Inclusive education: The missing link

Slow action, limited funding; the long bumpy journey for children with disabilities may get better.

INCLUSIVE EDUCATION: PART IV

Slow action, limited funding; the long bumpy journey for children with disabilities may get better

The Government continues to preach inclusive education for all children of school-going age regardless of their ability or disability. Why then are many children with disabilities out of school? In this fourth and last part of our series, Stephen Ssenkaaba presents the contradictions that have kept many children with disabilities outside of an inclusive system of education. He also shares examples of countries where inclusion has worked and practical solutions to the problems that beset Uganda.

For a long time in Uganda, people with disabilities were regarded as sick or disadvantaged. There was very little effort to recognise and enable them enjoys their rights. Often, parents never sent children with disabilities to school.

The first school for children with disabilities was established at the request of the colonial, Governor Sir. Andrew Cohen. St. Francis School for the Blind Madera in Soroti district was founded in 1955 by the Little Sisters of St. Francis congregation.

Later, special schools like Kampala School for the Physically Handicapped (1969), Ngora School for the Deaf, Buckley High Primary School in Iganga, Kireka Home for Special Needs and a few others, were set up.

According to research by Jacqui Mattingly and Martin Babu Mwesigwa, the Government support for special needs and disability education evolved slowly, with religious and non-governmental organisations taking the mantle of supporting and financing most disability and special—needs initiatives. It was in 1983 that the education ministry, established a department of special education. Four years later, the Kajubi commission recommended more Government support for special needs education.

Mattingly and Mwesigwa also note that, "Initially, the Ugandan Government had no policy on training teachers in special needs until 1992, when it established a policy on ‘Education for National Integration and Development'. "Here, the Government pledged to support special needs education by providing funding and teacher training.

A 1991 Act of Parliament mandated the Uganda National Institute of Special Education, UNISE, (now Faculty of Special Needs and Rehabilitation, Kyambogo University) to train special needs education teachers," they write.

The first major government programme on disability and special needs was established in 1992, when the Government,in collaboration with the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA), implemented the Educational Assessment and Resource Services (EARS) programme.

The programme led to the education ministry establishing a department of special needs education/guidance and counselling and a policy framework for educationally disadvantaged children. It also provided resources for offi ce accommodation at the districts, small homes at schools, resource rooms, school facility grants and procurement in 45 districts. The programme wound up in 2003.

SHIFT TOWARDS INCLUSIVE EDUCATION

More proactive approaches to special needs and education of children with disabilities were adopted as Uganda ratified various international conventions on child rights which, among other things, emphasized inclusion of children with disabilities in education and other services.

As a signatory to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (2008), the country committed to observe and protect the rights of all individuals.

The 1995 Constitution through articles, 21, 32 and 34, also provided for recognition of people with disabilities and the right to education. The Disability Act of 2006 made an even stronger case for inclusion of children with disabilities in the education system.

The Government also ratified key education instruments such as the World Declaration on Education For All (EFA) framework to meet basic learning needs for children (Jomtien, 1990), the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education (1994), the Dakar Framework for Action (2000), and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). All these underscored equal and fair access to education for all children.

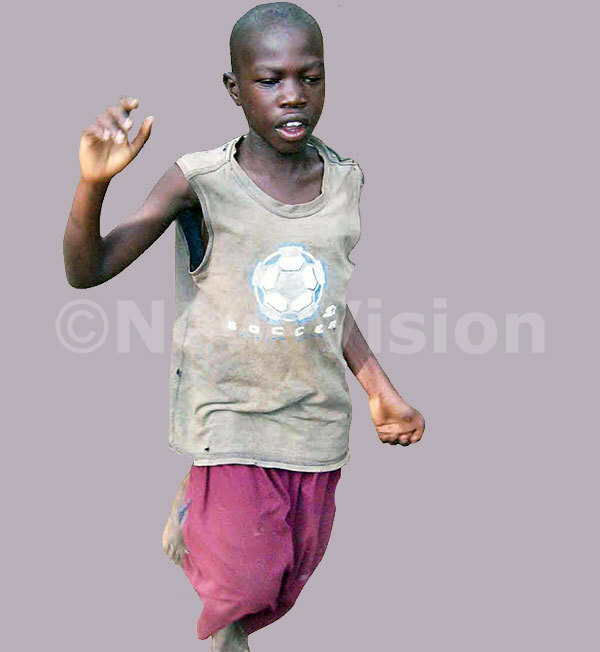

A physically challenged pupil learning to walk. (Credit: Geoffrey Mutegeki Araali)

INCLUSIVE EDUCATION STILL WANTING

Since the inception of the Universal Primary Education programme in 1997, Uganda has encouraged inclusion for all children in primary schools, regardless of their special needs and disabilities.

