Trafficked Karimojong girls end up with Al-Shabaab

A Vision Group investigation has established that some Karimojong girls have reportedly ended up in Somalia, in the hands of the Al-Shabaab, with hardly any hope of returning home.

TRAFFICKING

Karimojong girls as young as 10 are being trafficked from Napak district into Kenya's capital Nairobi. A Vision Group investigation has established that some have reportedly ended up in Somalia, in the hands of the Al-Shabaab, with hardly any hope of returning home.

_________________________

It is about 8:00am when we hit Ocorimongin market in Katakwi district. This is where we had been told teenage Karimojong girls are sold to agents who connive with traffickers and sell them to the Al-Shabaab in Somalia. The market is busy, but the girls are nowhere.

Margaret (not real name) says the traffickers have since changed their recruitment tactics following Government's intervention last year, where officials threatened arrest of parents who sell their children.

"The agents no longer come to the market. They go to the villages and negotiate with the parents," she says.

"Do you know where we can find young Karimojong girls to work as housemaids across the border?" we ask a woman selling clothes.

"I wish you had come earlier. I have four girls, but I have just sent them back to their homes to pick a few clothes. When do you want them?" she asks, before revealing that she got the girls from Abarata Kere, a market in Usuk county.

We promise to return on the following market day to negotiate and close the deal.

Junior, a vendor who speaks to us in Luganda, confesses that the vice is still going on in Arapai Market, Soroti district.

The busy Ocorimongin weekly market in Katakwi district

The busy Ocorimongin weekly market in Katakwi district

The Friday market attracts vendors from as far as Busia and Kampala

The Friday market attracts vendors from as far as Busia and Kampala

In July this year, Apio (not real name) left her home in Iriiri sub-county, Napak district in search of ‘greener pastures'. This was after her mother handed her over to a woman who promised to get her a job.

Five months down the road, Apio's exact destination remains unknown. However, from our interactions with some people at the market, she could have been trafficked across the border.

Several girls from Karamoja are working as housemaids for the Somali community in Kenya's capital Nairobi.

Girls as young as 10 are engaged in domestic work and are reportedly paid as little as Ksh1,000 (sh36,000) per month. Some are said to be mistreated, while others sleep out in the cold.

Girls in Nairobi

Karimojong girls in one of the slums of Nairobi

Karimojong girls in one of the slums of Nairobi

At a distinct location in one of Nairobi's constituencies, an unusual negotiation is taking place over lunch in a busy makeshift restaurant. Seated across crowded tables are two girls, one of them bubbly and appearing unbothered by the largely male presence dining around them in sharp contrast to her colleague, who appears nervous as she pushes down a mouthful of ugali (maize meal) with piping hot fish soup.

Seated on the opposite end of the table, we are posturing as newcomers in the area who want to employ young girls to work as housemaids. The girls believe we are here for exactly that. A couple of minutes before, our conspicuous interaction had started off, with us making our intentions clear in English.

The girls having lunch in a makeshift restaurant in Nairobi

The girls having lunch in a makeshift restaurant in Nairobi

Mary (not real name) is the livelier of the teenage duo and has a comb sticking through her short hair, which embodies her confidence. Without hesitation, she tells us that the kind of girls we want are available, but she is keen to underline that they would not work for less than Ksh8,000 (sh290,000).

A few feet away, the rest of the group, after having their lunch with us and making way for other patrons to dine in the packed facility, are huddled in a corner, awaiting the outcome of the negotiations.

Their patience is punctuated with audible, but indistinct interaction over perhaps who might get lucky to be chosen for work. They seem eager. There are about seven of them in the company of three older females, including our undercover source.

The girls, some of whom have come along with bags, look to be in their teens.

While the negotiation took place in the restaurant, the rest of the girls stood nearby awaiting the outcome of the interface

While the negotiation took place in the restaurant, the rest of the girls stood nearby awaiting the outcome of the interface

Back on the table, we get into the thick and thin of the negotiation, asking Mary and her mate to lower the price. Ksh8,000 is on the high end for us, we tell them. Our storyline is that we are less than a month old in the area and want young housemaids, preferably aged 13, 14 or 15 years.

Suddenly, they realise we speak Luganda, thanks to what we had thought was a whisper between us on the sidelines of the engagement. English is immediately dropped, and the girls break into fairly good Luganda. We immediately learn that they are from Karamoja.

