Will bNAbs yield a one size fits all HIV vaccine?

Therefore, the studies are considering the idea of using an antibody made by scientists and giving it to people directly, i.e. using an intravenous (IV) infusion, to prevent HIV infections.

Spain

MADRID-It has been 21 years now and still ongoing—research for the HIV vaccine. Researchers are now focusing on identifying a particular antibody type that can disarm the virus, by using the broadly neutralizing antibodies (bNAbs).

Speaking at the ongoing global scientific meeting in Spain, Madrid, which is dedicated exclusively to biomedical HIV prevention, Nyaradzo Mgodi, a scientist from the University of Zimbabwe explained that the human body has antibodies, which work to prevent infections or fight foreign bodies.

Consequently, there is ongoing research on how the antibodies can neutralize or ‘disarm' the virus.

The antibodies see the virus, bind to it, hence blocking entry into the body cell.

"We have cells in the body, known as CD4, they have receptors. These receptors are where HIV binds. However, the neutralizing antibodies, bind to the areas that HIV uses to attach to the cell. So the virus just becomes neutral, and gets cleaned out of the body.

"Without those antibodies, HIV binds to the receptors, gets into the cell, divides and disseminates," Nyaradzo adds.

Therefore, the studies are considering the idea of using an antibody made by scientists and giving it to people directly, i.e. using an intravenous (IV) infusion, to prevent HIV infections.

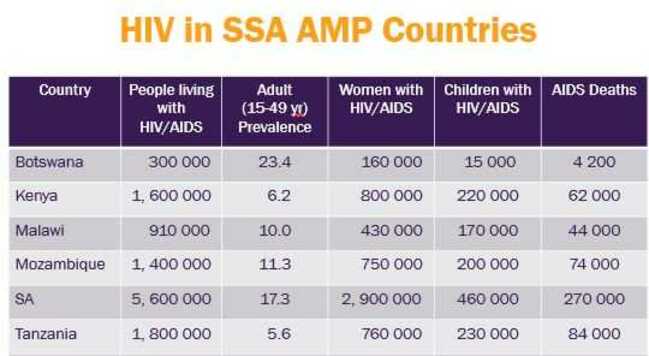

Currently, part of the bNabs study, is ongoing on among a group of women in sub Saharan Africa. "We recruited 1900 female participants from sub-Saharan Africa to take part in the study. We are doing it in Zimbabwe, Malawi, Botswana, Tanzania, Kenya and Mozambique," she explains.

Women in low and middle‐income countries still bear a disproportionate burden of the HIV/AIDS disease, which is the leading cause of death globally in women ages 15‐44

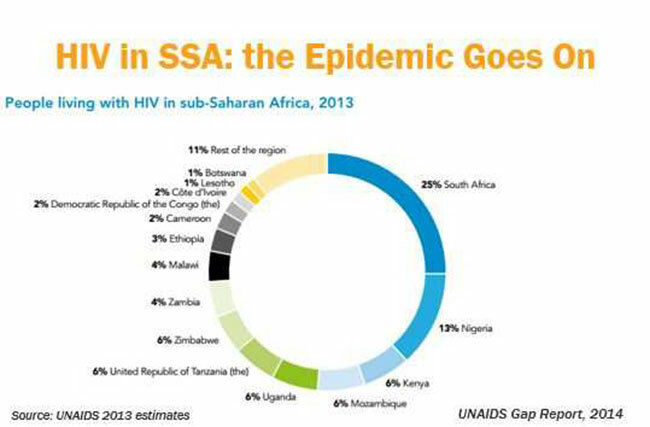

It exerts an especially high toll in sub‐Saharan Africa, where over half of the 24.7 million people living with HIV-1 infection in sub-Saharan Africa were women and young women are up to twice as likely to be infected as young men. In this sub-population, un-protected heterosexual intercourse is the leading mode of HIV-1 transmission.

The study is being conducted by two groups, the HIV Vaccine Trials Network and the HIV Prevention Trials Network. It is being funded by the National Institute of Health.

Nyaradzo emphasizes that this is not a vaccine but will contribute to vaccine development.

She continues that 24 months from now, we should start seeing results from the study and adds that the bNabs research is significant because despite many advances in prevention and treatment, the global HIV epidemic continues.

Millions of new HIV infections occur every year. The current prevention toolbox is insufficient to curb the epidemic.

"We cannot treat our way out of the epidemic," Nyaradzo Mgodi, a scientist from the University of Zimbabwe notes.

Furthermore, scientists have isolated bNAbs from people living with HIV who have been found to neutralize or disarm different strains of HIV. Most vaccines induce production of antibodies against pathogens; therefore, studying bNAbs can inform vaccine design.

However, Fred Mukasa Kibengo of Uganda Virus Research Institute is skeptical about the bNAbs that are being developed, regarding their effectiveness in the various sub types of HIV.

"bNAbs targeting a single sub type of HIV are not likely to work, and what is likely to work is to find bNabs responding to the different sub types," Kibengo says.

Nonetheless, Makerere University Walter Reed Project (MUWRP)'s Francis Kiweewa remains hopeful about the efficacy of bNAbs by siting an example of the current anti-retroviral therapy in use today.

"The first drugs ART drugs we are using today were tested on individuals with HIV sub type b, for example AZT. But these are the same drugs that are working for all the sub types now, so this keeps my hope in bNabs alive," Kiweewa notes.

"All these drugs were tested on patients in Africa, after having been proven to work in America, before they were rolled out to other places. And when rolled out to other areas, these drugs continued to work."

He notes that during the early studies, the sub type that the research targets may not be vital, since the key result needed is proof of concept, after which adjustments can be done where necessary to suit the different sub types.