But, nearly 15 years later, children with disabilities remain marginalized and not properly integrated into inclusive education.

"Even though millions of children have been able to access primary education, the needs of children with disabilities have not been adequately met under UPE. This makes children with disabilities lag behind as far as access to education is concerned," says Dolorence Naswa Were, the executive director of Uganda Society for Disabled Children.

Inadequate facilities, absence of trained teachers and prevailing negative attitudes on disability in schools are some of the major hindrances to education for these children.

LIMITED FUNDING

Where inadequate scholastic materials and school facilities are concerned, fingers are pointing to the dwindling government funding for special needs education programmes. For instance, out of the sh1.76 trillion education sector budget for the 2013/2014 financial year, sh2.16b (0.12%) was allocated to special needs education programmes; only a little more than the Sh1.68b allocated in 2012/13 and sh1.89b for 2011/2012.

The next financial year's projections indicate that this funding will reduce even more to sh2.06b.

"With such limited funding, planning and allocating requisite resources to schools has been difficult," says Edson Ngirabakunzi, the executive director of the National Union of Disabled Persons of Uganda (NUDIPU).

Teacher training also suffered a setback when the Government reduced the number of students it sponsors to study special needs courses at Kyambogo University from 30 some years back to only seven as of today.

"Considering the high cost of training in this field, many interested teachers cannot afford to enroll as private students. As such, fewer and fewer teachers are being trained to go out and teach in schools," Asher Bayo, the acting dean of the faculty of special needs and rehabilitation at Kyambogo University explains.

Out of the faculty's sh1.6b budget, the Government has offered only sh700m this financial year to meet the huge costs for training and research.

With three quarters of this budget spent on lecturers' wage bill, very little remains to meet the costs of other key training components for a faculty that has only 10 functional braille machines, two television sets and one video camera.

Since the closure of the EARS programme 10 years ago, the structures and facilities put in place under the programme are no longer functional.

The vehicles and buildings were turned to other purposes. The wanting support for special needs and disability education programmes has been attributed to slow government action.

"We have been engaging with key education stakeholders, including the Ministry of Education, district education officers and teachers to address these problems. We still wait for action," NUDIPU's Ngirabakunzi says.

A pupil of St. Francis Primary School for the Blind in Soroti district

standing near a window with a broken glass. Some of the infrastructure in schools for children with special needs is wanting. (Credit: Geoffrey Mutegeki Araali)

WHAT HAS THE GOVERNMENT DONE?

The Government through the Ministry of Education and Sports, says it is doing all that is possible, despite not having enough funds to provide all that is needed.

"We definitely understand that this is not enough. Our aim is to provide additional support that can keep children with disabilities and other special needs going," Francis Akope, the principal education officer for inclusive education at the He explains that even though facilities are not enough, there is something on the ground to keep the system going and where it is not sufficient, the ministry cannot do much to change things because the funds are not enough.

"We hope that most children with special needs can be catered for under the inclusive system, but where this is not possible, we still maintain special needs schools and units in Mindful of the needs of children with special needs in schools, the Government provides a small subvention of sh2m to sh3m every term to each government-aided school that is known to have children with special needs.

This money caters for light meals, first aid and scholastic materials for learners. The Government has also drafted a policy on special needs and inclusive education which, on implementation will ensure that more funding and better facilities are provided to boost special needs education. Unfortunately, the Cabinet approval of this policy has been delayed due to lack of funds.

Schools have also complained that the sh3m subvention is just a pittance and, like the UPE capitation grant, sometimes does not come on time.

LESSONS FROM OTHER COUNTRIES

RWANDA

According to the DFID 2011 report on inclusive education assessment in Uganda, through its child-friendly schools initiative, Rwanda has established an improved school environment with better teaching methods and psychological support for all learners, particularly girls and other vulnerable children such as those with disabilities.

