Contemporary Uganda as seen by an insider East African 'mzungu'

Jul 29, 2019

An idealist, Pike believed that liberal policies, in as far as they affected the media and national politics, could never be rolled back.

OPINION

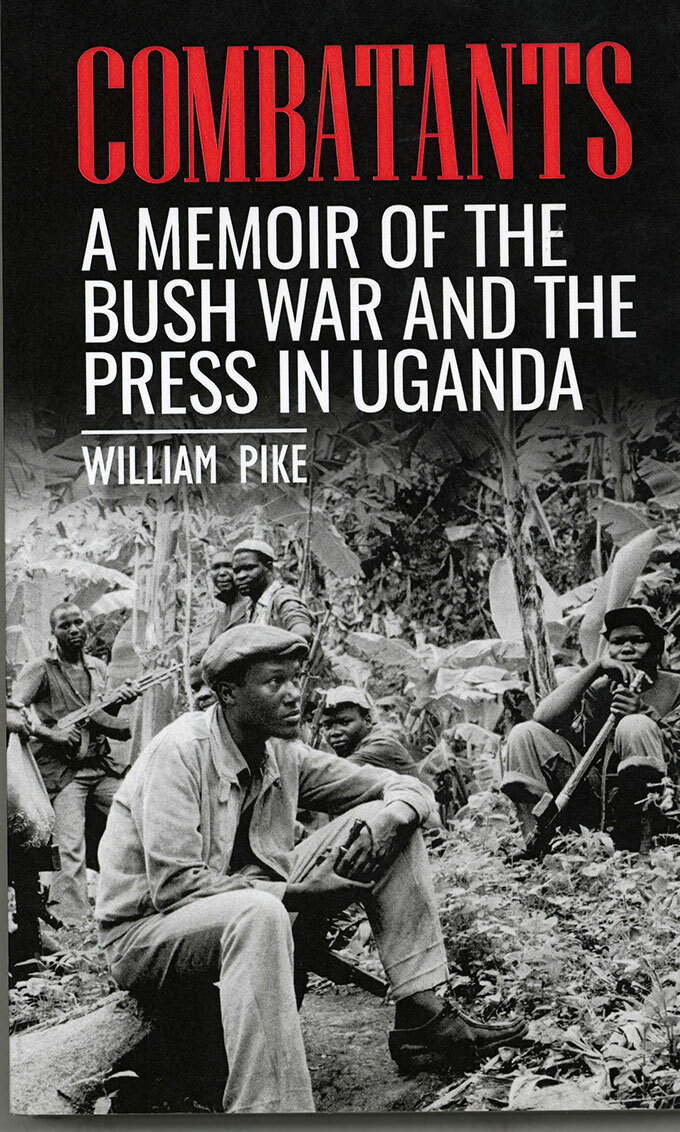

Combatants: A Memoir of the Bush War and the Press in Uganda

By William Pike

Self-published, 2019

294 pages

Available: Aristoc Booklex; Uganda Bookshop; Amazon (Kindle & paperback)

Reviewer: David Sseppuuya

Not many can claim to be well-rounded East Africans. As one, William Pike is rivaled possibly only by Angelina Wapakhabulo, the Tanzanian-born former Uganda ambassador to Kenya.

Pike, born in Tanganyika (pre-Independence Tanzania), making his name (while also taking up citizenship) in Uganda, and establishing himself in business in Kenya, is as rounded as they come, and he brings this background into what will be a valued record of the intermediary stage of Uganda's post-Independence history.

Malcolm X, the US civil rights activist, said that "it takes heart to be a guerrilla warrior because you are on your own".

That, in a sense, is Pike's story: he started out on his own in 1984, alone and occasionally frightened, to bring the story of the guerrillas of the National Resistance Army to the world, ending up on his own, proud of his role in Uganda's revolution but slightly disillusioned when the relationship with a now-twitchy NRM came to an end in 2006.

This breathlessly flowing narrative, focusing principally on the resistance war in the jungles of the Luweero Triangle - reference to "being in/going to the bush" will resonate with his Ugandan readers, but lose the British audience, the secondary one - and the early years of the Museveni administration, is a three-dimensional tale:

Being a Briton lends the book a bird's eye view that a local writer would not have; as a journalist, he has the vantage point of a fly-on-the-wall observer of society; his connections with the NRM, contesting for and then exercising power, makes Pike an inside-lane runner alongside members of what could be described as a now-decimated faction (Eriya Kategaya, Mugisha Muntu, Bidandi Ssali, John Nagenda, Amanya Mushega) of NRM's progressive wing.

