COVID-19 uncovers deep-rooted gender inequality

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE |

The lockdown imposed in Uganda in March to stem the spread of COVID-19 will forever stand out as having exposed the deep-rooted gender inequality concealed in society.

In just one month after lockdown (March 30, 2020 to April 28, 2020), an estimated 3,280 cases of gender-based violence (GBV) were reported across the country. By the end of May, 5,538 cases had been reported to the Police, Sauti toll-free line and gender ministry database.

Think about 3,000 girls, forcefully married off, defi led or made pregnant. It is about two universities of girls molested.

It is a huge population. Women were sexually, physically and emotionally abused.

"COVID-19 has unravelled our system and unmasked our society to show that we are vulnerable. We now have evidence and

it's clearer that gender inequality is a big problem and we need to close the gap," Dora Musinguzi, a human rights lawyer and executive director of Uganda Network on Law Ethics and HIV/AIDS (UGANET), says.

"Cases multiplied by hundreds. Our national GBV database and the Sauti toll-free line were overwhelmed by cases being reported," Doreen Bakeiha, a gender officer in the gender ministry, says.

"GBV is a big problem in our midst. Nobody can say they are not prone, we are all susceptible, but there those who are more vulnerable," Musinguzi adds.

Why the concern?

GBV is a sexual, physical, economic, and psychological (or emotional) form of abuse subjected to an individual.

The lockdown has given male chauvinists an enabling environment to taunt and stress women, subjecting them to GBV, says Denise Tusiime, a member of the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC).

This was during her keynote online lecture under the topic: Addressing gender-based violence through gender equality under

COVID-19. This was organised by EOC and moderated by Sirabo Wafula, also a member of EOC.

GBV is both a human rights and public health concern. Women and girls have been maimed and there are both direct and indirect costs, with long-term effects on survivors, Musinguzi says. Disturbingly, although there are laws to prevent GBV, they have not been able to protect women and girls from violence.

Bridget, at only six years, was defi led during the lockdown in Toro. A child of a sex worker, the perpetrator assumed because of her mother's line of work, men were welcome to abuse any other female in the household.

Totally torn and rotting, she was only able to receive surgery after 16 days at Nsambya Hospital in Kampala.

The defilement of six-year-old Bridget during the lockdown, the marriage of a 12-year-old girl to a 52-year-old man in Iganga district during the same period is a hint of a bigger problem in our society.

From defilement, rape, child marriage, teenage pregnancy, to female genital mutilation (FGM) and physical violence, COVID-19 has wrought more problems for women and girls.

Much as both men and women suffered GBV during the lockdown, statistics show men are the biggest perpetrators of GBV and women and girls make up the majority of the victims.

Why the high level of GBV

It is the cultural and religious beliefs that elevate men above women.

"Our societies, even women, believe that it is okay for a man to discipline his wife," Musinguzi says.

"As long as a man is exerting his power over a woman, it is okay. That is what socialisation has done in a patriarchal (male controlled) society. We have grown to accept bad norms as normal."

Some men feel offended because they believe that when they speak in the home no one should respond. Responses spark GBV. "The power imbalances where men feel superior as entrenched in cultural norms has led them to act with impunity during the lockdown," Musinguzi says.

Also, the collapse of traditional society and family support systems where families were the concern of the entire community to individualistic living has escalated GBV.

The economic dependence of women on men, poverty, power and pressure have all instigated GBV.

"If we cannot tackle these issues we cannot do away with GBV. We must address the problem," she says.

What men should know

During the COVID-19 lockdown, there are some men who set themselves ablaze, killed their partners or took their lives because of GBV, Musinguzi says.

"These are issues women have been grappling with probably for their entire life with their partners, but when it comes to the men, they think it's unbearable.

"The same way men feel when emotionally neglected, when assaulted, when faced with economic violence is exactly what women feel and they felt that for so many years and with more consequences."

Damage and cost of GBV

The future of over 3,000 young girls forced into early marriages, teenage pregnancies, and defiled might be drastically changed.

"We are happy that schools might open soon, but there is a big number of girls (child mothers-to-be) who are not going to return to school. A number as large as over 3,000 girls whose future is hanging in the balance should be an issue for concern," Musinguzi says.

Also, GBV is a health issue. "We need to be thinking about the limbs that are broken, the mental anguish and desperation that comes out of GBV in many ways," she says.

GBV is not just a matter of two people or family or individual, the cost is borne by the country as whole, according to Bakeiha.

Direct costs include healthcare services. "Money is spent treating the victim," she says.

The victim is rendered unproductive (in the hospital they are not working) it impacts on earnings and GDP.

The judicial service, instead of attending to other cases, also grapples with cases of GBV, Bakeiha explains.

Social services are strained — in hospitals there are many other illnesses, but GBV cases also require attention.

"Indirect costs arise from loss of productivity, and not earning income. Children won't go to school as a result of a lack of school fees. With no money, one can't afford medical care.

