Nsibirwa hall, Makerere's retired war 'general'

Apr 29, 2015

Around the late 1948, three years after World War II, Uganda didn’t have much of an architectural marvel to talk of really.

At a glance, Nsibirwa hall, by most accounts Makerere University's retired war general of sorts, looks every inch like a former frontline combatant. Laid-back and almost subdued, the hall, once a wonder hall with all the tidings of an army barracks, now only quietly exists.

With its horns clipped and residents now very ‘sober' beings who follow the rules to the letter, what you now see are the scars from its former frontline exploits. A limbless sculpture here, a broken window there. An old flag post here missing its flag because it was outlawed, a new signpost there with the hall's name reading N.S.I.B.I.R.W.A, instead of Northcote.

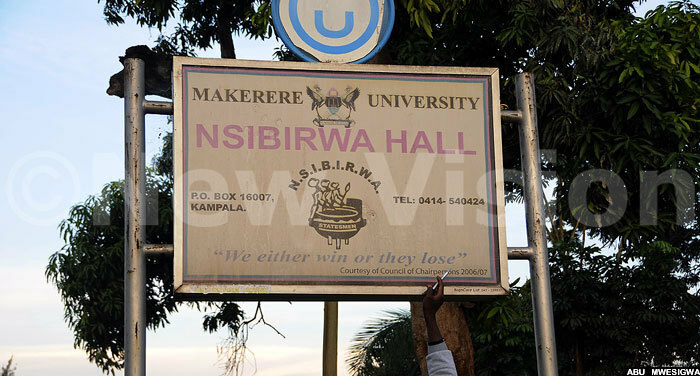

WINNERS FOREVER: "We either win or they lose", reads the motto

Clearly, you see that the hall has been to the school of hard knocks, its ‘warrior' autograph slowly fading away, bit by bit. And that is because Northcote, a name that among some circles is believed to have infused in the hall's residents a combatant streak, is no more. How true that conspiracy theory is remains a mystery.

But Northcote, for those who followed the Makerere University story of yester-year, was a wonder hall - the story of that bad guy in a movie, who, for some reason, you don't want dead. That is why in the Northcote era, the air around the university hung thick with the name. Visitors always wanted to go to, and actually touch the walls of, this hall that made the pages of the country's newspapers, with mostly intriguing stories, stories sometimes of sheer hooliganism.

Still the stories made it to the pages, and though you couldn't write home about them, you couldn't resist reading them. In fact, one of the former residents of the hall even erected a commercial building on Mityana Road and named it Northcote.

The Northcote legacy

Around the late 1948, three years after World War II, Uganda didn't have much of an architectural marvel to talk of really. We are talking marvel in the sense of size - forget about engineering sophistication and the like, we still don't have much of that.

Anyway, at the time, the British government was feeling generous, having been one of the big five victors of World War II, the other four being America, USSR, France and China.

"So, in late 1948, the British government embarked on an ambitious building project on Makerere hill, which would be a donation towards Uganda's education. When complete in 1951, that building would become Northcote hall, with two blocks currently Nkrumah and Nsibirwa halls," recalls Bernard Kaija, Nsibirwa hall's custodian.

He has served in that capacity on and off for a period amounting to 14 years, and has served Makerere University for 43 years now.

According to available literature, Northcote - with its over 400 rooms - also became the biggest building in the country at the time, an architectural marvel of sorts since Ugandans were not used to such big structures.

"Even though Makerere had been around since 1922, its other halls of residence, like today's Mitchell, were smaller and subdivided into blocks. So, Northcote was the only hall of its kind then, first occupied in 1952," Kaija recalls.

Named after Sir Geoffrey Northcote, who served as chairman of the University Council from July 1945 to 1948 when he died, the hall is said to have picked up its character after the person it owes its name to, who is said to have been a no-nonsense, principled leader.

And with such milieu as the hall being the first of its kind, complete with sleek architecture set both in the medieval and modern times, its residents got high on it, and actually started believing they were special. It didn't help matters that the building actually resembled the Royal College of Music in West London, still in place today.

So, high on all the cool perks, the Northcote residents went to work, picking up all the attributes of cockiness in the book, and touting Northcote as a state of its own, independent of Makerere, thus, Northcote State.

And its residents? Well, they called themselves statesmen or officers, governed by four main pillars: Supremacy, Superiority, Speed and Determination, abbreviated as SSSD.

Each of them was tasked with a role of promoting brotherhood, a solidarity tool that came in handy when student mobilization for war or any other communal undertaking was needed.

At such times, they invoked their coded term, "Weewe", which called upon them to "act together, do what we want and we go."

