The death of the bus in Kampala

As the buses collapsed, individual entrepreneurs started trying out minibuses on city routes to meet the demand for transport.

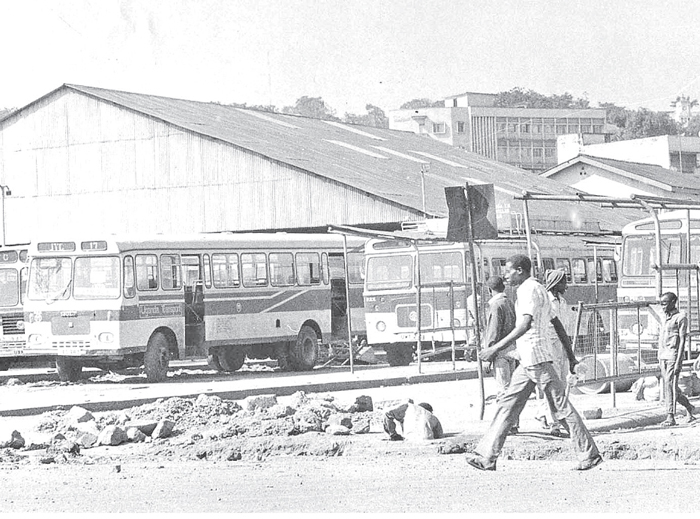

The taxi park of the 1970s

By Joachim Buwembo

KAMPALA UNITY INDEPENDENCE SHARED SPACE

One of the most drastic changes in Kampala's life after the economic disruption that started in 1972 was the death of the bus as the basic means of public transport.

Like any modern city, Kampala had a passenger bus service that workers and schoolchildren used daily as a matter routine. The bus service was run by Uganda Transport Company (UTC), whose brand colours were green and gold.

It is difficult to describe the Kampala public transport of UTC buses to somebody who has not been to a city where buses work properly, but let us try with some examples:

|

Facts on Kampala etween the UTC terminal on Channel (now Ben Kiwanuka) Street and Mulago Hospital, there were ten buses (times two) moving in either direction at any given time. |

Overloading started and adherence to timetable slipped. It did not take long for the UTC to become dysfunctional as other public companies did, and the new enterprising spirit of Ugandans stepped in to fill the gap. The commuter ‘taxis' had always been small station wagons, the last dominant one being Peugeot 404 that sat eight passengers but they plied trunk roads, not the city.

As the buses collapsed, individual entrepreneurs started trying out minibuses on city routes to meet the demand for transport. Volkswagen Kombis were tried out, as were old Land Rovers apparently boarded off from the police.

Than Mercedes Benz, yes Mercedes Benz, 25 passenger minibuses almost took over from the mid-seventies. These were possibly the last brand-new PSV equipment on the city roads before the era of reconditioned Japanese vehicles set in during the second half of the seventies decade.

Used Nissan and Toyota commuters than became the basic means of public transport in Kampala, until today. Over the ensuing four decades, Uganda's taxi industry has developed to employ tens of thousands of people.

Kampala's deceptively rowdy transport subsector manned by apparently nasty, rude, unkempt drivers and conductors is paradoxically the country's most efficient economic sub-sector.

Relying upon a hundred per cent second-hand equipment, a woefully underdeveloped infrastructure/road network and a weak regulatory atmosphere, the industry serves the urban population with clockwork efficiency unheard of in most other sectors.

Most comparisons to the Kampala taxi industry would, in fact, appear unkind. Consider for example the ‘efficiency' of the public housing sector manned by sophisticated, highly educated professionals and a whole ministerial portfolio to ensure it enjoys cabinet policy attention, but only has lamentations to report whenever they have to report - citing millions of unit deficits to report year in year out.

What of the health sector where public facilities are like a death trap while private hospitals are some of the most ruthless capitalist machines? Hospitality industry which shows little tendency towards standardization leaving every unit to do things it's own way? Even the giant telecoms, if the government's recent complaints are anything to go by, are just, well, let us be nice and not say.

The UTC buses in the 1979s

The rudeness of Kampala's taxi-men is really a necessity for there trade-in the circumstances. It is not cultural, for they come from all corners of the country, though the north, for now, seems to be under-represented. There conduct is not characteristic of any tribe - it is Kampala's reality in this shared space. They need it to secure unhesitant compliance from the passengers as a way of ensuring they meet there daily revenue targets.

Those rowdy young men you see, operate in what could be the most self-regulated industry. Organised and supervised under ‘stages' or more accurately, routes, they have very strict operating codes and procedures. The fares chargeable are standardized even as they vary according to time of day, the density of traffic and even the weather.

There pricing is virtually similar to online airline tickets - minus computers. The manning of the vehicle is agreed upon with the owner who puts it in the fleet with the driver and conductor closely supervised by the stage management.

This management also runs the stage cooperative society (SACCO) which does a thorough job to ensure the members don't mess their personal finances, and things like children's school fees that disturb other professionals are well catered for.

Many of these stage SACCOs have branched into buying land for different purposes, including those relevant to there like petrol stations. A close look at the Kampala taxi industry can make you wish these fellows were in charge of some government departments.

But fascinating as the taxi industry may be, it is just an improvisation that has gone on for too long. In the general sense, it is not sustainable to have ten thousand old engines running across the crowded city of a poor country that imports all the fuel, dirty fuel at that. A modern city needs a hybrid public transport system and Kampala's transport master plan ought to address this.

With all major world vehicle manufacturers issuing their deadlines to stop producing fuel combustion engines (Volvo already stopped), consumers should also invoke their sovereignty and state deadlines for allowing pollutant vehicles and Kampala shouldn't be an exception.

Everything must be done to promote orderliness and minimize pollution in the city. To paraphrase the conservationists' maxim, Kampala does not belong to us; we borrowed it from the future generation. We need to return it to them in a decent state.