"The effect is short and long term. The long term effect is more damaging, including loss of self-esteem," Bakeiha says.

Earlier studies indicated that the cost of violence against women could amount to around 2% of the global gross domestic product (GDP).

Here in Uganda, about 9% of violent incidents forced women to lose time from paid work, amounting to approximately 11 days a year, and equivalent to half a month's salary. With rising GBV, the cost could be higher.

Why we have failed

"The reason we have not scored 100% in responding to GBV is because of perpetrators threatening victims, especially those interested in following up the case to the end," Sophie Nambala, a Police officer, says.

Nambala is a Superintendent of Police in charge of the Child and Family Protection Unit in the Kampala Metropolitan area.

"If the victim is dependent on the perpetrator, they weigh what they stand to lose, including a home, a future for their children and withdraw the case against their better judgment," she says.

"Even if the Police push the case to court, when needed to testify, the victim will not come. Not because she is not interested, but because of the threats and pressure from home and relatives of the perpetrator."

Nambala says some of the Police officers have also not fully attained knowledge on fighting GBV and ask questions that demoralise victims from seeking justice.

Also, many cases reported do not go far because of logistics, lack of means to reach out to victims and no means to seek medical and legal intervention by victims.

Way forward

"Unless the public know that GBV is inhuman, highly punishable and see perpetrators punished, it will prevail," Bakeiha says.

It is important that the Justice Law and Order Sector takes GBV seriously, accord justice to survivors and send a stern warning to would-be offenders.

Some people commit GBV and are not even aware that it is illegal. For example, emotional violence even among the elites, including the name-calling, ignoring spouses, and children is a form of GBV.

"That power inequality and the power dynamics that make women a weaker group or sex is what needs to be addressed," Musinguzi says.

Male involvement

Pius Bigirimana, the permanent secretary to the Judiciary, who is also an advocate of women's rights, says there is need to promote male involvement in the fight against GBV because they are the custodians of traditions that foster it. Musinguzi agrees that the role of men in ending GBV cannot be ignored.

"We would like to see men come out to speak about GBV to inspire fellow men and make the public understand that masculinity can be used in a positive manner to support women and girls, who are sisters, mothers and wives, but not to inflict violence on them," Musinguzi says.

The world seeks to eliminate all forms of violence against women and girls by 2030 as one of the sustainable development goals.

The Uganda Police and gender ministry have in place a toll-free line 080019919524 to address issues of GBV and victims can report and get support 24/7.

The law and ending GBV

The Constitution in Article 32 and 33 provides for affirmative action and the right of women to equal treatment, says Pius Bigirimana, the permanent secretary and secretary to the Judiciary.

Article 33, Section 4 provides for equality and opportunities both in political, social and economic activities.

The Domestic Violence Act protects victims of domestic violence. From available statistics, 56% of those between 15 and 49 experience violence.

The FGM Act 2010 provides for the prosecution and punishment of offenders and the protection of victims.

The Prevention of Trafficking in Persons Act 2009 protects victims of human trafficking and provides punishment for offenders.

The Penal Code Act was amended to address defilement and provides punishment for all forms of GBV, including sexual harassment.

The employment, sexual regulation of 2012 prohibits sexual harassment at the workplace and provides punishment for offenders.

The Children's Amendment Act 2016 protects children from being abused, trafficked and exposed to all sorts of harassment.

The National Policy on Elimination of GBV in Uganda 2016 is the overall policy to prevent and respond to GBV, eliminate impunity, and foster zero tolerance to all forms of gender domestic violence. However, despite all these policies, women and girls have continued to be subjected to GBV.

"We have a high level of impunity of perpetrators of GBV who think they can get away with it," Bakeiha says.

A woman showing wounds on her back after she was burnt by her husband using a fl at iron. The Police say by May, because of the lockdown, they had recorded about 5,538 cases of GBV.

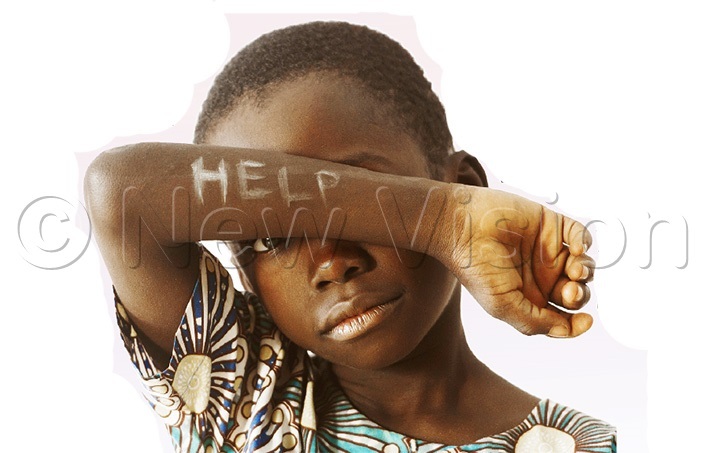

A sad child asking for help. The lockdown has seen victims of GBV trapped with abusers