Remembering Akii Bua: Forever gold

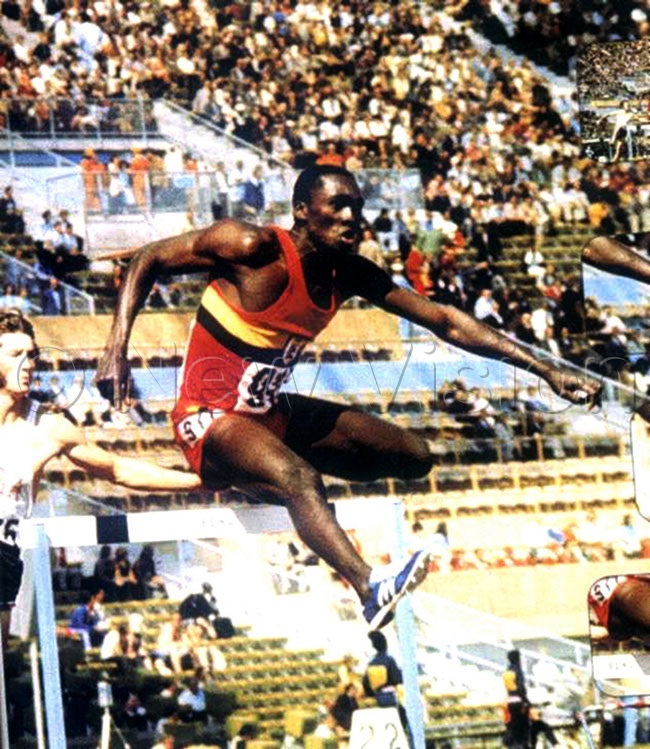

Forty seven years ago almost to this day, John Akii-Bua earned Uganda recognition by winning Olympic gold in the 400m hurdles in Munich, Germany.

Face of gold

By Kenneth Andrew Matovu

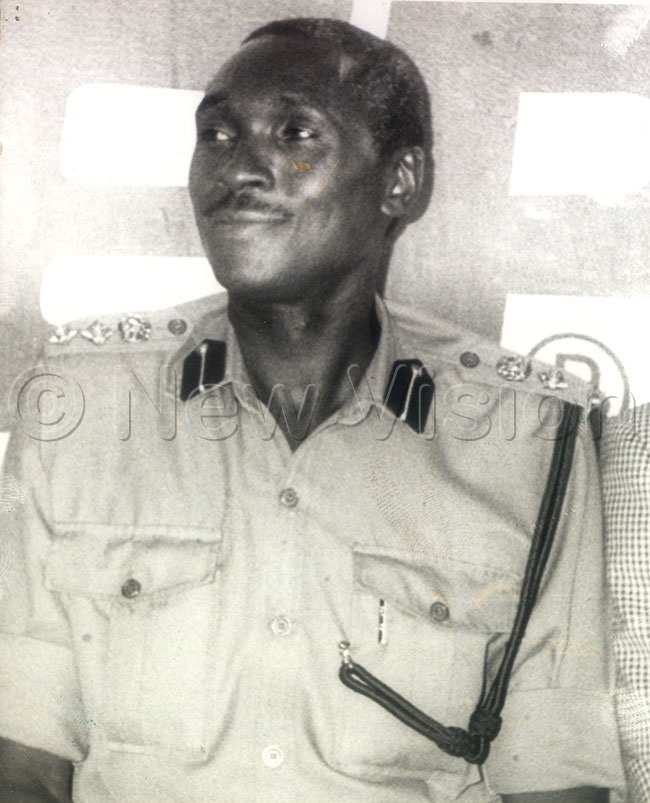

The zenith of Uganda's sporting history is John Akii-Bua's gold medal at the Olympic Games in Munich, Germany in 1972. Then a 24-year-old police officer, Akii captured the imagination of the world when he won medal in the 400 meters hurdles in a world record time of 47.82 seconds.

There were rave reviews about the athlete's performance from all the major local and world media. The feat even took on political proportions with the then Ugandan president, Idi Amin Dada exploiting it to boost the image of his despotic regime.

At his tender age, Akii was destined to be a pointer to the future of athletics in Uganda. The hurdler inspired many youngsters over the next couple of decades.

Akii's win came during an economic war. Amin had just expelled Asians from Uganda after blaming them for the dwindling economic situation in the country. Akii's world record helped focus the international attention on Uganda from disdain to glory.