They were also to live by a code of secrecy, which prevented one from telling on a brother, just like it is with the Italian mafia code, Omerta. Years later, this secrecy code, which all the statesmen exercised by the book, would come in handy, or rather prove detrimental, depending on who got the bloody nose, or who gave it!

Then they came up with a motto: "We either win, or they lose."

This motto gave them a sort of combatant vein, little wonder they christened their leaders generals, with Gen. Kale Kayihura, the Inspector General of Police, and singer General Mega Dee, now one of their renowned exports several years down the road.

The generals had to have a governing body, so they came up with a council known as Northcote State Supreme Revolutionary Command Council (NSSRCC), chaired by a General - Kayihura (pictured below, present day) chaired one of these at some point, according to Kaija.

Interestingly, this council conducted its meetings in an attic up in the hall's ceiling, and the council's members practiced sleeping with one eye open, albeit without much success. And when asked why they did so, their answer was always, "just in case, you know."

"Meanwhile, all this went on under the watchful eye of Dinwiddy, the hall's first ever warden, and he actually helped a great deal in aiding them deck themselves with all sorts of titles," says Kaija.

All this was a part of an established leadership code, which united them under one character - spirit. That defined their strength, which is why they also referred to themselves as spirits. That spirit, a very important code, was to be the silver lining in all the things they indulged in thereafter, and they did it all together - in spirit.

To strengthen this code, Dinwiddy bought them a drum, a huge legged drum they called the Spirit Drum aka Stereo. This drum, guarded by an army of officers, became the hall's spirit symbol, and it was sounded in spirit (by many people) at every Northcote function, including initiation of ‘freshers' and celebration of success in one of the hall's exploits, some legit, others sheer madness celebrations.

They also commissioned a number of sculptures, each with a specific symbolism.

A STROLL INTO HISTORY: Nsibirwa hall is a ghost of its former majestic self

The lion's sculpture, which spoke of each of the residents as possessing a lion's heart, had a lioness as a companion sculpture, to complete the spirit of togetherness.

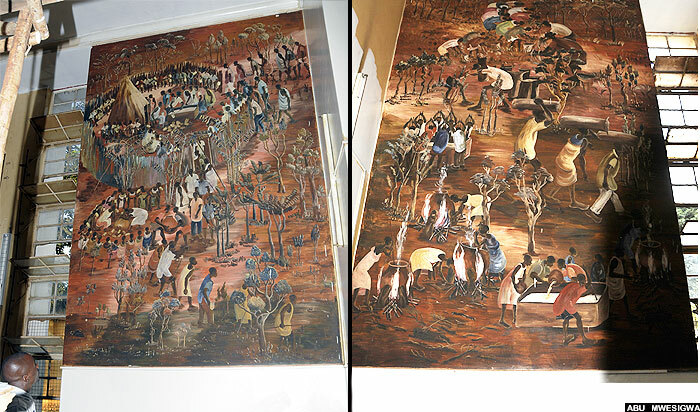

The sculpture of goats teaming up to tackle a common enemy also had a spirit attribute to it. The very old mural paintings (pictured below) in the dining hall, done by former Makerere lecturer and artist Sam J. Ntiro and still there to-date, show people trying to accomplish a task in a group, which goes back to the spirit.

Also in a spirit-laden breath is the sculpture of students marching in solidarity, guarding another sculpture - the "all-seeing, invisible and all-powerful" Lollipop, a rather highly respected and rare streak of lion, with both human and lion attributes.

Lollipop, who happens to still be present outside Nsibirwa hall (in a newer version though), is another of the hall's very important cultural symbols still around from the Northcote days.

Once in a while, residents gathered (and still gather) to give allegiance to Lollipop.

"We do it once in a while, though the most notable is when we have won something, say in sports or after a battle. We gather together and give thanks to the all-seeing, invisible and all powerful Lollipop," says Lawrence Nsimbe, a former disciplinary minister.

The statesmen also had other important stuff; a tractor for ferrying the spirit drum, that was referred to as the "state car" (you were never allowed to refer to it as a tractor). Important too was the warden, referred to as a "burden"; other staff workers referred to as "Northcoters", and Arua Park, a quadrangle they took pride in, for it's where they gathered to set off for any confrontation.

Also in Arua Park, they came together during good times and sipped at highly potent local brews, while paying homage to the "all-seeing, the invisible and all powerful Lollipop" - you always had to invoke all his attributes, not just blurt out "Lollipop".

Paying homage to Lollipop was never complete without singing the hall anthem: Oh Lord you know, I am a bachelor boy, till summer holiday. My Lollipop!

This anthem pledges respect to Lollipop, and promises him that they will remain bachelor boys, except when it's summer holiday. Summer holiday is actually for when they find a girl, not the real summer holiday.

