Akii-Bua: The hero was no coach

SPORT |

As a coach, the late John Akii-Bua had an effective way of getting his athletes' adrenaline churning ahead of a big race. The track legend would show the athletes a video clip of his world record 400 metre-hurdles race at the 1972 Olympics in Munich, Germany.

He would follow this up with a blow-by-blow account of the 48 hours before the starter's gun launched him to fame.

He would recall the calamities that befell him just hours before the race, almost forcing him to drop out: A nagging tooth that had to be extracted, leaving Akii with a swollen, throbbing gum. The doctor would not issue medicine to dull the pain lest it affected his form.

A cut on the knee, sustained during the heats, also could not be stitched because it would affect the hurdler's flexibility. Too nervous to sleep, Akii had to down a goblet of wine offered by his British coach Malcolm Arnold, to soothe his frayed nerves. He was also to run in lane one; not the most comfortable route for a 6ft 2in tall man with gangly legs.

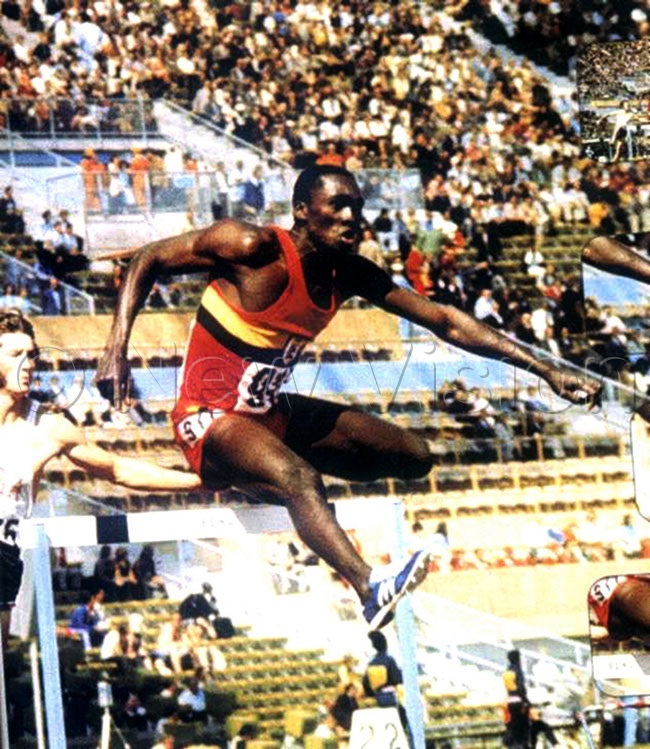

The obvious dark horse in a race of elites, Akii was ignored both by the TV camera crew and the commentators, until halfway through the race, when it became apparent that the Uganda actually intended to win, and win big. Then came the deafening cheers from the 80,000-strong crowd, as the Ugandan went for his victory lap, effortlessly clearing hurdles like he was just warming up for his race.

It did not matter how many times you watched the video recording of that race, or listened to Akii's accompanying account. Each time would leave you feeling feverish, just itching to take on the best on the track.

It is not for nothing that the 400m hurdles race is referred to as the "Man Killer" or "King of the Track". It is a tough race. To the runner, the next hurdle always appears to be an inch higher than the previous one, as the lactic acid builds up in the tortured muscles.

To become an accomplished quarter miler, you need a combination of stamina — both physical and mental — speed, strength, skill, and the ability to think on your feet. Akii had all these, and a physique to match. More than half his height was his legs, and he had a powerful chest to pump those lanky arms for extra thrust. Akii was well equipped for the toughest track event. He also enjoyed a few other advantages. For a man of his height, Akii was unbelievably flexible. One way in which he intimidated opponents was by bending and touching his toes while keeping his very long legs straight. That would be just before getting down into starting position. It never failed to work.

The other advantage, which some people considered a defect, was his inconsistent hurdling style. While most hurdlers can lead with only one leg, Akii would easily alternate between left and right. This can be an advantage if the hurdler miscalculates the distance between hurdles, and approaches the hurdle with the "wrong" leg. He can quickly adjust without chopping steps, and slow down.

Yet another advantage, if you can call it that, was his capacity for hard training. Akii had no off season. While other athletes enjoyed their offseason, Akii would be doing cross-country running or climbing hills with weights attached to his legs. He would even compete in cross-country races at the beginning of the running season.