Perhaps the most significant fact is that Akii's victory remains Uganda biggest success at the Olympics. Eridadi Mukwanga (Mexico City 1968), Leo Rwatawogo (Munich 1972) and John Mugabi (Moscow 1980), all boxers, won silver medals for Uganda. Bronze medals have come from Rwabwogo (Mexico City), Faisal Musante, also a boxer (Munich), and 400m sprinter Davis Kamoga (Atlanta 1996). There have been other great performances by teams and individuals. Cornelius Boza-Edwards, John Mugabi and Ayub Kalule have been world boxing champions and chess player Geoffrey Makumbi won a gold medal at the chess Olympiad in America in 1996. The national soccer team — the Uganda Cranes — reached the final of the Africa Cup of Nations in 1978, and SC Villa, Simba and KCC clubs have each once won regional honours. But Akii's display was the acme and, no doubt, provided the greatest spectacle for all of the nation's media. The event, thus, easily became the focal point of this research.

This paper delves into how the media reacted to Akii-Bua's performance at his time of glory as well as the media's coverage of the build-up to the feat. Here is a brief history of media coverage of sports before Akii's big day and a detailed report of how coverage has been handled since.

Akii-Bua's rise to glory

When the International Amateur Athletics Federation (IAAF) issued a list of the 100 best athletes of all time in 1993, Uganda's John Akii-Bua was one of only five Africans on it. The other four were Kipchoge Keino (Kenya), Hassiba Boulmerka (Algeria), Abebe Bikila (Ethiopia) and Said Aouita (Morocco).

The late Akii-Bua was not mentioned for nothing. In winning the gold, he smashed the world record then lowered it from 48.41 to 47.82, thus becoming the first man to cover the distance in a sub-48 time.

Then President Idi Amin rewarded Akii for bringing home Uganda's first Olympic gold medal, by naming a Kampala road and a Gulu stadium after him. He also gave the athlete a house and car, besides promoting him in the police force to the rank of assistant inspector.

Not to be outdone, the commercial world sought to cash in on the Ugandan's popularity. The German sportswear manufacturer, Puma, signed a contract with him-to help them advertise their products.

Akii was born in Lira in December 1948 to Abako county chief, Yusuf Lusepu Bua. He attended Abako Primary School and Aloi Ongom Secondary school in Aloi County. Akii, however, dropped out of Aloi when his father died because he had no-one to pay his school fees. Helpless, Akii joined the police force.

At Nsambya Police Training School, where physical education and Sports were compulsory, his talent, which had gone almost unnoticed during his school days, started to blossom.

He passed out in 1967and got posted to Nsambya, Masaka, Mpigi and Buwama before returning to Kampala. Records show it was police coach Jerome Ochama who encouraged AKii to take up athletics seriously.

Although he had proved his worth in other athletic events, after the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh, Scotland, Ochama advised Akii to embark on specialized systematic training in athletics.

The young athlete's chances brightened with the arrival of Malcolm Arnold, a coach from Wales. Arnold was contracted to coach the national team and in just weeks had already spotted Akii's potential. A short while later, the coach had worked it out that the Ugandan was tailor-made for hurdles.

Akii's preparations for the Munich campaign began early 1971 when he gauged his performance against world record holder David Hemery of Britain on the latter's home turf. Weeks later, at Wankulukuku Stadium, he became the first African to run the 400m hurdles under 50.00.

The time was hotly disputed by John Valzian, a white coach attached to Kenya, who was then handling Akii's regional rival, the Kenyan hurdler Billy Koskei. The Ugandan had beaten Koskei in the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh in 1970.

A chance to silence the doubting Thomases came Akii's way few weeks later during the United States rest of the world duel in June 1971 in California. Arnold, respected around the world, used his influence to get Akii an invitation.

The coach smiled all the way as his brilliant charge won the 400m hurdles easily in 50.20 before anchoring the rest of the world's 400m flat relay team to victory. He was not done. The following month, there was an inauguration competition between Germany, the USA and the Pan African team in North Carolina, USA and this time, to less surprise, Akii won in an even better time of 49.00.

The latest victory meant it was no longer necessary for Arnold to get him invitations to meets across the World - the athlete's name had become good enough.

Myth has it - for he was raised to mythical status - that, before departing for Munich, Akii did a total of 800km of cross country running in addition to jogging and weight training. Arnold's ultimate ambition was to see Akii break Hemery's record of 48.01 and this Ugandan did at a practice session. However the optimistic tactician kept it secret.

When the September games came, Akii was at his awesome best. He went through the elimination rounds without breaking a sweat. In the semi-finals, however, he hit a hurdle and got a deep cut on the left knee. The same day, he had a tooth extracted, which led to a swollen cheek.