This book will serve as a record of how the early years of NRM was a period of strong convictions and revolutionary drive, regulated by the politics of consensus and the preeminence of social and economic benefit before political expedience took over.

An idealist, Pike believed that liberal policies, in as far as they affected the media and national politics, could never be rolled back. Alas, it was all to come to a juddering halt in (election year) 2006, an episode he handles in the final section of the book with brutal honesty, but eminent fairness.

His journalistic attention to detail, and record-keeping borne of copious note-taking and journaling, brings up anecdotes that an armchair historian would be hard-pressed to record: "women chanting softly….their arms rippling sinuously"; Vice President Paulo Muwanga's quip that "emagombe tejjula (graves can never be filled)"; Prof Yusuf Lule's desperate plea to know whether the NRM that he chaired from exile in London does talk about him in the bush; President Museveni's momentary lack of composure in the hours after learning that Banyarwanda officers had deserted the NRA and invaded Rwanda on October 1, 1990.

Pike brings a refreshing honesty to his analysis of the Uganda of the NRM. He is respectful, even admiring, of Museveni, but does not shy away from making critical observations: "Some of Uganda's problems today are of Museveni's own making, but others are the unavoidable and deeply complex problems of any developing country". It is this philosophy that he used in building The New Vision into a respectable public institution, an ideology that informed the paper's editorial policy: support the principles of the NRM but not its failures.

He tells the story of The New Vision, front-page stuff for how to run a state-owned (later partially-privatized) enterprise. Credibility was established through big investigative stories. With an evolving cadre of professionals, a meritocracy was built, competitive in the market, respectful of the country, and run on sound management and business principles. It could have been a microcosm of Uganda.

In that story, he is a little hard on James Tumusiime, his deputy in the early years with whom they clashed variously; it is, though, such candour that makes ‘Combatants' such a compelling read.

It is also the story, to a lesser extent, of a pivotal time for the media in Uganda, transitioning from the statist 1970s and ‘80s to a liberalised dispensation, of which he was a critical player.

The narrative retains a singular ability to coalesce situations into simple ideas: Oyite Ojok being not a soldier, but a warlord; Uganda's relative poverty being encapsulated in the 1991 per capita health budget of 3.5 dollars a year during the AIDS epidemic; the "intellectual and political gulf" between Museveni and Kenyan President Daniel Arap Moi.

As someone who walked the jungles of Luwero in search of a breakthrough story, walked the corridors of power in the balancing act of editorship and walked the road of capitalist enterprise, fraught with dangers in a corrupt business environment, William Pike has seen and recorded the lot.

Few would have predicted, though, that the Pike-NRM love-in would all end in tears. It did, in the final months of 2006 as he made his exit, with this reviewer, his long-time deputy, and putative successor, being unwitting collateral damage. Left on his own, honest and yet fair, Pike handles this final episode with dignity, professing even relief at finally departing.

There are a few minor quibbles: referring to Oyite Ojok as an Acholi, yet he was Langi and as Army Commander when he was Chief of Staff; or reference to NRA's first commander as Comrade Ssepuya, yet he was Seguya.

The biggest gap, however, remains the mid-1990s to the early 2000s. Little is said of this period during which both Pike and The New Vision were major players on the national scene.

These latter years, especially the political move to adjust the Constitution to allow for the lifting of presidential term limits, are handled peripherally, mainly in as much as they influenced Pike's eventual departure from The New Vision. It remains material for an updated edition.

None of this should detract from an excellent addition to Uganda's contemporary political history, keen on detail and sharp on historical fact without being over-elaborate. Its style draws the reader into, and carries them along, a story that will be told for generations.

Extensive illustration with photographs and qualification of historical events with direct quotes and reported speech will serve to protect this phase of history against revisionism, which could conceivably be the biggest long term benefit ‘Combatants' will bring to Uganda.

A final quibble: the Dramatis Personae at the backend, listing bios of key characters in the narrative, welcome though it is, is no substitute for an index, which would be a critical feature for a book that will serve as a historical reference to key moments in our national story.

David Sseppuuya served as Deputy Editor-in-chief to William Pike at The New Vision from 1999 to 2005, and as Editor-in-chief, 2005-2006, when Pike was Chief Executive. dsseppuuya@yahoo.com