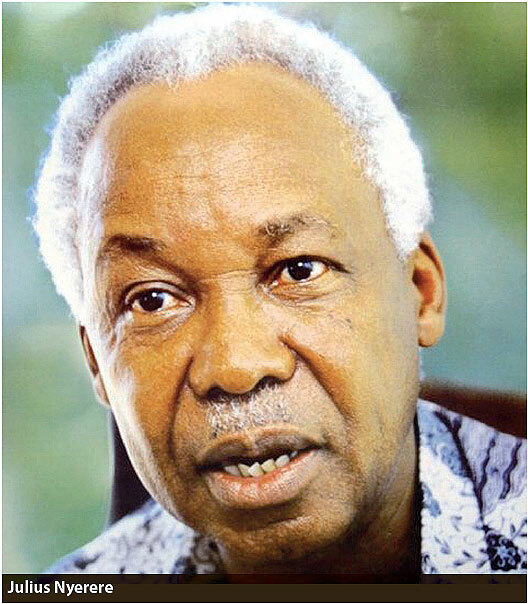

Julius Nyerere, the godfather of Uganda's political set-up

Today, JOSHUA KATO brings you the life and time of Julius Kambarage Nyerere, the first president of Tanzania, controller of all affairs in Uganda and a politician by calling

To mark 50 years of Uganda’s independence, New Vision will, until October 9, 2012, be publishing highlights of events and profiling personalities who have shaped the history of this country. Today, JOSHUA KATO brings you the life and time of Julius Kambarage Nyerere, the first president of Tanzania, controller of all affairs in Uganda and a politician by calling

At the height of Idi Amin’s bloody rule in the late 1970s, Nyerere was one of the few leaders the world over, who sacrifi ced their country’s resources, both fi nancial and human, to rid Uganda of the brutal regime. Any wonder then that in 2007, President Yoweri Museveni awarded him the Katonga Medal, Uganda’s highest military award, in honour of his contribution to the struggle against colonialism and Idi Amin?

Julius Nyerere was a personal friend of Milton Obote, which is one of the reasons his infl uence in Uganda became easier.

In June 2011, prayers were held at Namugongo Martyr’s Shrine for Nyerere, in which President Museveni made one of the brightest eulogies about him: “I am happy when I speak of Nyerere because I am his supporter. He was the greatest black man that ever lived. There are other black men such as Nelson Mandela and Kwame Nkrumah, but Nyerere was the greatest...,” Museveni said. Between 1979 and 1980, Tanzanian leader Julius Nyerere was the ‘defacto’ president of Uganda. Nothing was done without consulting him and anything attempted without consulting him was quashed.

“Even if you wanted to sneeze or move your leg, you had to first inform Julius Nyerere about it,” mused late President Godfrey Binaisa, in his testimonials, Binaisa ne Yuganda. That was the depth of Nyerere’s infl uence in Uganda. It is easy to understand why Nyerere is attracting all these praises. At the peak of the anti-Amin struggle, many Ugandan exiles — politicians, academicians and otherwise, sought refuge in Tanzania, and were directly aided by Nyerere.

Among them were Milton Obote, Yoweri Museveni, Oyite Ojok, Tito Okello and Bazilio Olara Okello. When time came to organising and hosting the Moshi Conference in 1979 to determine Uganda’s future, Nyerere was at the forefront. Most anti-Amin fi ghters were in Dar-es-Salaam with their families, all funded by Nyerere

“The good people in Mwalimu’s office assisted us to get an apartment in another neighbourhood called Upanga,” Janet Museveni, who too was in Tanzania with her husband, Museveni, recalls. “Milton Obote was living in the presidential guest house in Musasani, supported by Mwalimu’s government,” Janet wrote in her book My Life’s Story. It was also clear that on Obote’s behalf, Nyerere was willing to fight

Amin.

“On return to Dar-es-Salaam, Nyerere told me the Tanzanian army had suggested that if I could fi nd a pilot, some of my men could be fl own to Entebbe on the night of the invasion. The plan was for the government of Tanzania to commandeer an East African Airways aircraft from a Tanzanian airport,” Obote wrote.

He adds: “From 1973 to 1978, I requested president Nyerere to allow me to arrange for the infi ltration of the men to Uganda, but the president who was always very kind to me; he used to come to my residence, sometimes twice a week, for conversation and would invite me to functions at his house.”

Obote also wrote that when Idi Amin’s forces invaded Tanzania via Mutukula on the Ugandan southern border president Nyerere briefed him and concluded: “This is the opportunity we have been waiting for.” This culminated into the struggle led by the Tanzanian army and the Ugandan exiles that ended the bloody rule of Idi Amin in 1979.

Apparently, Nyerere had learnt that sections of Ugandans did not want Obote to return as president. This is why he accommodated other fi ghters like Yusuf Lule, who later became President after the toppling of Amin, and Godfrey Binaisa. Earlier, while Obote had advised Nyerere against bringing a young man called Yoweri Museveni closer, Nyerere embraced Museveni. You can as well argue that other than Idi Amin and Sir Edward Mutesa, all the other Ugandan presidents, seven out of the nine, had Nyerere’s blessing.

Political career

Upon his return to Tanganyika, Nyerere taught history, English and Kiswahili at St. Francis’ College, near Dar-es-Salaam.

In 1953 he was elected president of the TAA, a civic organisation dominated by civil servants. In 1954 he transformed TAA into the politically oriented Tanganyika African National Union (TANU). TANU’s main objective was to achieve national sovereignty for Tanganyika. A campaign to register new members was launched, and within a year TANU had become the leading political organisation in the country.

Nyerere’s activities attracted the attention of the colonial authorities and he was forced to choose between his political activities and his teaching career, to which he reportedly said: “I am a schoolmaster by choice and a politician by accident.”

He resigned his teaching position and traversed the country, speaking to common people and tribal chiefs in a bid to garner support for the movement towards independence. He also spoke on behalf of TANU to the Trusteeship Council and Fourth Committee of the United Nations in New York.

His oratory skills and integrity helped Nyerere achieve TANU’s goal for an independent country without war or bloodshed. The co-operative British governor Sir. Richard Turnbull was also a factor in the struggle for independence. Nyerere entered the Colonial Legislative Council following the country’s fi rst elections in 1958-59 and was elected chief minister following fresh elections in 1960.

In 1961 Tanganyika was granted self-rule and Nyerere became its fi rst Prime Minister on December 9, 1961. A year later Nyerere was elected president of Tanganyika when it became a republic. In 1964, Tanganyika became politically united with Zanzibar and was renamed Tanzania. In 1965, a one-party election returned Nyerere to power.

Leaving power

In 1985, after more than two decades at the helm, he relinquished power to his hand-picked successor Ali Hassan Mwinyi. Nyerere left Tanzania as one of the poorest, least developed, and most foreign aiddependent countries in the world. He remained the chairman of the Chama Cha Mapinduzi. He died of leukemia in London in 1999. In 2009, Nyerere was named “World Hero of Social Justice” by Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann a UN diplomat. He received honorary degrees from several universities.