Tension was high in the Ugandan camp on the day before the finals. The team doctor, John Ntege, feared to have the cut stitched, in fear of weakening Akii. The previous night, the athlete had refused to talk to anyone and even rejected food, preferring to concentrate on the final. Before going to the blocks, Coach Arnold told him to remember hurdle number five. There, he instructed the student to change his stride pattern from the left leg to the right.

Though he was in a disadvantageous lane, he run fastest to clock 47.82 seconds, setting a new world mark. In the second place was Ralph Mann of the USA (48.51secs). Hemery was third in 48.52secs, while fourth was Joe Seymour of the USA in 48.64secs.

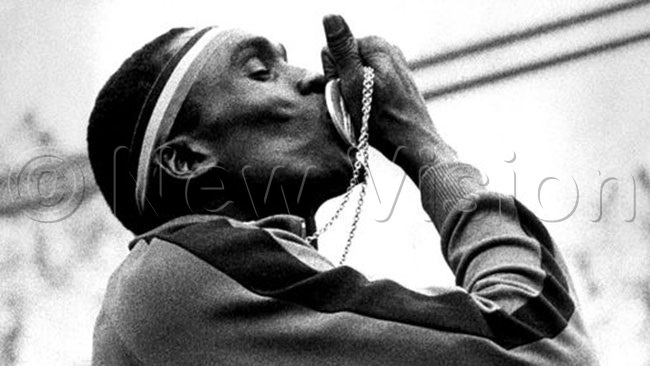

The joy among Ugandans in the stadium was beyond description as Akii leapt over a couple more hurdles on his victory lap.

Dr. Ntege says American scientists, so impressed by Akii's build and technique, decided to model an athlete of their own on the Ugandan's "vital statistics".

And the Americans were to have the last word in the battle of wits — not that it was any fault of Akii's. The Ugandan had continued to be the hottest hurdler in the world for the next four years and when the next Olympiad, in Montreal, Canada, in 1976 came round, he was the favorite to win his race.

Then, what does a New Zealand rugby team go and do? It took part in a competition in South Africa, a country that was under world sanctions for practicing apartheid?

Several countries, including Uganda, threatened to boycott the games if New Zealand took part. The Kiwis remained adamant and the threats increased, culminating in Amin withdraw¬ing the Ugandan team. The athletes had already arrived in Canada, though.

Akii was, thus, unable to defend his title and, with Dr Ntege in tow, watched on television in a London pub as his imitation, American Edwin Moses broke his record with 47.64secs.

The miss diminished any chance Akii might have had of getting Uganda another gold medal. When he returned to the games 1980 in Moscow, he was 29 and clearly past his best. Consequently, he even failed to make it to the final.

The anti-climactic performance in Moscow marked the end of Akii's career who then became an official of the Uganda Amateur Athletics Federation. With the passing years, Akii's worldwide popularity declined.

Moses continued to dominate the hurdles, running an incredible 164 races without defeat. Meanwhile, Akii held on to endorsements from Puma, but even those ran out in the mid-1980s leaving him to hold onto the last icons he had — the medal, the car, the house, a street and a stadium — in the life of an ordinary cop.

The national hero was unhappy. When the excitement about his success faded, the officials at the UAAF saw him as a stumbling block to their ambitions of staying in power for as long as they wished.

Akii was a constant critic blaming them for the fall in athletic standards in the country. Eventually, he was phased out of the hierarchy and stripped of his automatic entry to the UAAF general assembly as a national hero.

The scenario led to Akii's quitting UAAF in 1996.

"In sports in general there is a feeling of keeping others out of management," Akii said during an interview in December 1996. "There is no working together. They even put it in the constitution to block people".

The gold medalist charged that the officials did not care about sports, taut money.

"There are people who go for monetary gains," he said. "Because of democracy, it is very difficult to remove such people. They spend little and get back much."

In 1996, prior to the UAAF general assembly, Akii was told that, to make it to the assembly as a delegate, he had to stand for election in his hometown of Lira.

"I do not think it was proper for me to go to Lira and come from there," he said. "I would have qualified automatically as an Olympian, In the elections, I went in as a police representative but was shut out.

"The UAAF constitution does not provide for famous people. There is no role model for athletes; nobody is used to inspire these people. We are sitting tools not used by the association."

Akii, who had lost his wife a few months previously, was never used again. In early 1997 he fell ill. He was frequently bed-ridden and looked increasingly emaciated. His morale was running at its lowest ebb, Akii died on June 10, 1997.

Close friends say he had been circumcised — he also wore a tarbush (Islamic head dress) in apparent conversion to Islam. That, perhaps, is where he sought the happiness he could not find in his medal.

This is an extract from a research project by the late Kenneth Andrew Matovu while he was a student at the Makerere university mass communication dept.