Karamoja miners work on empty stomachs

Every day, for eight to 10 hours, local miners endure extreme exploitation at the hands of mining companies.

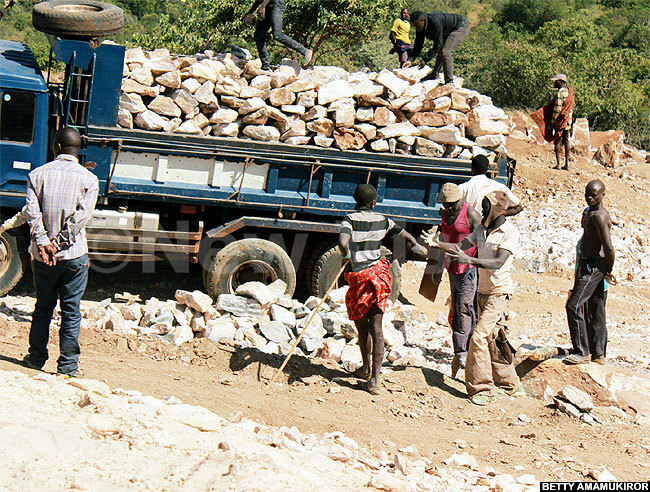

PIC: Residents cracking stone boulders at the Kosiroi mining site. (Credit: Betty Amamukirori)

MINING SECTOR

In Karamoja, miners endure abuse as companies ferry minerals out of the region. Men and women take alcohol for lunch and are paid peanuts, while children work without pay. New Vision's Betty Amamukirori interacted with several miners and employers

The cattle, sheep and goats grazing freely on the mountain slopes, give an impression of a beautiful, peaceful and secure region. Its richness in minerals such as gold, limestone and marble is an icing on its beauty. However, at the bottom of this allure is a totally different picture characterised by despair, hopelessness and helplessness.

Every day, for eight to 10 hours, local miners endure extreme exploitation at the hands of mining companies. Mining in Karamoja is still done on a small scale. In what the local authorities describe as speculation, companies come and go.

In Moroto district, Jan Mangal and DAO Marble came and left after reportedly running bankrupt, leaving Tororo Cement as the only established mining company.

The mining areas in the district are in Rupa, Katikekile and Tapac sub-counties. In Rupa, there is small scale gold mining, while marble stones are only mined in Rata village, which forms the border between Rupa and Katikekile. In Kosiroi village, Tapac sub-county in Moroto district, women, men and children spend over 10 hours a day, cracking stone boulders, with no food and sometimes water.

When hunger bites, they take the local brew or sachet waragi to calm it. For 15 years, Tororo Cement has been getting limestones and marble from this village. Every day, heavy duty trucks ferry these minerals from the site to Tororo district, where the limestone is used in the manufacturing of cement, while the marble stones are used for making tiles and utensils.

The Tororo mining site covers about 5.5 sqkm. Before these trucks are loaded with the stones, people used to crack stone boulders. For the hard boulders, they use fire to soften them before the splitting is done.

When all is broken into small, carriageable pieces, these rocks are then loaded onto waiting trucks for transportation.

Miners loading a truck in Kosiroi village. The are paid sh150,000 after loading

The cost

Charles Emokol, a chemist with Tororo Cement, who has been working closely with the miners, said people pay between sh150,000 and sh210,000, depending on the size of the truck.

A 10-wheeler truck carries between 30 and 35 tonnes of stone. A miner who fills it, gets sh210,000.

Life of miners

Michael Lotita, 18, one of the miners, says it takes him and a team of other three miners, whom he directly employs, five days to fill a sh150,000 truck with stones. He pays each of the employees sh7,000 per day.

"We work from morning to evening. When one is hungry, they take a sachet of waragi or local brew. There is no money for food. Even getting water is difficult. When the nearby borehole breaks down, we walk for 15km to get water. Here, a jerrycan of water costs sh2,000," he says.

Emokol backs this claim when he says the water is sometimes foul-tasting because of sodium chloride and that most of the boreholes in the area have broken down.

Lolita says when one of them gets an accident, they have to walk for about 15km to access medical help for which they have to pay for.

"When one of the boulders peeled the skin off my feet, I had to pay sh200,000 for treatment. I was lucky I had saved the money but people here depend on nature. The wounds heal on their own because people cannot afford treatment," he says.

Lotita, who has been in the mining business for the last three years, joined it with the hope of getting money to pay for his secondary education. But, he now fears that this dream may never come true.

"Whatever I get goes into paying my employees, I use the balance to buy food. Tororo Cement promised us scholarships, but nothing has ever been done," he says.

Surrounding him, is a group of other miners, most of them with visible scars. Some open their palms to expose the deep cuts caused by the stones. Hopping with one leg and with the support of a walking stick, Lodim Lokitare is bitter.

He lost his left leg after one of the stone boulders hit him.

"I looked for help, but no one came to my aid. I was here. The company officials were here but they could not help me. My father sold his cow. We raised the money, but it was too late. My leg had to be amputated," says Lokitare through a translator.

His leg was amputated at Matany Missionary Hospital in Napak district.

This is about a two-hours' drive from Moroto. When the wound healed, he had to return to the exploitation in the mines, not because he wanted but because he had no other alternative to earn a living.

"These people pay us little, but we have no option. We console ourselves with the little because at least I can buy food for my three children," he says.

