Why land-hungry investors prefer to cut down trees

In the drive to get land under forests, sugar investors are promising to turn around the local livelihood of the population by providing employment, revenue from taxes and contribution to the socio-economic infrastructure.

ENVIRONMENT NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE

The fight between sugarcane investors and conservationists over forests is not about to stop.

To the investors, forests have no encumbrances, such as settlement areas, which would necessitate relocation of settlers and compensation, making it a costly project. As a result, they find it cheaper to cut down trees and embark on money-minting projects, ignoring environmental concerns.

Soil fertility is another factor. With their fertile soils, once the forests are cut, investors will not need to use fertilisers for a long time. This is a big saving.

In a recent statement, Sheila Nduhukire, the communications and public relations officer of Hoima Sugar, described her company as an environmentally-friendly one.

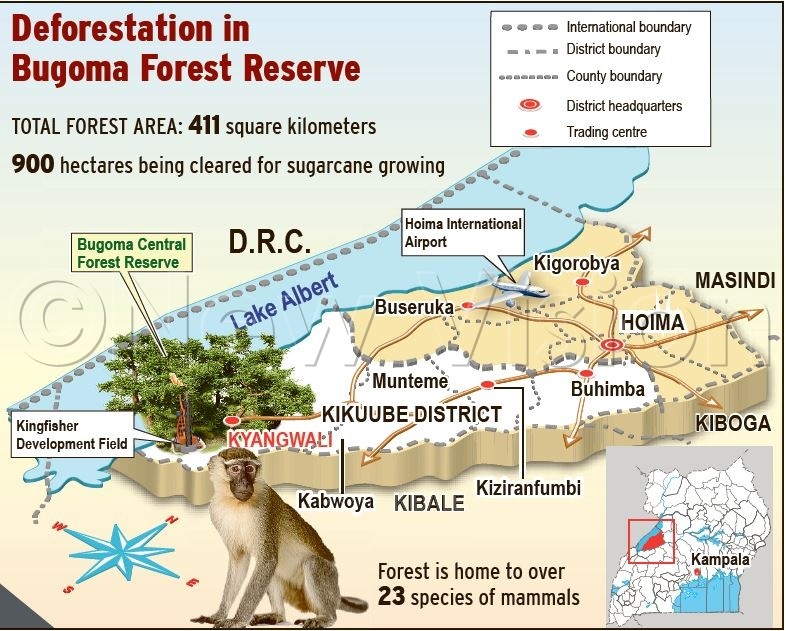

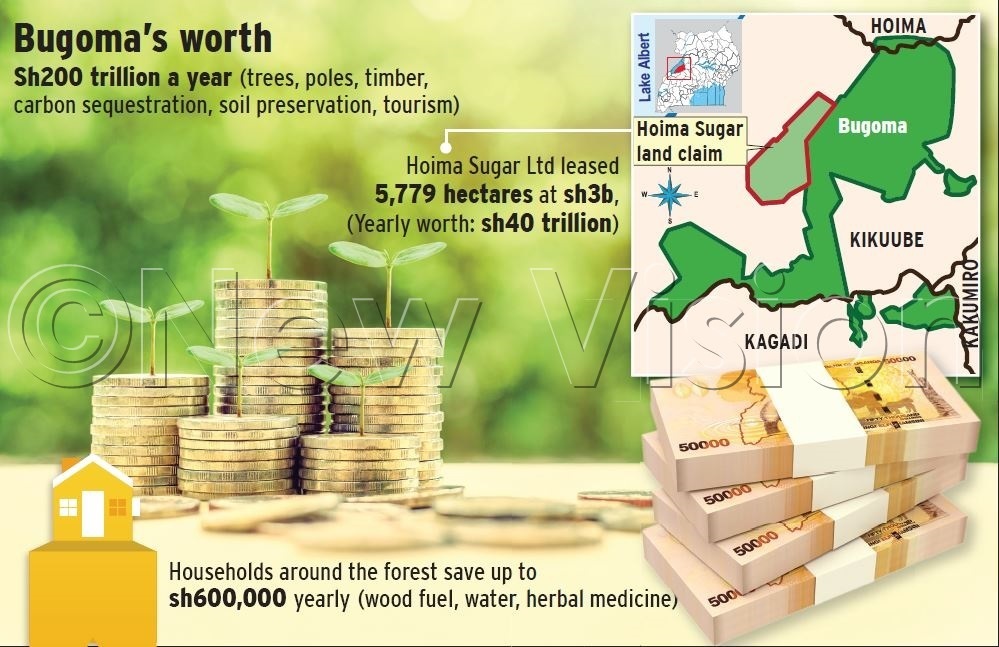

"The 22 square miles (5,779 hectares) that we got from Bunyoro Kingdom is not on a forest. We are a green company and there is simply no way we would want to cut down a forest," she said.

