When Stephen Kiprotich stunned the world

The ever smiling runner was on a few peoples’ radar because he was a relatively newcomer on the big stage.

ATHLETICS

Long before the curtain fell on the London 2012 Olympics, many had written off Uganda as having concluded yet another outing without a medal.

This was quite understandable. Big names on Team Uganda like Moses Kipsiro and Dorcus Inzikuru had all left empty-handed.

Then, it had also been 16 years since Davis Kamoga had won Uganda's last medal - a bronze at the Atlanta 1996 Games. So sporadic and far between were Uganda's Olympic medals, that Kamoga's bronze had equally come 16 years after boxer John Mugabi's silver in Moscow.

Was it therefore surprising that Uganda's sports minister and leader of delegation in London Charles Bakkabulindi had hurriedly left London long before the last events?

"There is no hope. We were tourists," a team official stated after Kipsiro finished tenth in the 10,000 meters.

But there were still those with hope. Yours truly was amongst these few who felt Uganda still had an ace up its sleeve. Talk of a last-ditch attempt. This group was looking at the very last event of the games, the men's marathon.

And the man on whose shoulders this huge responsibility fell was none other than Uganda's lone ranger in the 42 kilometers event - Stephen Kiprotich.

The ever-smiling runner was on a few peoples' radar because he was a relatively newcomer on the big stage. That he also arrived in London well into the games when all hope seemed lost, also did not help in having him on many a Ugandan's thoughts.

Like most elite marathon runners, he had kept in his camp in Kapkoros, western Kenya to make the best of high altitude training. What did not draw many peoples' attention was the steady progression in Kiprotich's career.

In 2011, a year before the Olympics, he had entered the Enschede Marathon in the Netherlands as a pace maker, but after going for 30 kilometers in the lead, he decided to hold on and won the race in a new course record.

Then, he had the same year finished ninth in the World Championship marathon in Daegu, South Korea. He made the London Olympics team after finishing third in the prestigious Tokyo marathon, a member of the World Marathon Majors.

So, for those who cared to follow Kiprotich's buildup to London, he was no lightweight.

'A very good spot to break away'

On the eve on the marathon at the London Olympics, Kiprotich and his coach Gordon Ahimbisibwe tried out the route.

When they got to the 37km point along London's Embarkment and Birdcage Walk, Kiprotich surprised his coach when he suddenly said "this is a good spot to break away".

Ahimbisibwe, who also couldn't imagine Kiprotich winning, just smiled and also acknowledged that indeed it was a good point for whoever would be in the lead at that point. Deep down within him, he knew that leader certainly wouldn't be Kiprotich.

Later that evening and on the morning of the marathon, Kiprotich was given a thorough massage by team physiotherapist Alex Leku.

"My body and mind were relaxed. I must say he did a good job."

On the bus to the marathon starting area, Kiprotich was restless. "I kept having this feeling that something big was about to happen, but I couldn't tell exactly what it was," he said hours later.

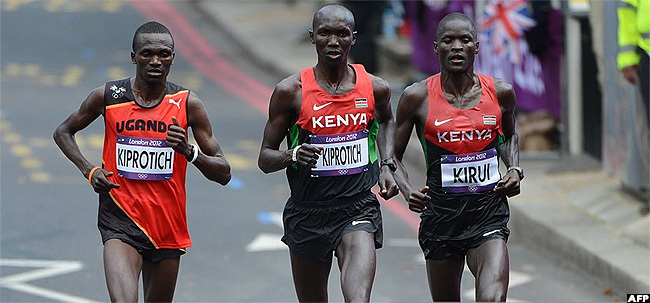

When the race began, the spotlight was unsurprisingly on Kenyans Wilson Kipsang and Abel Kirui. Kipsang, whose vest interestingly also bore the name Kiprotich, was the reigning London marathon champion while Kirui was the world champion.

Then, of course, there were also the revered Ethiopians, who, together with the Kenyans, had dominated the Olympic medal podium in this grueling event.

Another fact that ruled out Kiprotich from the bookmakers favourites was the big names' times.

These were 2:03hr runners compared to Kiprotich's 2:07 personal best. But Kiprotich was not about to be intimidated and he kept on the heels of the lead pack for most of the opening kilometers.

Kipsang then made an early move to try to break up the lead group, building a 21-second lead at one point.

It was a high-risk strategy in such warm conditions, though, and he paid for it as the race went on as he started to look less and less comfortable. He missed a drinks stop and by the 25km mark, his advantage was down to seven seconds.

Kirui and Kiprotich soon joined the leader to make it a three-way battle for the gold medal.

At the very spot that Kiprotich had the previous day shown his coach as an opportune point to break away, something dramatic happened.

He first seemed to be starting to struggle, holding the back of his leg, but he suddenly produced a big surge, leapt to the front and pulled away.

Kirui just can't forget that moment. "I saw him [Kiprotich] coming like a cheetah. It was very hard to control that kind of move."

And in front of packed crowds rows deep all along the looped central London course, the Ugandan, who moved to Kenya as a teenager to train, started smiling and pointing his finger into the air as he closed in on victory, before draping himself in the Ugandan flag as he crossed the line.

Kiprotich followed in the footsteps of his compatriot John Akii-Bua, who was a 400 metres hurdles champion 40 years earlier, and crossed the line in two hours, eight minutes and one second.

With billions worldwide following the marathon that hot afternoon, Kiprotich had been thrust from obscurity to stardom.

He had, despite all doubts, also got the last laugh.