Cape Town water crisis: Some lessons for Uganda

Residents will be required to go to one of the 200 collection points to queue for a daily allocation of 25 litres

WATER SHORTAGE

By Dr. Eng. Kant Ateenyi Kanyarusoke

As you might have read, Cape Town in South Africa is facing its worst water crisis in living memory. As a result, city management has been asking residents to adjust their water consumption to push further the day when it will not make sense to pump water to all corners of the city.

This will happen when stored water in the city's 14 dams is about 13.5% of total capacity - and that will be ‘Day Zero'. Storage is at 24% as of February 2. If residents abide by the city's instructions of using not more than 50 litres per person, ‘Day Zero' will be on April 16. Then, water pumping to suburbs and to non-critical premises will stop. Residents will be required to go to one of the 200 collection points to queue for a daily allocation of 25 litres. In this article, we highlight causes of the crisis and draw parallels with some past events in Uganda. At a later date, we will discuss solutions to the crisis.

The first, and major cause of fresh water shortage in Cape Town is nature, in form of geography of the southern hemisphere. This hemisphere is mainly covered with water - which, heats and cools much slower than the little land available there. This means any fresh water on the land, such as from rainfall or in rivers and dams will evaporate faster because of higher land temperature. The result is that more than 80% of water falling as rain is ‘lost' to the atmosphere - and eventually blown back to the huge oceans encircling the small land.

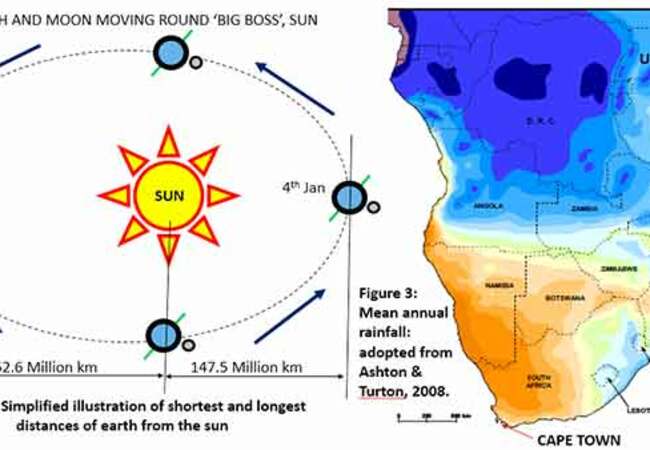

A phenomenon related to Astronomy is the fact that during the southern summer (December-February), planet earth is closest to the sun as shown in the Figure below. The energy intensity received from the sun in the region is then more than that received by similar places in the northern hemisphere during their own summer (June-August) by over 7%. This translates to higher water losses. Moreover, west and south of Lesotho, the land is flat and low lying with no inland lakes or significant river systems.

The scorching sun ensures scant vegetation - leading to the deserts of Namib and Kalahari. On the African continent, apart from the ‘cruel' Sahara desert, Southern Africa is by far the driest and hottest region. There is no place to compare it with in Uganda. Our 'dry' Karamoja is ‘paradise' in comparison. The map shows why.

Although nature has always been like that, climatologists have suggested two causes for the current drought. One is that over time, invasive plant species - like the ‘Tree of Heaven' (Ailanthus altissima) from China and the Aleppo Pine (Pinus halepeasis) from the Mediterranean region have been introduced in the region. They kill native plants, with the latter sucking water out of the subsoil, the way eucalyptus plantations are affecting Uganda's wet lands. A sure path to desertification. Secondly, global warming due to the world's over-reliance on fossil fuels has been suggested. The northern part of South Africa receives summer rains from warm currents of the Indian Ocean. But these have in recent past been affected by high temperatures and corresponding pressures in the eastern Pacific (making the el-nino effects more frequent) - thanks to excessive carbon emissions in the developed northern hemisphere.

The Cape region receives winter rains from cold fronts originating in the southern oceans. Because of the foresaid land denuding, the faster-heating land raises both temperature and pressure inland - so that the cold front effects are prevented from penetrating deep into the interior, where a larger water catchment area would have formed. Consequently, in the recent past, the front has been coming, hitting Cape Town and other coastal cities, moving slightly inwards and going back, having failed to deposit all the water it could have done.

A more interesting man-made cause has been suggested as the increased migration from ‘rural' South Africa to the city since independence. The city population in 1995 was 2.4 million, slightly bigger than present day Kampala. Today, there are 4.3 million residents, an increase of 79%. Dam storage capacity changed from 773 to 898 million cubic metres, an increase of 16%, or only about a fifth of the population rise. The lesson for Uganda and other African countries is clear here: Keep our people spread out in the country by developing rural and regional towns to city standards and interconnect them with first class roads, railways and telecommunication.

Another cause has allegedly been the unease of the ANC central government with the opposition DA (Democratic Alliance) leadership of the Western Cape. The two are counter accusing each other: One says the other failed to manage the water supply-demand properly. The DA says the central government refused to support its large scale sea water desalination plans over the years. This is similar to NRM vs. DP in pre Jennifer Musisi KCC. And as we all know, all stakeholders, including NRM and DP, were the losers in that Ping-Pong game. Politicking and meritorious performance do not mix.

To sum up, we have seen how nature might have been ‘unfair' to the southern tip of our continent in regard to fresh water. We have also seen that man has of late made matters worse. In later articles, we will explore solutions and their effects.

The writer is a Pan Africanist Engineering Don and head of Progressive Africa Solar Engineering Company in Cape Town, South Africa