The innocent victims of mothers' imprisonment

“Children growing up in prison take the prison environment to be normal and are under the influence of criminals. Embedded in criminality and despair, it is the infants who suffer."

PIC: With their babies strapped on the back, inmates of Luzira Women's Prison head to the Family of Africa daycare facility to receive their children's food. (Credit: Petride Mudoola)

INCARCERATION

The high walls of cold cement rise against the horizon as I approach the heavily manned facility. The walls present an imposing obstacle -- a clear turnoff for any inmate harbouring ideas of a prison break.

Welcome to Luzira Women's Prison, which some 500 women call home as they do their time.

But the country's largest female penitentiary accommodates more than just women. Their children, the forgotten and invisible victims of justice, are there too.

Every time I visit a female detention facility, my heart sinks for the innocent kids who are in prison because of the wrongdoing of their guilty parents.

The thought of a toddler being behind bars is, at best, odd. But considering that mothers and pregnant women find themselves locked up every now and then, women's prisons will continue keeping children.

While some are sent to prison while pregnant and give birth bars, others go to jail with their children. Children whose other family members are either unable or unwilling to take care of them end up in locked up with their convicted mothers.

Clad in the characteristic yellow Luzira prison uniform, inmates are ordered to "fall in" for a second head count. When the exercise begins, movement outside of the wards of residence is limited because everyone is required to stay where they are until the count is complete.

Bathed in the scorching sun, inmates squat in line as they wait for the second count. The ones with babies strap them on their backs while their counterparts with older children queue up with them tagged along.

Prison officials regularly update their superiors on the population of the inmates as well as the current situation inside the detention facility.

"Jambo [Hello] sir, we have unlocked 520 inmates and 31 children. The situation is normal." That is the officers manning Luzira Women Prison's gate as they salute their bosses superiors and assure them of safety, before ushering them in.

On average, inmates are counted at least three times a day -- in the morning, afternoon and evening before they are locked up for the night. But in cases where inmates are counted and figures don't add up, the counting is repeated to ensure the figures tally.

Having presented myself to the guards and gone through security checks within the female wing, I am referred to Family of Africa, a structure adjacent to the women's prison, where I meet beaming faces of children.

Welcome to the prison daycare centre.

Inside, the playroom is colourful and packed with toys and games for each of the children to enjoy. Dressed in their navy sports uniform, each of them scrambles to prove to me that they have the best toy.

Subtract the prison warders manning the gate from the equation and you would think it is an ordinary nursery school.

The prisons authority offers free daycare service to prisoners' children.

The daycare was constructed in 2005 by Italy-based Family of Africa, an NGO founded by Fr. Felix Sciannameo, to support children with a parent in prison.

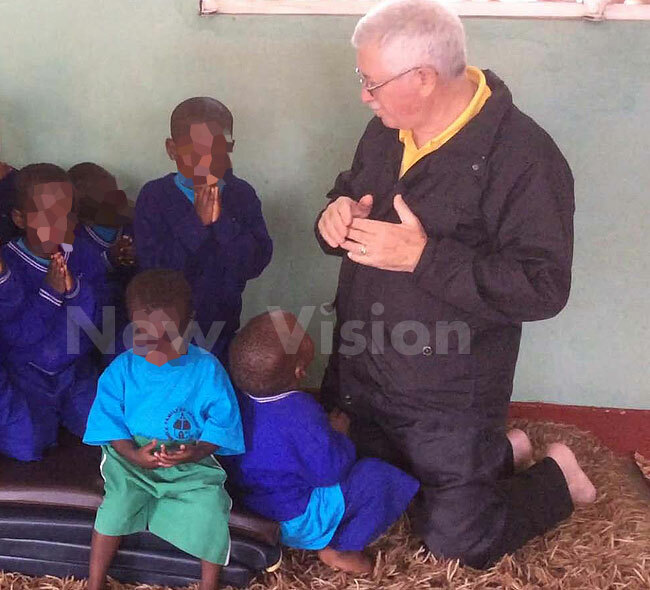

Fr. Sciannameo taking prisoners' children through a prayer before a meal. (Credit: Petride Mudoola)

During my visit, I meet a two-year-old girl, born in prison. She turns away and cries when I reach out to lift her.

