Data tracking changing Uganda's health care

Currently in Amolatar, one mid-wife has been indefinitely suspended as a result of the reports filed on her through the system.

PIC: A sign post of Amlator Health Centre IV. ( Credit: Jacky Achan)

HEALTH

AMOLATAR - It’s a sunny Tuesday afternoon; Sarah Aduku is seated under a tree at the Amolatar District Health Center IV holding her baby.

She brought her child to be immunised and is resting a little before they can begin the journey back home.

Curious, I ask if she has been attended to and her answer is yes. “How about the state of services?” I probe further. Smiling back she says sometimes there is a delay.

Alex Ogwal the Deputy Health-Officer-Amolator. (Credit: Jacky Achan)

“We have to wait a little long sometimes and this takes hours. We start from the triage (which is the process of determining the priority of patients' treatments based on the severity of their condition), then go to the clinician, followed by registration then finally we go to the dispenser. But, nonetheless we get the services we come for,” she says.

Aduku paints a picture so different from that of the year 2012 in Amolator. The people of Amalator in 2012 rioted over late coming and poor service delivery by health workers.

Alex Ogwal, the Deputy Health Officer who was working with the district back then remembers the riots vividly.

“Patients would come to health centres by 7:00am but, it would clock 4:00pm without seeing any clinician and they would have to go back home very late, unattended to,” he said.

He says at a health centre II that is supposed to have nine medical staff during normal work hours, one would find 2-3 if lucky.

“Hard pressed, people stormed the office of the then Resident District Commissioner, demanding good health care. It was a tough time for the health workers,” Ogwal observed.

State of absenteeism

In 2009, the level of absenteeism by health care workers in Uganda was at about 52%, according to the Ministry of health.

The 2012/2013 Health Sector Performance Report also found that at least 40% of health workers countrywide were rarely at their workstations.

Whereas a 2015 study by IntraHealth International, revealed that 50% of health workers in Uganda’s public sector weren’t showing up, or were coming to work late but, left early to collect dual pay at another facility. District hospitals and lower health units were the most affected.

In Amolator, the Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) Pius Epaju says back in 2009, health workers did not view poor time management as a vice that would result into poor service delivery.

From a far, Amolator Health Centre IV. (Credit: Jakcy Achan)

At the time, medical workers were notoriously coming to work late and if they came early, they would not work on patients until later in the day.

So, in 2009, the integrated Human Resource Information System (iHRIS), an online open source monitoring system was introduced in Amolator and eight other districts to track attendance at work.

The system beyond recording work attendance also captures bio data and professional records of the health workers (Human Resource Information) and duty roster.

But, there was a problem. All that the iHRIS managers had done, was buy a computer, install the system and put it in the district Human Resource office.

Soon came numerous reports of computer breakdowns that needed our attention from Kampala, according to Denis Kibye, an informatics developer at IntraHealth International in charge of the system.

In attempt to improve the situation, Amolator just like the other pilot district had their internet provision paid, for a whole year.

But, it was misused for other activities and exhausted without serving its purposes, Kibye disclosed.

Eventually, in 2015, IntraHealth bought a central server and moved the system to the ministry of health headquarters, where districts focal persons accessed it anytime, without internet connection.

The iHRIS system has since been stable and greatly improved human resource management and provision of health care in the districts.

Tracking attendance

To use the iHRIS tracking system, health facilities track attendance of personnel on a daily basis by manually recording attendance, according to Alex Gwom the iHRIS focal person in Amolator.

Each member of staff who walks into the health centre records their name in a book, time of arrival and departure and appends their signature.

This manual data is then submitted monthly to the central iHRIS database, where data is computerized and individual health worker records are updated.

Once the monthly data is in, payroll managers in each district run attendance reports.

Sister Salome Adero who is in charge of collecting data at the Amolator District Health Center IV.(Credit: Jacky Achan)

They immediately see who reported to work for fewer days than the standard number of days required per month, usually 20.

They also check with facility heads to see if there are justifying circumstances for absenteeism, before recommending sanctions on them to the District Health Officer and CAO, who oversee public health facilities and funds.

Dr Jimmy Odongo in charge of Amolator District health centre IV says with iHRIS, medical staffs are waking up.

“Now they do not just disappear from duty because they know the consequences. If they must be away they inform those in charge,” he says.

Consolidating the system

The Regional Human Resource Officer Northern Uganda, Peter Alani says to boost iHRIS results the district also introduced performance targets to work with it.

Besides tracking attendance, medical staffs at the beginning of a financial year also have to set their own performance targets.

“If you are a midwife, you could commit to handling 1000 deliveries of babies in a year. But we encourage them to set realistic targets. If you seem to be falling behind, we give you room to explain why through quarterly reviews so you can still excel,” he says.

There are rewards too for those who excel at the end of the year. They have been given certificates of recognition and are applauded during meetings on the recommendation of the reward and sanctions committee in the district.

But, there are sanctions too in place to deter bad work behaviour. These include paying salaries based on the number of days one was absent, disciplining chronically absent staff, and removing ghost workers/individuals, who never report to duty, from district payrolls.

Currently in Amolatar, one mid-wife has been indefinitely suspended as a result of the reports filed on her through the system.

The reports indicated she was a non-team player who absented herself from work, harassed expectant mothers and served numerous suspensions.