In Kampala, a bag of cement costs between sh28,000 and sh30,000, depending on the location, while a square metre of tiles is sold between sh18,000 and sh31,000. The price also depends on the colour and quality. In Jinja, a tonne of marble is sold at sh120,000.

|

Other sites

The DAO Marble site in Rata village, Rupa sub-county, is a beehive of activity. Women, children and men are busy cracking stones, digging the soil and loading the trucks.

|

No accountability

He says there is no mechanism at the district to help them know how much the mining companies are ferrying out. He says when they tried to ask Uganda Revenue Authority to put a weigh bridge, a promise was made, but two years later, nothing has been done.

Edward Eko, the district principal assistant secretary, says due to the absence of a verification mechanism, the district does not know how much these companies pay in terms of royalties, but whatever they give the Government, the district receives 20%.

Ten percent of this remains at the district, 7% goes to the local government, while 3% is paid to the communities through existing trusts.

However, Nangiro says there have been disagreements in the communities on who should receive the 3%. So, the money has never been remitted. Communities have been asked to organise themselves in a way that all will benefit from the money.

Gerald Eneku, the mines inspector in Karamoja, says on top of the royalty, Tororo Cement pays sh7,500 per truck to the district, but the payment had to be stopped when the district, the community and the local government disagreed on who should be the rightful beneficiary.

However, the locals deny knowledge of such money. Emmanuel Lokii, the vice-chairperson of Rupa Community Development Trust, says the money has never been remitted to the trusts.

The 2014 Human Rights Watch report states that there is inadequate information and participation in decisionmaking and confusion as to how the communities would benefit from the extractive industries.

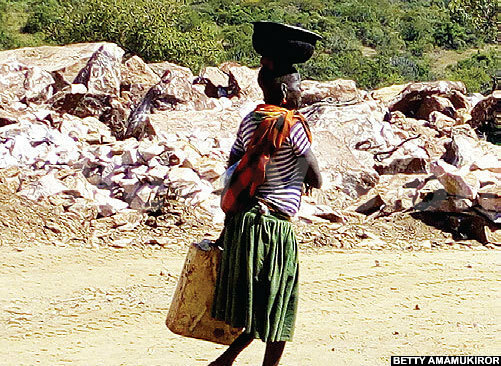

Women, men and children working at the marble site in Rata village, Rupa sub-county in Moroto district

Government compromised

Simon Peter Nangiro, the chairperson of Karamoja Miners Association, says the local authorities are compromised by these companies and the few who speak out against the abuse are threatened, intimidated and sometimes replaced by those willing to turn a blind eye to the exploitation.

He says some of their legislators were sidelined for being vocal on the abuses in the mines.

"We run into problems when government officials back these companies. This attachment makes the companies dictate to local governments what and what not to do. When we question why they overlook local authorities, we are accused of sabotaging investment," Nangiro says.

The hopelessness is further expressed by the district principal assistant secretary, Edward Eko, who admits that they cannot do anything to stop the exploitation.

"We are intimidated. There are many players in this business at various levels. We are dealing with a powerful government," he says.

Eko says one time he faced the wrath of these players when he tried to stop Tororo Cement from taking the limestone and marble without increasing the pay to the local miners.

"It did not go well with some of us. The company has many shareholders who are highly connected. We were threatened and I had to go into exile for three years," Eko says.

Empty promises

Emmanuel Lokii, the vice-chairperson of Rupa Community Development Trust and who is also the district youth councillor, says when DAO Marble and Jan Mangal entered Karamoja, they promised to build schools, give the local children scholarships, give the locals jobs and build hospitals.

However, Egyptians were brought to work in the mines and none of the promises were fulfilled.

"The few locals who got employed were never paid when the company closed due to bankruptcy. We counted our losses and we are now doing the mining on a small scale," he says.

Apalokol Lokiru, a resident of Kosiroi village, says in the three years he has been mining, he only saw the Tororo Mobile Clinic once and has never seen it again. When asked to explain, Charles Emokol, a chemist with Tororo Cement, says they found the land vacant with most of the people living on the mountains.

So, they could not put in place the social services.

However, Eko notes that Tororo Cement has been able to build an access road and one school in the community.

Gerald Eneku, the mines inspector in Karamoja, explains that Tororo Cement is the only company that has given something to the district, but companies such as Jan Mangal Uganda Limited exited the district without paying royalties, salary for the workers and surface rights.

Similarly, he says, DAO Marble exited Rata village without paying billions of shillings it owed the local employees, the hotels where the Egyptians were staying and the construction company that set up the structures at the site.

Eneku adds that dfcu and a local television station also made losses when the company failed to pay the loan and for the advertising time, respectively.

The two sites are currently being guarded by the army, even when the two companies are long gone. The companies could not be traced for a comment because they had ceased operations in the area.

|

Employers speak out

|

Limitations of the law

Edward Eko, the Moroto district principal assistant secretary, says their involvement in the mining sector is limited by the laws and policies that govern the trade.

He says the law gives powers to the central government and during major decision-making processes regarding the region's minerals, they are sidelined.

Gerald Eneku, the mines inspector in Karamoja, says the district only gets involved when the companies seek surface rights for mining. The rest of the processes are done by the energy ministry.

While the law on mining is currently under review, the local authorities hope that it would give them more powers to make decisions that can better the working conditions of local communities.

On the other hand, whereas the locals want better pay, better working conditions and provision of social services, they fear to press hard lest they get replaced with machines.