Northcote parts ways with New Hall (Nkrumah)

Spot the two longest buildings down south? Yes, they are Nsibirwa and Nkrumah halls. (Credit: New Vision archives)

With time, it became hard to manage so many ‘crazy' chaps spread across two huge blocks. And since the upper block had been pushing to secede from the lower one and manage their own affairs, the University Council, around the 1960s, split the hall into two. The lower one stayed Northcote, the upper, New Hall - a name that stayed until 1975, when the hall picked its present-time name, Nkrumah, after Ghanaian revolutionary Kwame Nkrumah.

Northcote refused to acknowledge New Hall as an autonomous state, so they christened the hall Kabinda, after an enclave that was fighting to break away from Angola, in an old land dispute.

With Northcote passing ‘Kabindists' off as a people from a hall with an identity crisis, enmity started brewing between the two siblings. Between 1976 and 1977, shortly after New Hall changed to Nkrumah, a move was hatched at Nkrumah to cripple Northcote on the one moment they let their guard down.

One night, as a ball went on at Northcote, a team of Kabindists sneaked away the Spirit Drum and sold it to Lumumba, a hall that had opened in July 1971, 19 years after Northcote had already established an elaborate cultural ideology, complete with symbols, a thing that always overshadowed.

Pictured is part of Nsibirwa hall today

So, a chance for Lumumba to kill Northcote's clout was always welcome, any day. And on this night, ‘Lumumbists' didn't waste time - they simply hacked the Spirit Drum to ‘death'. By morning, the very dear drum, an important Northcote unifying factor, lay in pieces at Lumumba.

It is said that on that morning, the Statesmen cried, shedding real tears; and declared that a year of mourning. The generals organized a squad that matched to Lumumba in the night. The mission? "To kill or be killed, and also demolish Lumumba to the ground," says Kaija.

"Some of the Statesmen, real soldiers who had returned from the frontlines of the many political wars Uganda was embroiled in about the time, had guns and were ready to use them to kill Lumumbists on sight. Police had to intervene, and I must say they saved a bloodbath about to happen right before our own eyes. That was scary," recalls Kaija, who by then had been Northcote's custodian since 1975.

A LONG WAY DOWN THE ROAD: History that has been left in tatters

The University Council had every Lumumbist pay a fine every semester for almost two years.

Since then, there has always been bad blood between Lumumba and Nsibirwa, the only thing saving them from each other being the distance. "We kept buying several drums afterwards, but they all never lasted," says Kaija.

Also, Northcote and Nkrumah never looked eye to eye, seeing as they were the ones who stole the drum in the first place. Making matters worse was that they also liked the same girl.

The war over a girl

About the time Northcote and Nkrumah were no longer the same hall, Africa, a girls' hall, opened next door in what presented a girl up for grabs.

See, Lumumba hall has a girl, Mary Stuart aka Box, hence the solidarity Lumbox. Mitchell's girl is Complex hall, hence the Mitchellex solidarity. Other halls too have girls. So, Northcote too wanted in on the cool digs. Ditto his sibling, Nkrumah. They bickered, each hall taking turns using a footpath shortcut to Africa to impress the girls that they were the dudes for them, in what is called benching.

Often, the siblings encountered each other in the shortcut and a real showdown ensued. Closely watching the drama was the nearby Livingstone hall, whose boys were calmer, more respectful and had no drama. Touting themselves as gentlemen, the Livingstoners saw an opportunity to marry the Africaners.

While Northcote and Nkrumah bickered over the girl, Livingstone flattered her, christening her a lady, promising her a better future and smearing egg on the faces of the warring siblings. It didn't help that the shortcut, famously known as the panya, got blocked thereabout.

In the mix, the joke was on Northcote and Nkrumah, as Livingstone and Africa said "I do" to each other in what led to the Afrostone solidarity. Northcote left a sore loser, and always had it in for Afrostone.

The fall of Northcote

Nsibirwa hall was once high up there. Today, it's a retired war 'general', you could say

A chance presented itself for Northcote to seek vengeance.

On May 4, 1996, as an anniversary party to celebrate the union between Livingstone and Africa simmered, a group of about 25 statesmen marched to the kitchen where the party food was being prepared and subdued the cooks. Acting under their maxim: "Maximum malice will cause maximum sabotage with impunity", they poured in the sauce a concoction of an estimated 7kg of pepper and salt (not mashed glass as held by legend), bringing the party to its knees.

Back in their hall, the code of secrecy ensured everyone stayed tight-lipped amidst investigations by the dean to nail the 25 perps. With the investigation going cold and not a single name turning up, the University Council suspended every resident and closed the hall.