None of his team-mates could keep up with Akii's training pace, which bordered on self-torture. But it paid off. Although he only became a household name after the 1972 Olympics, AMI had for some time been whittling away at the world record which he eventually shattered in Munich.

He had finished fourth at the 1970 Edinburgh Commonwealth Games in Scotland, and clocked some sensational times in 1971 and 1972, prior to the Olympics. These included an impressive 49.05 second (the world record then was 48.1 sees) in a US track meet.

Akii started out as a high hurdler (110m) and only switched to the low hurdles (400m) after failing to qualify for the 1968 Mexico Olympic Games in the 110m hurdles. Two years later, at the 1970 Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh he entered both events but failed to make the finals of the 110m hurdles race. In the 400m, he finished 4th in 51.1ses, well behind the three medalists. Thereafter, he concentrated his training on the 400m hurdles, and by the end of 1971, he had reduced his best time to 49.0secs.

As part of his preparation for the 1972 Olympics, Akii travelled to Munich early to train and acclimatize. About a week before the Olympics he ran a time-trial of 48.8secs, which greatly boosted his confidence.

While Akii had clocked 49.7 seconds on a grass track in Kampala and then 49 seconds in 1971 — the fastest time in the world that year — most experts felt that the mental and technical demands of three rounds in the Olympic arena would be too much; there was never a hint of the explosive run he would bring to the Olympic final. He was to prove all of them wrong. D-Day was September 2. Akii was drawn in lane one (despite clocking the fastest semifinal time of 49.25secs), with defending champion David Hemery in lane five and American Ralph Mann in lane six.

Running the 400m hurdles in lane one is every hurdler's nightmare, especially if they happen to be tall. The corners are sharp, so you have to use more energy to stay on course, and you are often forced to chop (shorten) your strides.

You also can't plan your race; you are forced to run flat out, in order to catch up with the rest of the competitors. The worst bit though is that you can't quite tell whether you are ahead or behind the rest, until you enter the home straight. Most runners prefer lanes three, four, five and six. Equally bad are lanes seven and eight because you are forced to run blindly, relying on your ears to monitor the activity behind you. Meanwhile, the runners behind you are using you as a target.

It therefore takes an exceptionally talented athlete to win a race, let alone break a world record, running in lane one. Akii did just that.

Ignoring the odds piled up against him, Akii jogged to the starting line with the confidence of a blind man approaching a cliff edge. Stretching his limbs in that intimidating way of his, he responded to the starter's call for the race to start.

Hemery set a blistering pace, determined to lead from start to finish. But while everyone focussed on Hemery, Akii was rapidly catching up with the leaders. By the halfway mark Hemery (timed at 22.8 sees), American Ralph Mann (23 sees), and Ugandan Akii (23 sees) were at world record pace.

Both 'Akii and the American looked poised to challenge Hemery's lead. The killer pace Hemery had imposed was beginning to take its toll, forcing him to slow down in the curve.

After the halfway mark, Akii began to take the lead, although still not apparent since he was running in the inner lane. He hit the sixth hurdle but recovered in good time to stay in contention. At the final curve, John Akii-Bua was clearly in the lead.

The "flying policeman" was in a class of his own as he negotiated the last two hurdles to power through to the finish.

His time: an astonishing 47.82 seconds, a world record, with Mann coming in for silver at 48.51 sees and Hemery bronze at 48.52secs.

