Gorillas stand in way of Uganda, DR Congo oil

The Government stopped illegal mining of gold, logging and encroachment that were pushing Bwindi to her knees.

ENVIRONMENT

The fact that part of the landscape where the mountain gorillas stay in Uganda and neighbouring DR Congo is sitting on oil, has led to two questions: Should the gorillas be dispersed in order to extract the oil or should the oil and the gorillas just be? The two countries do not agree.

Gerald Tenywa writes about the dilemma of exploration vs conservation.

“We neither have gold nor diamonds, but we have gorillas,” says Amos Agaba, a tour guide at Buhoma in Kanungu district. “They have brought dollars to our village. Tourists buy different products from the local residents and we, too, earn from guiding.”

This is part of the impact of gorilla tourism currently estimated at $10m (sh34b) annually.

Agaba, as well as the local people, who are making a fortune out of gorilla tourism, say three decades ago, Bwindi Impenetrable National Park was a worthless bush. But, Bwindi has turned into a lifeline for the local communities, as well as the endangered mountain gorillas estimated at about 800 in number globally.

The Government stopped illegal mining of gold, logging and encroachment that were pushing Bwindi to her knees. Today, the money from gorilla tourism is making up for the revenue from the destructive use of Bwindi.

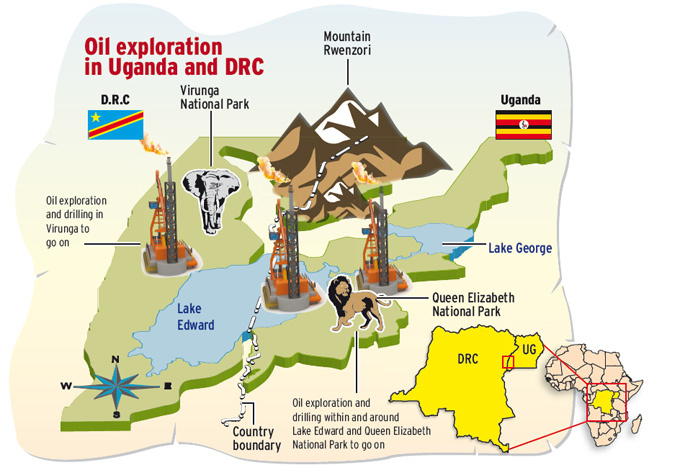

While the Government took a step in favour of conservation, the discovery of oil in parts of Lake Edward and Queen Elizabeth, is beginning to bite the environment. The area, referred to as Ngaji, is part of the Greater Virunga that covers parts of Bwindi, Mgahinga Gorilla National Park in Uganda and Rwanda as well as DR Congo.

The part in Queen Elizabeth National Park is part of the only remaining migratory corridor between Uganda and DR Congo. Lake Edward is at the heart of a chain of lakes, including Lake George and Albert.

The three lakes are connected by Kazinga Channel between Lake George and Edward and River Semliki links Edward to Albert. This is part of the catchment for River Nile that flows through Lake Albert on its way from Lake Victoria to the Mediterranean Sea.

This is, sadly, the area where oil exploration is now being proposed. Exploitation is set to beat conservation. And environmentalists are sad. They argue, among other reasons, that the risk of an oil spill alone is enough danger to the water in the Nile, which will be contaminated to cause destruction of habitats for many migratory species, including fish and birds.

The wildlife based tourism in the Albertine rift, which is one of the most important ecological regions globally will be no more.

It is not only gorillas that are threatened by oil exploration, but other animals, such as elephants

Activists up in arms

As the Government puts final touches to license companies for exploring oil around parts of Queen Elizabeth and Lake Edward, activists, led by Onesmus Mugyenyi, the deputy executive director at the Advocates Coalition for Development and Environment (ACODE) are saying: “No way.”

Mugyenyi, under a coalition of Civil Society Organisation on Oil in Uganda, together with non-governmental organisations in DR Congo, have petitioned the governments sharing the Virunga to leave oil in the ground.

However, government officials argue that this is not the first time that oil exploration is taking place in an ecologically sensitive area. They insist that restoration done in Murchison Falls National Park shows that mining of oil could co-exist with wildlife.

Kabagambe Kaliisa, the out-going permanent secretary in the of the energy ministry, insists that oil activities can be done in a sustainable manner.

“As long as we ensure that oil activities do not pollute the environment,” he says. “The entire Albertine Graben is an area of high environmental concern, with Murchison Falls National Park, Kabwoya wildlife reserves and others. Those organisations should stop politicking and understand that exploration work can go on without damaging the environment.”

Giraffes have been seen grazing in a place that has been restored after the oil exploration in the northern part of Murchison Falls National Park

A decade ago, Uganda discovered commercial quantities of oil. With only 40% of the Albertine rift (the western arm of the rift valley) explored, Uganda’s oil assets are estimated at 6.5 billion barrels and is likely to increase with further licensing for exploration.

DR Congo strategy

However, across the border, DR Congo has opted to leave the oil and preserve the Virunga landscape. The activists, together with the international community, have fought to keep Virunga intact. Consequently, a British company, known as SOCO, has withdrawn interest in undertaking exploration activities in the part of Virunga in DR Congo.

The same pressure could be mounting on the Ugandan government. In the recently concluded round of licencing by the Ugandan Government, private companies declined to take interest in oil exploration activities in the Ngaji block, which is located in the park.

The Virunga is a complex ecological system with chains of tropical rainforests punctuated with lakes, such as Edward; savanna plains and it is also a transboundary park. This means that the impacts in DR Congo are likely to spill over in Uganda and the reverse is true.