About a month later, the generals regrouped and sent word around in what led to a revolution where the suspended residents reoccupied the hall forcefully. A protracted battle between the police and the statesmen ensued, with the statesmen eventually giving up due to lack of enough fire power.

At home, students started cracking up, so they volunteered names in confidence. In August 1996, about 30 Northcote residents, including then-Guild President Stephen Renny Galogitho, were expelled.

All the other 270 continuing students were asked to commute, on top of losing their student allowances.

The void at Northcote was filled up by students registered to other halls, but who hadn't been resident. Also, the name Northcote took the backseat for Hall X. After a year, on August 12, 1997, it changed from Hall X to Nsibirwa Hall, after Martin Luther Nsibirwa, a former Katikkiro of Buganda, who between 1919 and 1920, lobbied the Kabaka to give Makerere hill land to Makerere College, which enabled the expansion to Makerere University in 1922.

"Today, there's no Northcote, and most of the symbols and cultural significance have since died with the name. Because the students were denied to unfurl their flag, now a memento in the warden's office; and their main symbol changed from the spirit drum to a pot, the fascination with the hall culture has died. There isn't much of brotherhood today, and the culture of communal work has died," says Kaija, with a somewhat sense of nostalgia shrouding his demeanor.

Today, what used to be the jealously guarded sculptures are now deformed remains (like the one pictured below) and stumps, while others are long gone, perhaps stolen.

Poor Nsibirwa sits there with that deafening quietude of a war hero who has been there, done that, and who with age has grown wiser and quieter, probably reflecting on the old days and going like: "Who the hell gave me these very sober residents?"

Well, at least the sober residents still secretly pass off the name N.S.I.B.I.R.W.A as an abbreviation for Northcote State Is Brilliant In Revolutionary War Affairs. That is why there are dots between the letters of the hall name, on the signpost. That counts for something, doesn't it?

Some prominent former residents

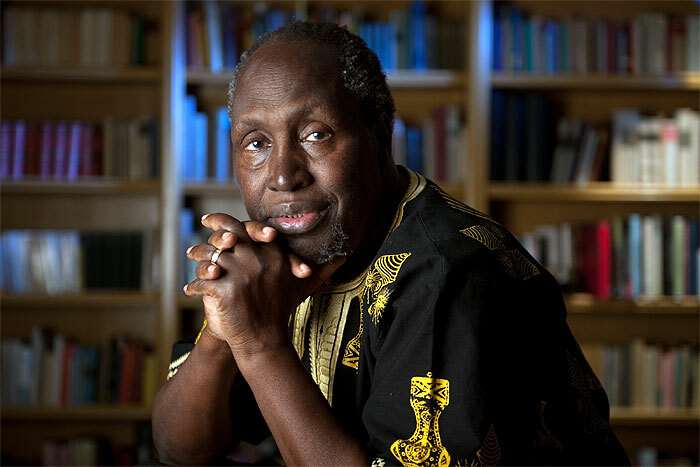

Prof. Ngugi Wa Thiong'o (pictured) - renowned African author, remembers his time in Northcote.

I lived there 1959-1964. In some ways Northcote was a literary experience for me. It was where I was born as a writer. I wrote my plays, The Rebels (One Act); The Wound in My Heart (One Act), in and for Northcote in the inter-hall competition. My first major play, The Black Hermit (Three Acts), written for Uganda Independence, I wrote in Northcote Hall. Also my first novel, The River Between.

Altogether, as a Northcoter, I wrote two novels; eight short stories; three plays, and over 60 articles for the Sunday Nation under the title: As I see It. I also wrote for Transition, The New African and of course Penpoint. All of them from my room in Northcote Hall.

The warden, Dinwiddy, was a most inspiring presence; his laughter was infectious; he was among the earliest to take an interest in my writing, even reading and commenting on the early draft of The River Between.

I believe that Northcote Hall was the site of the now historic conference of African writers that brought together luminaries like Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Langston Hughes (USA) and locals, like myself and John Nagenda.

I remember Northcote Hall also for the murals in the dining room. I hope the Makerere establishment preserves those murals. Some were painted by Sam Ntiro. They are of immense historical value.

Northcote Hall dining room was also the site of memorable social evenings with ladies from Mulago and Mengo, etc, etc.

Other known former residents

Hon. Abdu Katuntu (pictured above) - Member of Parliament, Bugweri County

Prof. Adonia Tiberondwa - Teacher and politician

George Kihuguru - Former Dean of Students Makerere University

Basil Bataringaya - Former Minister of Internal Affairs

Gen. Kale Kayihura - Inspector General of Police of Uganda

Emmanuel Dombo - Former Guild President, MP Bunyole East

In case you have a social story in regard to the old good times about school or institution, and would want to share it for publication, please write to the editor at mwalimu@newvision.co.ug