11 million Ugandans risk contracting sleeping sickness

Health experts have expressed fear of a possible merger of two forms of sleeping sickness, pausing challenges in diagnosis and treatment.

By Gladys Kalibbala

Health experts have expressed fear of a possible merger of two forms of sleeping sickness, pausing challenges in diagnosis and treatment. They say about 11 million Ugandans are at risk of contracting the disease.

Uganda is the first African country with the two forms of sleeping sickness; Gambiense and Rhodesiense.

Sleeping sickness (nagana in animals), also known as the Human African Trypanosomiasis, is transmitted by the tsetse fly, which harbours the trypanosome parasite.

Gambiense is dominant in north-western Uganda and Rhodesiense in the south-eastern region.

Gambiense got the name after it was first sighted in Gambia. It is chronic and common in Gambia, Central African Republic, DR Congo, South Sudan and some countries in West Africa.

Rhodesiense, on the other hand, is acute and is existent in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Malawi and Mozambique, among other counties in eastern Africa.

According to research by the health and agriculture ministries, since 1998, Rhodesiense has extended northwards to the districts of Soroti, Kaberamaido, Lira, Dokolo and recently, Kole.

Gambiense

According to Dr. Abbas Kakembo, formerly the in-charge of the Sleeping Sickness Programme at the health ministry, a patient can suffer from this chronic strain from the first day up to three years. In its second stage, which is after a year, the parasite develops and multiplies inside the body.

Thereafter, it penetrates the central nervous system, destroying the brain cells and causing mental illness.” After the mental breakdown, the patient can progress into a coma and eventually die.

Rhodesiense

With this acute form, a patient may die between six months and a year if not treated. In its second stage, the patient may also develop a mental problem then progress into coma and eventually die.

Treatment

A patient requires about $300 (sh733,500) for about 30 days. In addition, the patient must be hospitalised during treatment.

Dr. Charles Wamboga, the programme manager in charge of Sleeping Sickness Control, Ministry of Health, says treatment for both forms is different.

According to records, over the past year, over 300 cases of sleeping sickness were diagnosed and others died without reporting to hospital, claiming it was witchcraft.

Fear of merger

Wamboga says Rhodesiense and Gambience were apart by 150km in 2005, but the distance has since reduced to about 100km or less.

“We urgently need to improve the existing sleeping sickness guidelines,” he says. Following fear of the merger of both strains, the health ministry has put in place screening facilities at Lwala Hospital in Kaberamaido district to establish what type of sleeping sickness each patient is suffering from.

Diagnosis

Wamboga says patients are subjected to a lumber puncture (spinal tap), where fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord is drawn. “We examine the cerebral spinal fluids to determine whether the disease is at the first stage or has progressed to the second stage (when it crosses to the brain),” he explains.

Proper diagnosis is essential, as both the first stages and second stage are treated with different drugs.

Given their shape, sleeping sickness parasites are easy to identify. In addition, they stay outside the red blood cells unlike malaria parasites, which keep inside the red blood cells.

Once confirmed, the patient must be hospitalised between 10 to 30 days, while on treatment, which may include intravenous infusion every after six hours, according to Wamboga.

Diagnosis and treatment require skilled medical personnel as well as good laboratory services.

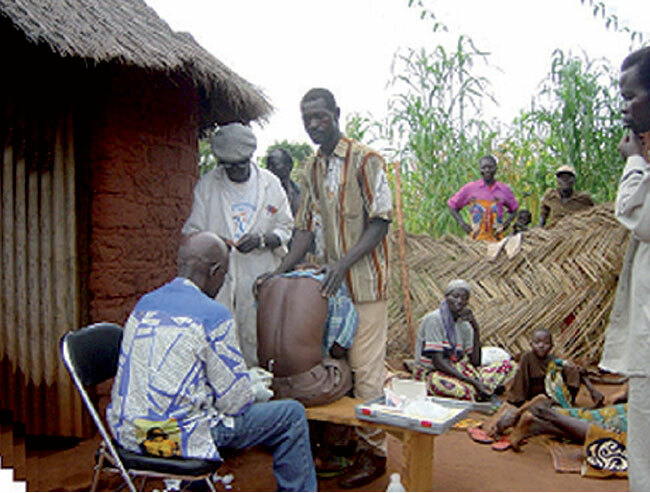

A medical worker extracts fluid from the spine of a sleeping sickness patient in Paliisa district.

