How Davis Kamoga won an Olympic medal

He proved Atlanta was no fluke by winning silver the following year at the World Athletics Championships in Athens

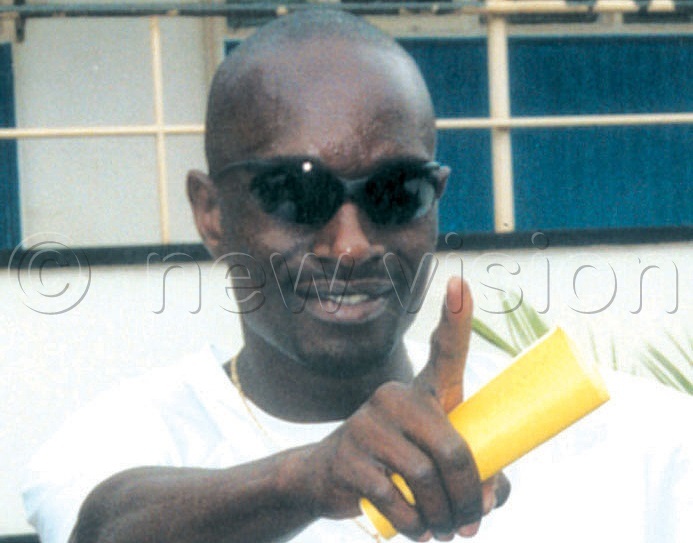

Perhaps nothing better captures the surprise surrounding Davis Kamoga's Atlanta Olympics bronze medal than an argument thousands of miles away in a Ugandan newsroom.

After Kamoga cruised to the final, an excited junior writer at New Vision urged workmates to start preparing for a medal-winning coverage of the men's 400 metre final.

"Kamoga will win a medal," the young writer kept saying. Then one editor, visibly irritated by the reporter's enthusiasm, indignantly dismissed the young writer as being too much of a dreamer.

The editor just could not imagine a Ugandan, the only African in that final, sharing the podium with powerhouses like USA, Great Britain and Jamaica.

Everyone in the newsroom took the widely travelled editor's word as the truth. The editor had swung the newsroom in his favour, but this support was not to last for long. Kamoga indeed, as foretold by the reporter, went on to win bronze.

Underdog

But maybe the editor's sentiments were understandable. Kamoga indeed took to the final as an underdog.

With an eighth-place semi-final finish at the 1995 World Championships as the biggest honour to his name, he was not expected anywhere near the Atlanta podium.

Kamoga's arrival out of virtually nowhere also had many doubting his abilities.

He was discovered well into his 20s by athletics coach Benjamin Longiros. The army coach was passing by a football training session in Jinja when a very fast winger caught his eye.

He invited him for athletics training. This was followed by entry to a national trial in Bugembe that Kamoga won in an impressive 47 seconds.

But perhaps those who cared should have taken Kamoga more seriously in the build-up to the Atlanta final. He had for starters set a national record at an IAAF Permit Meet in Nairobi.

Then in the 1996 games proper, he further exhibited steady progress.

Out of an entry of 64 runners Kamoga started off with a 44.56 time in the heats. He then raised the bar to a 44.85 national record in the quarter-finals before an even more impressive 44.82 semi-final.

But for the pessimists, Kamoga still had no chance.

Johnson gold favourite

For starters, there was US superstar Michael Johnson who was assured of gold. Then there was Briton Roger Black who to many was the sure bet for silver.

There was also another American star Alvin Harrison and Jamaican Roxbert Martin, who had not only been faster than Kamoga in the earlier rounds, but had equally been impressive before the games.

In the final, Kamoga's impressive show in the qualifiers was rewarded with a lane two placing.

That this was next to Black in three and Johnson in four, proved strategic.

Harrison was handed the dreaded lane one and Martin was in the much better five.

In the race proper, Johnson expectedly exploded from the blocks and cruised unchallenged to an Olympic record.

Tactical affair

But for the rest of the field, it turned out to be a very tactical affair. Kamoga was not about to be excited by the grandness of the occasion.

It was clear he was conserving his energy for the most important section of the race. Going into the final 100m he was last.

Kamoga then increased the pace. The strategy indeed paid off immediately as he sped past three competitors who were struggling for breath.

But with ten metres to go, he was in the fourth position with Harrison seemingly assured of bronze. Then Kamoga engaged another gear with five metres to go beating the American to the tape in a dramatic finish.

It was an agonising moment for Harrison as Kamoga won Uganda's first Olympic medal since boxer John Mugabi's silver at the 1980 games in Moscow.

On the track it had taken Uganda even longer to taste Olympic glory. John Akii-Bua, a gold medalist at the 1972 Munich Olympics in the 400m hurdles, had been the country's last athlete on the Olympic podium.

Kamoga proved Atlanta was no fluke by winning silver the following year at the World Athletics Championships in Athens.

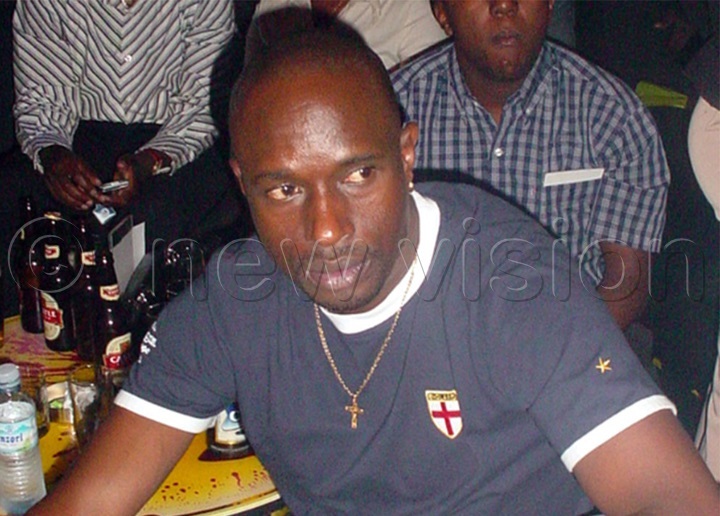

Success gets to Kamoga's head

Perhaps because of the rarity of Uganda's sports success at this level, Kamoga suddenly found himself in unfamiliar terrain.

He seemed not to know how to conduct himself. Then New Vision deputy sports editor Wangwe Mulakha who covered the Atlanta games was one of the first victims of Kamoga's behaviour.

Kamoga preferred giving interviews to foreign media at the expense of Ugandan journalists.

"It was a nightmare getting a word from him," recounts Mulakha, who instead had to plead with South Africa's Mark Gleeson to convince Kamoga for an interview.

Scoffs at USPA

In 1997 Kamoga at the peak of his powers refused to honour a Uganda Sports Press Association annual dinner to crown him as the sports personality of the year.

Sources close to him disclosed that he had scoffed at the top award of a black and white television set saying it was too cheap for his status.

Interestingly, the following year, successful rally driver and city businessman Emma Katto embraced the same prize. To Katto, who could effortlessly afford numerous of such TVs, it was not the price of the prize, but the spirit in which it was given.

Kamoga calms down

It took a lecture from yours truly for Kamoga to realise that Ugandan journalists mattered. This was after Kamoga being made aware of the fact that the same journalists he was despising had, before his arrival, interviewed bigger names like Akii-Bua, Mugabi and Ayub Kalule.