Sharma, a lecturer of environmental health sciences at Victoria University, Kampala, explains that wetlands are a critical part of our natural environment.

"They protect our shores from wave action, reduce the impacts of floods, absorb pollutants and improve water quality. They provide habitat for animals and plants and many contain a wide diversity of life, supporting plants and animals that are found nowhere else," he says.

"Take for example, improving water quality. As water moves into a wetland, the fl ow rate decreases, allowing particles to settle out. The many plant surfaces act as filters, absorbing solids and adding oxygen to the water. Growing plants remove nutrients and play a cleansing role that protects the downstream environments."

"On reducing the impacts of flooding, wetlands have the ability to absorb heavy rains and release water gradually. Downstream water flows and ground water levels are also maintained during periods of low rainfall. Wetlands help stabilise shorelines and riverbanks," Dr Sharma adds.

They are also an important wildlife habitat. Many wetland plants have specific environmental needs and are extremely vulnerable to change.

Some of our endangered plant and animal species depend entirely on wetlands. Sharma says wetlands are among the most productive ecosystems in the world, comparable to rain forests and coral reefs.

An immense variety of species of microbes, plants, insects, amphibians, reptiles, birds, fish and mammals can be part of a wetland ecosystem," he adds.

Anold Ssebunga, a resident of Nabweru, a Kampala suburb, says wetlands are a source of income since it is a breeding ground for mud-fish, a rich-in-protein delicacy which is sold at pocket-friendly prices.

"Wetlands also have papyrus which is used as a raw material for making mats and baskets which is also source of income for many households. Residents also cultivate yams on the fringes of the wetland," Ssebunga adds.

Government efforts

Over the years, many interventions to mitigate wetland degradation have been undertaken by the wetlands management department at the Ministry of Water and Environment, among which included the demarcation of critical wetland boundaries.

"In the last financial year, for example, over 5,000 pillars were procured and delivered to the various district local governments to mark specific wetlands earmarked for demarcation. A cumulative total of 480.39km of wetland boundaries were demarcated across the country, up from 226.6km, representing 96.1% of the planned target of 500km," Oloya says.

Oloya attributes this success to close involvement of the regional technical support unit and the district local government to undertake the demarcation process, as well as direct release of funds to the regions to undertake the tasks.

In the same vein, a cumulative total of 6,642.939 hectares of critical wetlands were restored across the country.

The restoration process followed the approved wetland restoration guidelines, where the involvement of all stakeholders is a prerequisite to ensure commitment and ownership, right from the inception to the final output.

"The restoration process started in 2012 and up to 16,906.5ha (1.9%) of the 865,700ha of the degraded wetlands have been restored," Oloya says.

The ministry is also equipping and sensitising stakeholders on the process of cancelling titles in wetlands.