What lies ahead for Uganda's 1st female DPP?

If I can leave a footprint, let me have people who deserve to be in prison be in jail and get the innocent ones out.

Jane Frances Abodo, the new Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), has never paid a coin for her education. From primary school to A'level, she was a scholarship student.

When she was admitted to university in 1993, it was on Government sponsorship. In 2015, she applied and got a scholarship from the Irish Embassy to pursue a master's degree.

She is the first female DPP in Uganda. That, however, does not mean her life has been a smooth ride. Coming from a humble home, in a society where education was a preserve for boys and escaping abduction by the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) rebels, there was one challenge after another.

The journey Abodo was raised in a small village in Kangole, Napak district, which was previously part of Moroto in Karamoja.

"It is home," she stresses.

Abodo attended Kangole Girls' Primary School, a missionary school at the time. Just like most girls in school at the time, they were there for the food, especially during the dry season, because school was a preserve of the boys.

However, the harvest season would see the schools almost empty. The Verona Sisters used to get the children sponsors from Canada and Italy.

Abodo had a family pick her and pay for her education until Primary Seven. Because her performance was excellent, she was again picked up by a priest and enrolled at St Mary's College Aboke, another missionary school, where she completed her O'level during the LRA war.

Towards exams, the rebels struck.

Abodo escaped being abducted. She recalls holding onto a friend who had been grabbed by rebels, but she had to let go to survive.

One hundred students were later released by the rebels, 30 were taken and some have never come back.

The survivors camped in Lira to wait for exams. They were guarded by the army as they sat their finals.

They barely had time to prepare, but about eight students, including Abodo, performed excellently.

Their headteacher tried to enroll the girls who had excelled into Mt. St. Mary's Namagunga, but all the slots were taken.

Luckily, Trinity College Nabbingo took them on.

A radio call was sent to her parish priest at home to inform Abodo of her admission. She hopped onto a lorry with her younger brother to Soroti, then took a bus to Kampala for the first time.

They made their way to Nsambya, where their sister's friend, who had trained as a teacher at Kyambogo, lived. She took them in.

Abodo had to walk from Nsambya to Nabbingo to pick her admission letter. They had to ask for directions while being pounded by the rain, but they made it there.

She asked their host to introduce her to a Jesuit priest in Nsambya and was led to Father Trudeau, who was passionate about helping children from Karamoja.

After he welcomed them and listened to her story, including the fact that she did not have fees, he took them to the city, where he paid her tuition and bought her scholastic materials, before taking them back to their host.

Father Trudeau would continue to pay Abodo's school fees for A'level at Nabbingo.

She excelled in her studies and was admitted to Makerere University on government scholarship to study Library and Information Science.

Abodo had not applied for law, but during chats with her colleagues in the first weeks of university, she was informed that with her exceptional performance, she could study law.

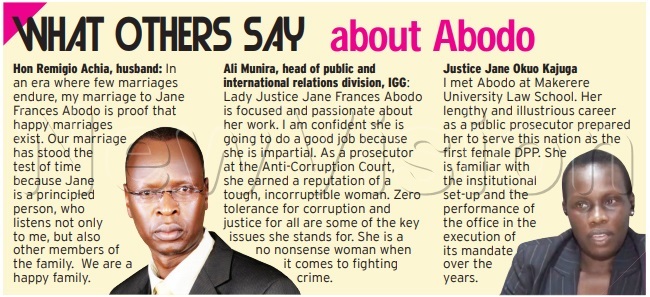

She consulted other students from Karamoja who had been admitted to the university. There were two Karimojong girls and five boys, including Remigio Achia, who would later become her husband. Achia went with her to meet the academic registrar, Prof. Huyha Mukwanason, for guidance.

Abodo did not understand what the course would entail but was instructed to report immediately to the faculty of law. She did the three years, then joined the Law Development Centre.

When she left school, she applied to work in the DPP's office in 1999.

The new office Abodo replaces Justice Mike Chibita, who was appointed to the Supreme Court.

The new office

She will have to deliver justice in a domain where corruption prevails. Uganda is ranked the 43rd most corrupt country out of 180 nations graded by Transparency International.

Lately, President Yoweri Museveni has been taking steps to tackle corruption. Last year, he held the walk against corruption and also created the State House AntiCorruption Unit.

So, Abodo's tenure comes at a time when expectations to end corruption and ensure justice are high. "It is easy to fight crime, all you need is to have focus, knowledge and a plan," Abodo says.

She was a prosecutor for 19 years and judge for two. She understands the system and knows the loopholes. "Court documents must be drafted well and charges well-framed.

Ideally, we need a prosecutors' academy to re-skill them on how to draft committal papers," she observes.

"We have retired prosecutors and judges, who are a resource and can provide excellent training. Fighting crime is going to be a challenge but I intend to share ideas and embrace people's opinions," she states.

"We have many unresolved murders. There should be more focus to have cases of murder properly investigated by a dedicated team of prosecutors, investigators and forensics working together as a team to get to the root," she says.