“Uganda is a sovereign state, but it will have to ensure that the impacts do not spill over to DR Congo,” Mugyenyi said, advising that Uganda and DR Congo should get a common stand on oil.

UNESCO obligations

In 1925, the Virunga landscape in DR Congo was declared a national park and is currently Africa’s oldest park. In 2008, Virunga became a UNESCO World heritage site.

UNESCO has written to the Government of Uganda stating that the allocation of Ngaji oil block violates Uganda’s obligations under article six of the World Heritage Convention. It states that signatories to the convention must not undertake actions that may damage heritage sites either in their own territory or in the territory of other signatories to the convention.

EU resolution

The European Union (EU) parliament passed a resolution which was adopted last year, in December, calling for measures to protect Virunga, the UNESCO world heritage site.

The statement of the resolution said the area has become one of the most dangerous places in the world when it comes to wildlife conservation.

The parliament encouraged DR Congo to develop sustainable energy and economic alternatives to extractive industries.

“Sustainable management of Virunga’s land, water and wildlife will have direct and indirect economic benefits for communities that rely heavily on the park’s natural resources,” the resolution stated.

According to the 2013 World Wide Fund for Nature report, mountain gorilla tourism alone in the three countries (Uganda, DR Congo and Rwanda) could generate $30m (sh100 trillion) a year and create employment for thousands of people.

“I have seen prosperity at Buhoma because of eco-tourism,” Agaba said. He added: “It has helped to put money in our pockets, yet the environment where the gorillas live has remained intact.”

The Government has spoken through officials like Kabagambe and the decision is to get oil out of the ground. Should Ugandans settle for both-oil and tourism?

Civil societies concerned

Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) want a moratorium on all oil activities in the wider Virunga area and have appealed to the international community to weigh in.

Ugandan government intends to allocate a new oil exploration licence for the Ngaji block.

“We call on UNESCO and the governments of Uganda and the DRC to reach an agreement to prevent any oil exploration, extraction or related activities in the wider Virunga area,” a statement authored by CSOs in Uganda, DRC and international conservation bodies, reads.

The organisations want all existing exploration licences in this area to be cancelled and plans to issue new ones.

The Virunga region includes Virunga and Queen Elizabeth national parks and the whole of Lake Edward.

They say DRC should refrain from granting any new licences, or transfer of licences in Virunga National Park or seeking to re-draw its boundaries to allow oil activities in the area.

Last year, SOCO International carried out seismic testing on Lake Edward in Virunga National Park, but the company has not yet published the results of its exploration.

Following widespread local opposition and a international outcry, SOCO International committed to no further involvement in its oil block in Virunga and has since announced that it no longer owns the licence.

They also state that Virunga National Park, as a UNESCO world heritage site, has an outstanding universal value that includes a wide diversity of habitats as well as exceptional biodiversity, notably endemic species and rare; globally threatened species, such as the mountain gorilla.

An estimated 200,000 fishermen and local people depend on the lake for their livelihoods and a valuable source of protein.

“Before companies explore oil, they have to factor in restoration”

As much as oil could turn around the economic fortunes of countries, it poses a serious risk to the environment. The excavations could scare away wildlife and block migratory corridors.

So, is it possible for oil and conservation to co-exist? In the protected areas, such as Murchison Falls National Park and outside protected areas like Buliisa, Yusuf Zziwa, a health and safety officer under Total, has been ensuring that oil extraction does not destroy the environment.

Together with other experts, they have been working out a way how oil and tourism can work harmoniously and according to international standards.

“Before companies undertake exploration work, they have to factor in restoration — assisting the recovery of the site that has been disturbed,” Zziwa said.

Oil drilling requires removal of soil. This soil is kept aside and returned to the site after extraction.

The ultimate goal is to return the landscape to its original form. Zziwa says the placement of the soil follows contours.

“We ensure that the soil is not eroded or contaminated with the introduction of invasive species. Then we support the sites to regain the vegetative cover. We select indigenous species of trees, grasses and monitor the site,” he added.

“It also involves monitoring the site for some time.”

As proof, Zziwa and Linda Nabirye, the spokesperson at Total, showed Saturday Vision a place that has been restored after the oil extraction in the northern part of Murchison Falls National Park.

Elephants and giraffes were grazing on the area that had been maintained to reinstate the connectivity and environmental stability.

“The animals have returned and are grazing in the restored areas,” Zziwa says.

So far, Total has restored 63 sites and has handed 22 oil wells to the Government and the land owners, according to Zziwa. He says Total is working on another 41 areas, which have been restored, but are being monitored.

However, there are some sites where experts from Total and National Environmental Management Authority, Uganda Wildlife Authority and the district officials, noticed soil erosion and pools of water.

“We have been monitoring them for one-and-half-years,” he said, adding that the situation has also improved. Reaction from NEMA Naome Karekaho, the head of corporate affairs at NEMA, commended the oil restoration activities.

“The oil and gas sector is where we have demonstrated sustainable development that has helped us to have both oil and conservation,” Karekaho said.

“It takes discipline and commitment on the part of the companies and the regulators.”

She believes that with better technology at Ngaji block, Ugandans could have oil without hurting conservation.

UWA speaks out Edgar Buhanga, the deputy director of UWA said apart from gorillas, Virunga has one of the only wild landscapes where migration of large mammals between Uganda and DR Congo has been left uninterrupted for centuries.

Buhanga says they were taken to the US, where mining is taking place and impacts have been reduced. He believes the same thing could be replicated at Ngaji.