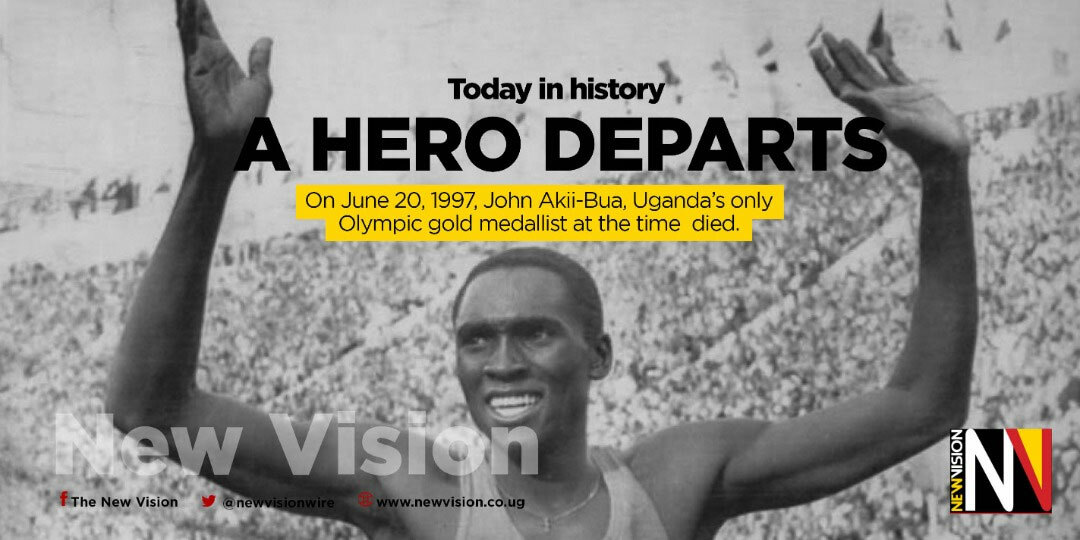

For the first time in Olympic history, a Ugandan had won gold.

The world was stunned: Akii had won with nearly six metres to spare and moreover had shattered the world mark by three-tenths of a second without the advantage of altitude.

Hemery's world record of 48.12 sees had come while running in the thin air of Mexico City at the 1968 Olympics. Akii's was the first-ever sub-48 seconds in the event.

The idea that an African might have any sort of success in an event demanding the technique, discipline, strength, and speed of the 400 metre hurdles was almost fanciful in a country where there were only grass tracks.

The record stood for four years, till Edwin Moses came along to shatter it with a 47.64 sees effort at the Montreal Olympics to signal a new era.

The Ugandan track legend missed a chance to defend his title when Uganda, alongside many African countries, boycotted the games as they protested apartheid in South Africa. It was a miss Akii regretted up to his death.

With 1973 and 1975 personal bests of 48.49secs and 48.49secs and 48.67secs in the hurdles, respectively; and a personal best of 45.82secs in the 400metres flat just before the 1976 Olympics, Akii was the man to challenge at the 400metre hurdles in Montreal. The versatile hurdler attempted a comeback in 1980 at the Moscow Olympic Games, but he was only able to finish seventh in his semi-final. His reign as King of the low hurdles was over.

Born December 3, 1949, Akii was one of 43 children, from one father and eight mothers. Akii's father, who passed away in 1965, was a chief. One of his elder brothers, Lawrence Ogwang, finished sixth in the triple jump at the 1954 Commonwealth Games. There were others too, who engaged in different sports.

Following his father's death, Akii dropped out of school and joined the Uganda Police in 1967. By the time of his death, he held the rank of senior superintendent, awarded to him by President Idi Amin. Following Akii's spectacular performance at the Olympics, Amin, a sports enthusiast, changed Stanley Road in Kampala to Akii-Bua Road.

As the excitement over the gold medal fizzled out, however, Amin's attitude towards Akii also changed. Akii happened to come from the same Langi tribe as Dr. Apollo Milton Obote, who Amin had overthrown.

After missing the 1976 Olympics, Akii was reportedly placed under house arrest by Amin, the same man who had named a street and a stadium after him and even given him a house and a car.

Akii once said all he could do was stay at home and listen to Diana Ross records.

When he tried to take his wife and three children out of the country for athletics competitions he was stopped.

The crisis deepened in 1979 when Tanzanian troops moved on Kampala; Akii fled with his family to Kenya.

Puma, the German company whose shoes he wore on the golden run, came to his aid, and he and his family were whisked to Germany.

On a trip back to his home, he found that looters had vandalized his house and his Olympic medal had gone. There are actually several conflicting stories on how Akii lost his gold medal. One of them is that he donated it to a Greek boy, who was training hard to be like Akii.

After years in exile, Akii returned in 1987 to embark on a coaching career. But although he handled several youths, including this writer, none went far in his footsteps.

Apparently, wonderful athletes don't automatically metamorphose into wonderful coaches.

The track legend passed away on June 22, 1997, at Mulago hospital, at the age of 47. Already a widower, he was survived by 11 children.

Uganda's only Olympic gold medalist was accorded a state funeral, followed by a colorful burial at his ancestral home in Lira.