Under this arrangement, high standards are set for teaching methods and curricula, sanitation facilities, and the provision of sports and co-curricular activities.

The programme also utilises peer-group clubs, mentoring, and community activism.

Schools under this initiative were the first in the nation to mainstream children with disabilities, with 7500 being served as at 2009. Today, the child-friendly programme is in all schools and has also been adopted as the basic standard for all primary schools in Rwanda.

ZAMBIA

The Ministry of Education policy in Zambia recommends that children with special education needs remain in the regular school system. This followed a 1999 child-to-child twinning pilot project called the Mpika Inclusive Education Project. Under this project, children with disabilities were put together with their ordinary counterparts to explore issues around disability and exclusion. The exercise was co-ordinated by teachers who afterwards delivered school based training sessions for other teachers in their own schools to raise awareness of inclusion.

Today, thanks to the policy, children with disabilities are more accepted in regular classrooms and some have gone on to high schools. There has also been a change in attitudes in the community towards children with disabilities.

KENYA

In Oriang province, a holistic participatory approach encompassing teacher training, community involvement, child-to-child initiatives and improving the environment, has been in place since 2002. Training focuses on the enhancement of skills that empower the teachers to stop viewing children as a group of learners, but as individuals with diverse learning needs. Through training, the teachers have been encouraged to adopt a much more eclectic reflective approach in their teaching. This is to ensure that the teachers are not only sensitive to the children in their classrooms, but are also able to share with colleagues and support parents. Parents are encouraged to host meetings, workshops, share experiences and support each other to supplement teacher input, training and raise disability awareness among the community members. Community-based rehabilitation is provided using community health workers to administer and train parents in basic physical therapy activities and primary healthcare initiatives such as epilepsy management.

A visually impaired child

IMPLICATIONS AND WAY FORWARD

Unless proactive measures are adopted to change the situation, many children with disabilities will miss out on life-changing education opportunities. This implies not only violating their rights to education, but also failing to attain the education for all and MDG2 targets. It will also further entrench poverty among people with disabilities.

According to the State of the World's Children 2013 report, once children with disabilities miss education, "it means that many more children will be denied the lifelong benefits of education: a better job, social and economic security, and opportunities for full participation in society."

WAY FORWARD

"We need to plan for inclusive education so that it becomes entrenched. It is about mapping out the steps towards achieving inclusion within a specified time. Specific attention needs to be paid to some of the issues that impede access to education for learners with disabilities such as curriculum and teacher c o m p e t e n c i e s , " Dolorence Were, the executive director of Uganda Society for disabled children.

FIGHT DISCRIMINATION

According to the State of the World's Children 2013 report, discrimination lies at the root of many challenges confronted by children with disabilities. Apart from being implemented in law and policy, the principles of equal rights and non-discrimination should be reinforced by enhancing awareness of disability among the general public, starting with those who provide essential services such as education.

International agencies and their governments should provide officials and public servants with a deeper understanding of the rights, capacities and challenges of children with disabilities so that service providers and policymakers are able to prevail against prejudice.

IMPROVE FUNDING

Ngirabankunzi says funding to special needs education should be increased from 0.12% to 1% of the education sector budget. "We also call for recruitment of special needs education officers to ensure proper inspection in schools," he explains.

TEACHER EDUCATION CURRICULUM

"We need to make reforms in the teacher education curriculum to enhance aspects of special needs and disability studies," says Dr. Stackus Okwaput, the acting head, community and disability studies department at Kyambogo University.

He explains that, for instance, instead of teaching the course on special needs education as a subsection under the professional education studies programme, this course should be taught and examined separately. That way, much more importance and support will be accorded to it.

STREAMLINE ASSESSMENT

A system should be developed for the identification, assessment and placement of children requiring special needs education.

"This should be seen in terms of the support the children require in order for them to participate in school and not in medical or other negative terms relating to their condition," states the Department for International Development report.

CONCLUSION

Despite all the commendable efforts to make education accessible to all children, those with disabilities continue to face challenges. Poor planning and lack of funds are at the heart of this ongoing situation. It will take more than just government action or non-governmental organization involvement to solve this problem, which has now made our hopes for education for all even more distant.

[The series were done with support from the African Centre for Media Excellence (ACME)]

(This article was first published on Thursday, November 13, 2014)