However, Gaster Kiyingi, the director of Tree Talk Plus, says any grassland in the forest is part of the forest's ecosystem.

"A grassland is part of the forest ecosystem," Kiyingi said, before adding, "You cannot use the existence of a grassland to give away Bugoma."

Kiyingi said the grassland in Bugoma would turn into woodland over time if left undisturbed.

"What sugarcane growers are doing is disturbing the ecological succession (the transformation of a woodland into a tropical high forest)," he said.

To conservationists, resisting such investors is standing up for nature.

They point to the ravages of climate change as a result of disregarding the value of forests and the environment at large, which includes failure to secure catchment areas of water bodies.

In the drive to get land under forests, sugar investors are promising to turn around the local livelihood of the population by providing employment, revenue from taxes and contribution to the socio-economic infrastructure. To some extent, they could, but with a heavy toll on the environment and the people.

The destruction of Bugoma could trigger many problems, for instance, decline in water levels is likely to disrupt the generation capacity of Kabalega hydroelectric power dam on River Wameabya, which is now producing 9MW.

"You should not expect to generate hydroelectric power on rivers that feed from the Bugoma catchment," Maxwell Kabi, the coordinator of forestry resources utilisation at the National Forestry Authority (NFA) said, before adding: "Lake Albert water levels are also likely to fall."

The oil industry has water-thirsty operations. The presence of the lake is a big advantage to the industry being developed in the region, but this may not be the case if the water volume dropped.

According to Sam Mwandha, the executive director of the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA), the investment in sugarcane growing is not a good idea.

"If that part of Bugoma is grassland, then we should discuss it, but if it is a woodland or forest, it is not a good idea to destroy it for sugarcane growing," Mwandha said.

Contrary to NEMA's declaration that the land covering nine square miles in Bugoma forest is grassland, on September 17, a team from Vision Group deployed a drone that captured images, including photographs and videos on the contested part of Muhangazima block in Bugoma Central Forest Reserve, which indicated otherwise.

Mwandha also pointed out that Uganda should harness its gifts in a sustainable way.

"We should not gain from growing sugarcane at the expense of the tourism industry, agriculture or the oil industry."

Cost of destruction

Bunyoro's land had remained intact for some time, but destruction has increased as more people get attracted by the oil industry.

"The interest for Bunyoro Kingdom has been conservation for a long time, but they are now shifting their interest to sugarcane growing," said Stuart Maniraguha, the NFA director for plantations.

According to Maniraguha, the Albertine rift still has large expanses of land suitable for agriculture, but Hoima Sugar prefers Bugoma.

Bugoma, which is one of the richest forest reserves in the country, has more than 600 endangered chimps.

It also houses the Nahan's Francolin, which is an endemic bird species only found in two other forests; Budongo and Mabira. The Nahan's Francolin, according to Achilles Byaruhanga, the executive director of Nature Uganda, is endemic and is found in Uganda and DR Congo's Ituli forest.

Bugoma, which is one of the largest forests in Uganda, also houses endemic monkeys (Ugandan Mangabey) that are found in few other areas, such as Mabira.

The destruction of the forests goes against many environmental protocols, including the Convention on Biological diversity to which Uganda is a signatory. It also violates the principles of sustainable development.

Sugarcane and poverty

Mwandha noted that before accepting to cede a forest to sugarcane growing, the people of Bunyoro need to understand that sugarcane growing is partly to blame for the poverty and depletion of the environment in Busoga.

Dr Edward Mwavu, a lecturer at the College of Environment, Makerere University, said sugarcane growing thrives on unfairness and exploitation of the weak and vulnerable.

Mwavu has already undertaken studies on the social, economic and environmental implications of growing sugarcane. He pointed out that sugarcane growing was creating enslavement to the big sugar millers.