Mary insists she is 19 and her mate, 18, but like the rest of the group, they look younger and seem keener on working than anything else. The two girls doing the talking decide to cut the price down to Ksh7,000 (sh255,000) only because we are from Uganda. Mary says, in contrast, they are usually paid over Ksh13,000 (sh400,000) by Somali employers in Kenya.

Later, our source would tell us that it is highly unlikely and that majority of the girls settle for as low as Ksh3,000 (sh108,000). Here, Mary and her friend will not go below Ksh6,000 (sh217,000). While they claim they also work as housemaids, they also act as the link between potential employers and girls.

Buying housemaids: The two girls that we engaged in the negotiation

Buying housemaids: The two girls that we engaged in the negotiation

During the negotiation, they keep consulting each other in a familiar language (Ng'akarimojong), before turning their attention back to us in a blend of English, Luganda and Kiswahili.

Here is how it works. The broker connects the potential employer with the desired girl. Depending on the terms agreed, every month, the employer sends the housemaid's salary to the broker, who then gets his/her cut, before reportedly giving the rest to the girl.

So what percentage of the lump sum, say Ksh3000 (sh108,000), does the recruited housemaid get? we ask.

This is a question Mary and her friend keep dodging during our interface. Their tactical evasion of this question in our covert inquest provides us with a rough conviction that this is familiar territory. They seem trained on how to dodge such questions. After bringing up the subject about five times, we fail to get a response.

Some of the trafficked girls we met came carrying backpacks

Some of the trafficked girls we met came carrying backpacks

From an independent source, we established that the money one girl takes home after the broker's cut is Ksh1000 (sh36,000).

About an hour into the negotiation, we begin to sense their unease over this arrangement. We suspect their growing impatience may have tickled their suspicion. The initially lively Mary has now withdrawn and keeps whispering to her friend in Ng'akarimojong.

We decide to cut the negotiation short and promise to meet again in the following days to finalise the deal.

Trafficking

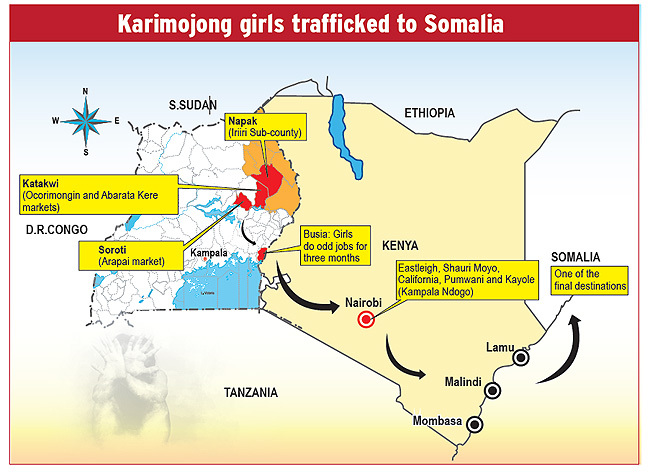

After parting ways, our informant reveals to us that every day, at least 10 girls are ferried into Kenya. They are destined for specific locations in Nairobi or transported to other locations, including Somalia.

A source who has witnessed girls trafficked into Nairobi says many are being driven into Nairobi on trucks.

A few minutes later, our source receives a call that a group of girls had just been ferried into Nairobi.

A few days before our meeting with the girls, we chanced on a video footage showing a group of four young girls with backpacks in the company of a veiled woman leading them into a building.

Young Karimojong girls being led into a building in Nairobi. (Credit: Counter Human Trafficking Trust-East Africa)

Young Karimojong girls being led into a building in Nairobi. (Credit: Counter Human Trafficking Trust-East Africa)

The amateur video provided to us by Counter Human Trafficking Trust-East Africa, a Kenyan non-governmental organisation (NGO), shows two of the girls having their heads covered on a busy street. Their fate is not known.

"Thousands are being dropped off by lorries typically in the dead of the night. They are so many that they even sleep in the open in the areas of Shauri Moyo and Eastleigh in Nairobi, which are predominantly occupied by the Somali community," says Mutuku Nguli, the chief executive of the NGO. Apart from Eastleigh, also known as ‘Little Mogadishu', the Karimojong girls are known to occupy California, Pumwani, Majengo, Pangani (Chai road) and Kayole (Kampala Ndogo).