What is fuelling the spread?

Dr. Dawson Mbulamberi, the assistant commissioner for Neglected Tropical Diseases at the health ministry, attributes the spread of the disease to the lucrative cattle business in the infested regions.

“Unless all these animals are treated before they are sold, we are doomed,” he says, adding that district local council members are already being sensitised.

The disease has also been fuelled by patients who escape from hospitals.According to Matilda Okitoi, a senior nursing officer at National Livestock Resources Research Institute in Tororo district, some patients run away from the hospital after starting on treatment, claiming the medication is so painful.

Lasting solution

Fredrick Luyimbazi, the assistant commissioner, Entomology (tsetse) in the Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries, says aerial spraying would wipe out the flies. “We are working on arrangements to conduct aerial spraying like it was done in Botswana, Ghana, Namibia and Zambia — countries which have wiped out the tsetse flies,” he reveals.

Luyimbazi says the spraying will be done using an environmentally safe chemical known as pyrethroids, an insecticide which is non-residual and bio-degradable. “The exercise would be performed by experienced pilots using computerised planes,” he explains. The ministry has also provided tsetse traps and pour-on insecticide in 16 districts.

Prevalence

The World Health Organisation’s reports indicate that tsetse flies are found in 37 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, putting 60 million people at risk. It affects between 50,000 to 70,000 people each year.

The disease, which was nearly eliminated in the 1960s has made a comeback due to war, population movements and the collapse of health systems over the past two decades.

Specific figures on prevalence are not available because of limited research and national surveys, but the disease has plagued much of the West Nile and Teso regions.

The affected districts include Soroti, Kaberamaido, Dokolo, Lira, Apac, Arua, Yumbe, Moyo, Maracha, Koboko, and Adjumani). Others are Bugiri, Kamuli, Iganga, Mayuge, Busembatya, Namutumba, Jinja, Buikwe, Buvuma and Kalangala Islands as well as Mukono.

Who is at risk?

Mostly the reproductive age group (15 to 45 years) are at higher risk. However, children are also at prone to infection because they are defenceless and tend to hang onto their mothers’ backs as they dig or collect firewood in the bushes.

Prevention

Health experts recommend clearing of bushes in infested areas, spraying livestock with insecticide as well as aerial spraying. According to Luyimbazi, aerial spraying costs about $400 (sh978,000) per square kilometre for the 160,000sq km that are infested.

Tsetse flies mostly reside in a weed called lantana camara, commonly known as kapanga. However, according to experts, the habitat depends on the species.

Tsetse flies are mainly found in vegetation by water bodies, in gallery-forests and vast stretches of wooded savannah where they get in contact with man, cattle and wild animals. Presence of people, tsetse flies and animals at water sources such as springs increase the risks of disease transmission.

Symptoms

General symptoms include intermittent fever, not responding to anti-malarials, loss of appetite, headache, joint pains, disturbed sleep, weight loss, body itching, swollen lymph nodes, swelling of face or ankles, fits and tremours, confusion, loss of memory and total apathy or coma.

First stage sleeping sickness presents like malaria with symptoms such as fever and weakness. Doctors say this stage is difficult to diagnose, but is relatively easy to treat. If no treatment is given, the parasite invades the central nervous system and the second stage subsequently sets in.

“This stage may be characterised by confusion, violent behaviour or convulsions. Named after one of its most striking symptoms, patients with sleeping sickness experience an inability to sleep during the night, but are overcome by sleep during the day. If left untreated, the disease inevitably leads to coma and eventually death,” Mbulamberi says.

Medical research shows that at first the trypanosomes (parasites) multiply in subcutaneous tissues, blood and lymph. This forms the first stage of the disease, known as a haemolymphatic phase, which entails bouts of fever, headaches, joint pains and itching.

With time, the parasites cross the blood-brain barrier to infect the central nervous system.

The second stage, known as the neurological phase, begins when the parasite crosses the blood-brain barrier and invades the central nervous system. Generally, this is when the signs and symptoms of the disease appear.

Doctors warn that disturbance of the sleep cycle, which gives the disease its name, is an important feature of the second stage of the disease and without treatment, sleeping sickness is fatal.

Treatment centres

The health ministry set up free treatment at Namungalwe in Namutumba, Mayuge, Luwuka, Kiyunga, Buikwe health centres and Iganga, Yumbe, Moyo and Adjumani hospitals.