"The people benefiting from sugarcane growing are not the ones who have an acre or two. It is the big landowners who have 20 or 30 acres and beyond," he said, adding that people are crammed on tiny pieces of land like tinned fish.

He also pointed out that most people have big families and they are living on one or two acres of land.

"People may be constrained on income and some rent out their land for medical attention. This means that during that time, they cannot engage in food production. Consequently, they suffer from food and income insecurity," Mwavu said.

The sugarcane trap

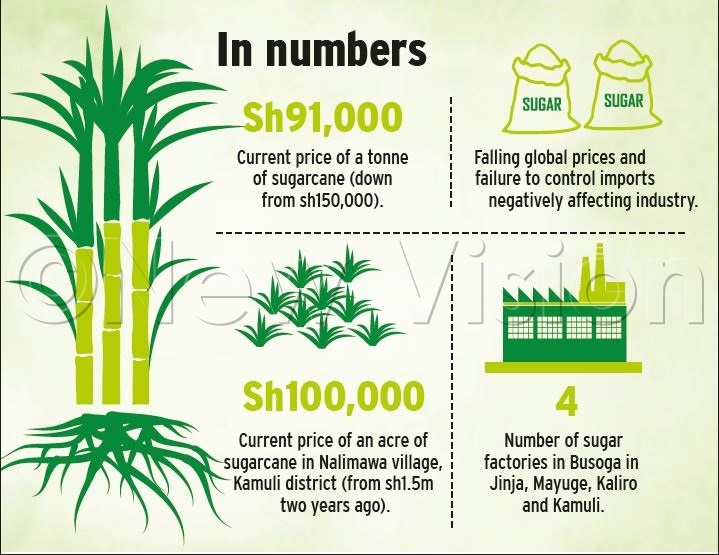

Robert Akugonza, an out-grower supplying Kinyara Sugar, said a tonne of sugarcane goes for sh91,000, down from 150,000, which was the price five years ago.

"The prices are very low yet we cannot easily switch to other crops.

"For us to recover our operating costs, the price for a tonne of sugarcane should be sh105,000. We have been trapped because sugarcane growing is not like maize, where you plant for one season and turn to another crop. The sugarcane plantations have to be maintained for about eight years if you are to make good money," Akugonza said.

He says there could be boom today, but this may not be the case in the future because farmers are being knocked out of business.

"In order to make money, big companies are getting their own land and also automating so that they can stay in business. But this is pushing people out of employment," he said.

According to Atugonza, conservation and sugar production are inseparable. "Good weather means better production, it also reduces the risk of fire outbreaks," he said, adding that they cannot rely on prayers for rain all the time.

Not sweet anymore

In a tiny village called Nalimawa in Kisozi sub-county, Kamuli district, Betty Tigawalana says they started growing sugarcane when one acre was going for sh1.5m-sh2m two years ago. Today, an acre of sugarcane goes for as low as sh100,000.

"We are stuck with the sugarcane plantation. I want the land free of sugarcane so that I can grow food crops," Tigawalana, who had planted two acres of the sugarcane, said.

She also said the land where sugarcane is cultivated used to support agro-forestry trees, which included maesopsis eminii, as well as ficus natalensis (barkcloth trees) and bananas. These, she says were cut to give way to a less rich monoculture - sugarcane.

"The land has become poor because the sugarcane drain a lot of nutrients from the soil and does not support pollinating insects, such as the beetles and bees that used to visit crops frequently," she told Saturday Vision in an interview last week.

According to Stephen Muwaya, the coordinator of Climate-Smart Agriculture, the sugarcane business concentrates processing of the cane in the hands of the investor.

"The investors apply persuasive means when spreading the gospel of growing sugarcane, but they are reluctant to pay the farmers when they get on board," Muwaya told Saturday Vision in an interview.

In Bugiri district, Silver Oboth says he declined to grow sugarcane and formed a co-operative with the local farmers who practise conservation agriculture. He said they have since increased their maize harvest from an average of 15 to 28 bags of 100kg.

Oboth says they grow enough food to eat and even sell some to farmers in places like Luuka, where sugarcane growing has taken over the landscape completely.

"We sell the food to Luuka residents," Oboth said.

Busoga has four sugar factories in Jinja, Mayuge, Kaliro and Kamuli. Bunyoro is walking on a similar path as three more factories are expected to be set up in the region.