"These are young girls aged 10-14," Nguli says. "When they are connected to the Somalis, they eventually connect them to Somalia." Adding that it is a lucrative business for them (Somalis)." Nguli says the girls have diversified into prostitution, bar tenders and massage parlour services.

"Reports are rife of cases of murder and abuse during their employment in Eastleigh, but all this goes unreported to authorities. It is alleged that their employers go to great length to cover up such cases," he says.

Once, a 13-year-old girl, working as a housemaid, is said to have testified to have been slapped hard by her employer that she developed a hearing problem and the earing she was wearing at the time sunk into her skin. Unable to cope, she quit.

Some girls are said to have transited to the Middle East, while others are reported to have travelled south to the Kenyan coast, where they work in brothels and other low paying service sectors.

Our sources say a lot of exploitation takes place under the guise of domestic employment. While Kenyan domestic workers cannot accept less than sh5,000 (sh180,000) per month, trafficked Karimojong girls settle for as low as Ksh1,000 (sh36,000).

The degree of their vulnerability is intensified by the recurrent pressure to send part of the money they earn back home to their families.

Another source reveals that some of the girls are transiting towards Somalia, with a potential destination being Al-Shabaab brides. The main route has been mapped through Mombasa- Malindi-Lamu, before crossing into Somalia at Kiunga border.

Kenya a transit route

Kenya is a source, transit and destination when it comes to trafficking, says David Gitau, who works in the directorate of criminal investigations of Kenya's Anti-Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Unit.

He says Ugandans are the third most trafficked nationals through Kenya after Nepal and India. Others include Rwandans, Ethiopians, South Sudanese and Burundians.

There is also reported widespread use of Asian women employed to work in mujra dance clubs and brothels in Nairobi and Mombasa.

Ethiopians are trafficked through Nairobi all the way to South Africa and along the way, some are exploited.

According to Gitau, young girls and boys are recruited to join criminal and terror networks in Somalia and Libya.

He adds that several Ugandan girls have previously been rescued from domestic work, placed in safe shelters, before being repatriated back home.

Victims of trafficking, he observes, are often absorbed into high-risk sectors, including tourism, hospitality and labour export for forced labour and sexual exploitation.

The beguiling Moru Atanangito in Napak district in Karamoja. Many girls are trafficked from this area

The beguiling Moru Atanangito in Napak district in Karamoja. Many girls are trafficked from this area

Why Karimojong girls

Mutuku Nguli says Karamoja is one of the poorest parts of Uganda and this has rendered the girls vulnerable.

Nguli says the girls, once recruited, remain loyal and will continue working even when they are underpaid and mistreated.

Lt. Col. Charles Imbiakha, the spokesperson of the AMISOM force, says they are aware that the Al-Shabaab are using women as suicide bombers.

Moses Binoga, the coordinator of the anti-human trafficking taskforce at the internal affairs ministry, when contacted, downplayed the plight of trafficking Karimojong girls.

He said the information received so far is from an NGO, which they have since tasked with developing "concrete information" on the matter.

Moses Binoga said seeing a Karimojong girl on the streets of Nairobi does not mean they have been trafficked

Moses Binoga said seeing a Karimojong girl on the streets of Nairobi does not mean they have been trafficked

Binoga adds that the Government will embark on a verification process to ascertain whether the girls in question are victims of trafficking, before making any rescue arrangements.

"By the way, seeing a Karimojong girl on the streets of Nairobi does not mean they have been trafficked. And, of course, you also know that there are some tribes in Kenya that share characteristics with the Karimojong," he points out.

Meanwhile, Peace Mutuuzo, the state minister for gender and culture, says the ministry is monitoring the situation to ensure that the gaps are covered.

"They are using Busia and Tororo routes. When you meet most of them at the border, they pretend to be sorting rice and beans, but they are in transit."

Mutuuzo says they have constituted a team and are holding cross-border meetings to discuss the matter.

To scale down on human trafficking, she says the gender ministry has deregistered some 600 recruitment agencies, whose scope of work was deemed questionable.

How Kenya is combating the vice

Grace Girambu, the head of Kenya's Anti-Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse Unit, says while there is internal trafficking in the country, the number of girls trafficked to the Middle East has scaled down in the last two years.

She says in 2017, Kenya signed a memorandum of understanding with several countries in the Middle East to formalise the export of labour.

Kenya also created the National Employment Authority (NEA), as well as training centres, where girls seeking to work abroad are equipped with skills on how to handle various tasks. Once the agencies take them on, they are given certificates.