Abodo has served as a lawyer and a judge in the Criminal Division.

"When I was appointed to this job (on April 2, 2020), I told God: "If you know I am not going to manage it, please don't give it to me, but if you give it to me, then I will know that I will manage,'" she says.

"I am not under any illusion that it is an easy job. It is going to be tough, people are expecting so much and I am either going to set a precedent to have another female DPP, or never. It is important what precedent I set. I want to take each day as an opportunity to make a difference in people's lives," she adds.

Abodo says working as a judge for two years prepared her for this office. Important in her tenure is that the decision to charge should be taken cautiously. "I saw people that shouldn't have been charged.

I will weed the system of under-serving cases," she says. Abodo says cases of criminal trespass, which are land issues, are civil, not criminal. People prefer criminal cases because it is quick; people are arrested and taken to jail.

"There are cases of obtaining money by false pretense. These are just contracts gone sour. What are they doing in the criminal system?

If I can leave a footprint, let me have people who deserve to be in prison be in jail and get the innocent ones out," she says. Justice for women Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) is widespread in the country and requires special attention.

EACH DAY IS AN OPPORTUNITY TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE

About 50% of women aged 15-49 years, experience intimate partner physical and (or) sexual violence, at least once in their life time, according to the 2016 Uganda Demographic and Health survey.

"Women have the law," she says, adding, "We only need to change how it is applied, as well as the procedures of handling cases which come into the system."

The Police must work within deadlines while handling SGBV cases so that they are successfully prosecuted, she states.

"When a woman is raped, she is asked to testify and relive the experience six years later, which is hard. She would have already put the experience at the back of her mind, the witnesses may have died or changed location, and you can't get them," Abodo says.

She says there is need to fast-track SGBV cases. "Even though there is no special court for it, special procedures with timelines should be in place," she adds.

Abodo specifies that the period the Police, DPP's office, and court handle cases should be shorter.

The Police must have a conducive (private) environment to take statements, not the usual crowded rooms, full of men, she explains.

And there must be gender balance among its personnel to get quality evidence from victims with dignity, she adds. Also, prosecutors should be able to counsel. "We need social workers in the system.

It's not just enough to have a law degree, we need the relevant extra qualifications. Next time we are recruiting state attorneys, we need to ask besides the law degree, what other training they have. Counseling and law is a good mix," says Abodo.

Counseling and compassion will ease the fear of not being believed, which is always there, because offenders are always close relations like fathers, uncles or neighbours.

The law is available for women but the trouble is in the processes, she stresses. Ideally, we would have an SGBV court or specialised processes to handle cases. "The DPP has a mandate to manage investigations. We have a department dealing with SGBV with prosecution's guidance.

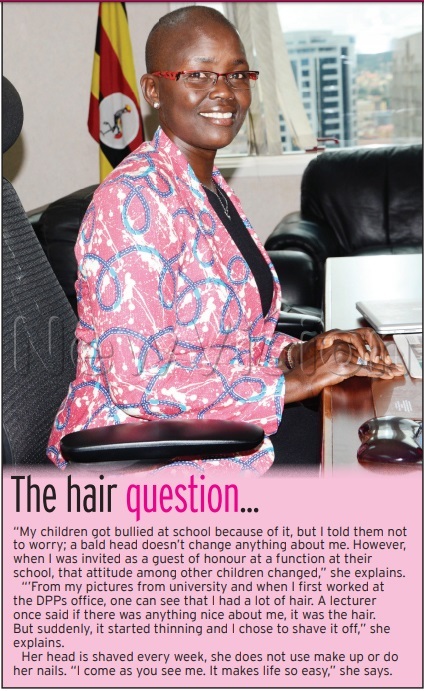

The Judiciary is weighing in on having specialised processes or an SGBV court," says Abodo. On being principled and focused "I owe it to my mother. She raised us with minimal resources and we were content with what we had.

Through her, I learnt that hardwork pays and there are no shortcuts. I work with dedication, give it my best shot and I am happy at the end of the day. Not because I want to be noticed, but because it rewards me," Abodo says.

"I am aware that there will be people who will want to bring me down, but I am focused, as long as I can defend my decisions. I am mindful of the legacy I will leave behind," she says. At every opportunity, Abodo mentors young people. "I don't wait for gatherings.

Mentoring should be instantaneous and continuous whenever an opportunity arises. Just two minutes will make an impact," she observes.

Balancing family and work Remegio Achia, the MP for Pian in Nakapiripirit district, was her university sweetheart.

They met in first year and eventually got married. They have two children, a 20-year old son and a 16-year-old daughter. It was tough for Abodo at the beginning of her career at the DPP's office.

"My children were very young and I had to drop and pick them from school daily. One day, because of work demands, I picked them at 8:00pm. I felt bad and vowed to do better," she says.

The trips to and from school were the time they bonded as a family. By the time she was made judge, things had become easier.

"My husband is a politician and stays in the village most of the time and the children are in school. But when they are around, I cook for my husband and serve him myself. Cooking is one of my hobbies," says Abodo.