“We kept transferring her from one health center to another, even taking her to a smaller one in the hope that the work load would not overwhelm her and she would change but had no success,” Ogwal says.

The mid-wife’s luck ran out a month ago when instead of offering care to four HIV positive mothers who had come for their ARV refill at the district Health Centre IV, she refused to attend to them and harassed and abused them, Ogwal reveals.

These cases of misconduct were captured in the system and when the district health authorities ran a check on her, the numerous negative reports were presented, warranting her indefinite suspension.

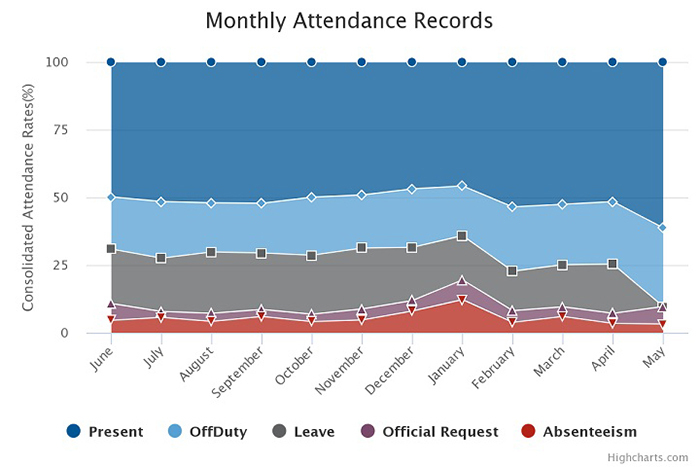

Amolatar latest attendance chat 2018

Other challenges faced

Despite the success obtained so far though, Gwom says taking records on paper and making it electronic has not been easy.

Sister Salome Adero who is in charge of the data collection at Amolator district Health Centre IV says the system can be time-consuming for late comers.

“When I remove the attendance books the late comers have to look for me which may still consume time that would otherwise be put in attending to patients,” she says.

Alani adds that there are also problems if data is not shared regularly. “If the senior management team does not demand for this iHRIS data on a regular basis for action it can be ignored and it won’t serve its purpose,” he explained.

The system is also manual. This exposes it to being compromised, because for example, one person might sign in for another to cover up for them.

It can also not be ignored that while the system helps with attendance and better service provision, it does not tackle major challenges the health workers face such as poor remuneration and work conditions.

Tony Opura who is in charge of Aputi Health Centre III says these conditions are the reasons some of health workers were absent from work in the first place.

“The health workers will not concentrate much on the job because of the need to do something to support their pay,” he says.

Dr Ebuku Ekwaru the Chairman of Uganda medical association says the system needs to work hand in hand with incentives.

“People may come for work because they know they are being monitored but may not be productive,” he explains.

Ekwaru says what has been proven to keep health workers on duty and actually working, are incentives that include good pay and a conducive work environment.

Dr Jimmy Odongo in charge of Amolator District health centre IV.(Credit: Jacky Achan)

Getting the result

Denis Kibye, an informatics developer at IntraHealth International, says they are now moving the attendance tracking module of iHRIS from using book records first, to using biometric machines.

Currently a team of IT and performance management experts from IntraHealth International and Ministry of Health are rolling out the biometric machines to capture all data electronically.

The biometric gadgets scans thumb prints of each and every medical worker and registers time of arrival and departure.

This eliminates any chance of a health worker signing in for a workmate as the finger prints are unique to each individual and demands that one is physically present to sign in or out.

So far all 14 regional referral hospitals in Uganda and 14 health centre IVs in Gombe, Adjumani, Kalanga and Katakwi have the biometric system installed.

Also the office of the Prime Minister is supporting the roll out of the biometric system to 37 district hospitals and health centre IVs in Eastern Uganda, while another 197 health centre IIIs and IIs in Eastern Uganda are getting mobile phones for automatic attendance registration once they get to work or when signing out of duty. The phones work same as the biometric machines.

Kibye explains the mobile phones unlike biometric systems do not heavily rely on the presence of electricity to operate which should make it efficient.

The iHRIS managers are also working on the system to serve members of the public so that they can log on to establish whether the doctor assigned to work on them is qualified and registered.

Presently iHRIS is installed in 24 countries in Africa, Asia, Central America and the Caribbean.

In Sierra Leone, using iHRIS the country’s Directorate of Human Resources for Health in early 2016 discovered 756 unverified health care workers out of 10,166 workers on its Ministry of Health payroll.

After review and reinstatements, 427 ghost healthcare workers and unsalaried staff, were permanently removed from the Ministry payroll, which saved approximately LRD 7 billion about (Shs200 billion).

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), payroll analysis showed that 27% of the health workers listed as salary recipients in the electronic payroll system were ghost workers, as were 42% of risk allowance recipients.

As a result, the Ministries of Public Health, Public Service, and Finance reallocated funds away from ghost workers to cover salaries and risk allowances

Ten years down the road, Uganda has had its share of success with the system which has boosted work attendance and importantly, good health care by medical staff.

Today Amolator is one of the districts in Uganda with the best medical personnel turn up at work and with improved health care.

The iHRIS monthly report put absenteeism in Amalotor at only 3.2% and at 11.2% nationwide as of May 2018.