Karl Marx 200 years on: five core ideas

A loot at five core ideas of the influential and highly divisive German thinker, on the 200th anniversary of Marx's birthday.

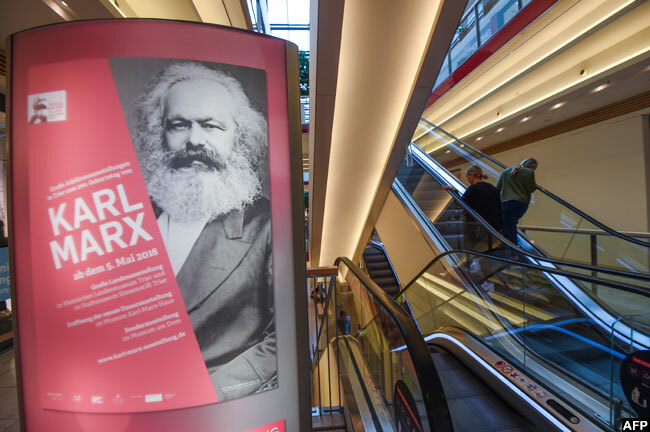

PIC: A man walks past boards displayed in Trier, southwestern Germany, as part of the celebrations marking 200 years of the birth of German philosopher Karl Marx. (AFP)

HISTORY | PHILOSOPHY

Karl Marx's work "can be explained in five minutes, five hours, in five years or in a half century," wrote French political thinker Raymond Aron.

A utopian vision of a just society for some, a blueprint for totalitarian regimes for others, Marxist thought is laid out in the Communist Manifesto and the three-volume Das Kapital.

Here are five core ideas of the influential and highly divisive German thinker, on the 200th anniversary of Marx's birthday.

'Class struggle'

"The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle," says the Communist Manifesto, co-written with Friedrich Engels and published in 1848.

Marx believed that humanity's core conflict rages between the ruling class, or bourgeoisie, that controls the means of production such as factories, farms and mines, and the working class, or proletariat, which is forced to sell their labour.

According to Marx, this conflict at the heart of capitalism -- of slaves against masters, serfs against landlords, workers against bosses -- would inevitably cause it to self-destruct, to be followed by socialism and eventually communism.

'Dictatorship of the proletariat'

This idea -- coined by early socialist revolutionary Joseph Weydemeyer and adopted by Marx and Engels -- refers to the goal of the working class gaining control of political power.

It is the stage of transition from capitalism to communism where the means of production pass from private to collective ownership while the state still exists.

The concept, including suppressing "counter-revolutionaries", was proclaimed by the Russian Bolsheviks in 1918.

Vladimir Lenin wrote that it is "won and maintained by the use of violence", signalling the authoritarian drift that began after Russia's 1917 October Revolution.

Communism

Marx and Engels wrote the "Manifesto of the Communist Party" in 1848, at a time of revolutionary turmoil in Europe.

It only reached a wide readership in 1872 but became part of the canon of the Soviet Bloc in the 20th century.

For Marx, the goal was the conquest of political power by workers, the abolition of private property, and the eventual establishment of a classless and stateless communist society.

According to Marx's theory of historical materialism, societies pass through six stages -- primitive communism, slave society, feudalism, capitalism, socialism and finally global, stateless communism.

In reality, the abolition of private property and the collectivisation of land resulted in millions of deaths, especially under Russia's Joseph Stalin and China's Mao Zedong.

'Internationalism'

"Workers of the world unite!" is the famous rallying cry that concludes the Manifesto and seeks to create a political structure that transcends national borders.

The idea lay at the heart of Soviet internationalism, uniting the destiny of countries as geographically distant as the USSR, Vietnam and Cuba, and revolutionary groups including the Colombian FARC or the Kurdish Workers' Party PKK, as well as anti-globalisation movements.

'Opium of the people'

Marx believed that religion, like a drug, helps the exploited to suppress their immediate pain and misery with pleasant illusions, to the benefit of their oppressors.

The quote usually paraphrased as "religion is the opium of the people" originates from the introduction of Marx's work "A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right".

In full, it reads: "Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people."

The idea was used to justify brutal purges of religions in Russia, China and across eastern Europe.

Some scholars point out that Marx saw religion as only one of many elements explaining the enslavement of the proletariat and may have been surprised to see radical atheism become a core tenet of communist regimes.