NEA also formulated a biodata system, where one's details are documented and one of the agreements given to the employment agencies is to ensure that the girls have their phones and passports at all times.

Way forward

While trafficking remains a challenge across the East African region and beyond, experts have proposed several interventions that will help curb the vice. One of them is targeted awareness campaigns to vulnerable communities and businesses, particularly in the tourism and hospitality sector.

There is need for countries to develop a national threat assessment to better understand the scope and scale of trafficking, as well as strengthening border control and combat transnational human trafficking networks.

Damon Wamara, the country director of Dwelling Places, a Christian NGO involved in rescuing, rehabilitating, resettling and reconciling vulnerable children, says a holistic approach is needed to deal with trafficking.

He says the people of Karamoja should be provided with better services, such as health and education, as well as invest in agriculture in order to empower the region.

Wamara says learning from survivors of human trafficking is key to shaping policy and changing attitudes on human trafficking.

Nguli says: "The Government should consider constructing boarding schools for the girls. The schools should provide food, clothes and co-curricular activities, which will change their mindset."

He adds: Vocational institutions can be set up to skill and empower those out of school to fend for themselves.

Restoring hope

Lobong, who previously tried out life on the streets of Kampala, is now a thriving farmer back home in Napak district

Lobong, who previously tried out life on the streets of Kampala, is now a thriving farmer back home in Napak district

Poverty and conflict are some of the push factors behind the movement of persons from especially rural to urban areas in search of a better life. An improved life is what Charles Opio Lobong hoped for his family when they left their village in Napak for Kampala in 2004, only to be rudely awakened by life in a slum setting.

Lobong, now 39, followed his wife and eight children to Kampala, where he ended up selling rat traps and doormats for a living in Kisenyi and Katwe, city slums.

To make ends meet, Lobong surrendered his children to the streets to beg, all the while sleeping on verandahs, battered by the elements. They eventually started renting a room for sh1000 a night yet life continued to hit them hard.

"Sometimes, my wife, like other women living on the streets, would pick food dumped in dustbins to feed us," he says, adding they depended mostly on the money his children collected from begging. Technically, children were the breadwinners.

Lobong's experience is similar to Veronika Lokuda, who currently lives in Nabokat-Atumuchoke village in Iriiri sub-county, Napak.

The 74-year-old also tried to use her three children to earn a living on the streets of Kampala, until the day she lost one child in a hit-and-run car accident.

"My child was crashed beyond recognition and when I was called to the scene, I could only identify the cloth she had worn that day," she says. That was her turning point.

Lokuda decided to leave the streets of Kampala when she lost one of her children in a hit-and-run accident

Lokuda decided to leave the streets of Kampala when she lost one of her children in a hit-and-run accident

In 2008, officials of gender ministry and Dwelling Places moved through Katwe, asking the street people who wanted to be returned to their homes to come forth.

Lobong and Lokuda right away decided to move back to Karamoja with their families.

They were resettled in a camp and were provided with startup kits. Eventually, they obtained land and began to rebuild their lives.

Lobong, who is now the LC one chairman of Nabokat-Atumuchoke village, boasts 30 acres of land, on which he grows a variety of crops, including bananas, yams, cassava, sorghum, maize, sesame, pumpkin, etc.

Lobong is currently the LC 1 chairman of Nabokat-Atumuchoke village

Lobong is currently the LC 1 chairman of Nabokat-Atumuchoke village

Lokuda, who lost her right hand during the conflict in her area back in the day, now sells sacks of sorghum to nearby markets.

When they returned to Karamoja in 2018, Dwelling Places enrolled all children aged from five years to Kapuat Primary School, a boarding school, and supported them to stay in school.

Besides education, the communities of Napak were also retooled with saving skills. Lobong says that with the support of Dwelling Places, they formed 28-member groups to receive sh3m as capital for income-generating activities.

His group chose cereal banking as a venture and today, they are selling sorghum and sunflower to the Soroti market. "Our store is doing well," he says.

Also, after adopting the idea of village savings and credit loans schemes, members can now get loans from the group SACCOS.

If Apio got to know about Lobong and Lokuda's experience, her world would be completely different and better than what it is now.

[The article was done in collaboration with the Democratic Governance Facility (DGF)]

Get involved

spotlight@newvision.co.ug

0414337452