"The baby is not used to visitors," her mother offers.

"She is used to only two colours -- the yellow uniform of the inmates and the khaki-brown uniform of prison warders. She has been here since she was born," the inmate who was convicted of arson, and prefers anonymity, says.

Fate

Frank Baine, the Uganda Prisons' publicist, says the children acclimatise to the detention environment.

"Children growing up in prison take the prison environment to be normal and are under the influence of criminals. Embedded in criminality and despair, it is the infants who suffer."

They are often considered as forgotten children and ignored victims of justice yet prison is not appropriate for children to live in. A jail can never provide a family environment which every child deserves, Baine adds.

"But many children find themselves incarcerated and some are born in prison purely by fate. These children find themselves in this situation because their mothers are in prison and have no-one else to take care of them while their mums serve prison sentences."

I find 31 children living with their mothers inside the facility. Some of such women, like 30-year-old Peace Nantumbwe, have two or more children with them in jail.

Serving a five-year sentence over obtaining money by false pretense, Nantumbwe had a two-year-old child and was three months pregnant at the time of her arrest. She recently gave birth to her second child.

She walks in soothing her two-day old baby as her older child waits in the corridor to meet her mother after a week-long wait.

Nantumbwe went into labor and had been referred to Mulago Hospital, where she delivered her baby and was brought back to the prison to heal and get postnatal care at the prison's maternity wing. She had to leave her first-born daughter at the daycare facility.

For now, the older child is in the safe hands of the daycare centre caretakers while her newly-born sibling stay with their mother in the maternity wing, which Natumbwe shares with other women.

"I left my daughter behind because there was no-one to take care of her in Mulago Hospital, where I had been referred to as I experienced labour pains," she says.

The daycare centre comprises three fenced off houses sitting on a lush expanse with a spectacular view of Kitintale and Bugolobi, in the outskirts of the city.

With babies strapped on their backs, female inmates are escorted by prison warders as they cross the road that separates the women's prison from the daycare centre.

Babies that are below one year old live in the prison cells with their mothers, but after clocking the age of one, they are brought to the daycare centre, where they are accommodated and are reunited with their mothers every Sunday.

Life inside the daycare

"Growing up in prison is traumatic to children, but it is often seen as the only option because separation from a parent is equally stressing, which is why we set up the daycare centre," says Fr. Sciannameo.

According to him, prisons do not provide an appropriate environment for babies and young children, yet if babies and children are forcibly separated from their mothers, they suffer permanent emotional and social damage.

"I felt that the children had a right to live the ordinary life of a child, but they were deprived of that right when they stayed with their mothers for 24 hours a day and listened to all sorts of negativity beyond their understanding," says Sciannameo.

Besides, it was exhausting for inmate mothers to carry their babies on the back all day long.

Italian priest Fr. Sciannameo approached friends back in his country, who funded construction of the daycare facility, of which the Ugandan government offered land for its construction on top of providing water and electricity.

There is also an arrangement in case of adoption.

"We cater for children with a parent in prison, but when it comes to fully adopting a child whose parent has been released but is not capable of taking care of them, we are required to seek a court order seeking legal guardianship of the child," he explains.

Despite the child-friendly environment that the daycare centre provides, Sciannameo, worries for the children's reintegration after they leave prison since back home, or elsewhere they may go, "life might be very different from what we are exposing them to".

"After they get used to this kind of environment, what happens when they get back to the society where this may not be available?"

At the facility, children are taken through elementary education. When they reach the age of three, they are taken to Biina Family of Africa Home or referred to different primary and secondary schools run by St James Catholic Church, before joining university.

Babra Tumusiime, a teacher at Luzira-based Family of Africa home, takes children of inmates through a mathematics lesson. (Credit: Petride Mudoola)

Fr. Sciannameo, however, prefers the children to go for vocational training courses, such as carpentry, building and construction, catering, mechanics, tailoring or hotel management because it is easier for them to find jobs with such skills.

Law on children

Meanwhile, Prisons' publicist Baine says there are resctrictions, but some children who were born in prison stay longer in cases where there is no-one back home to take care of them.

"Prison regulations restrict children above two years of age from staying with parents in prison for fear that they may be exposed to violence and use of abusive language that might adversely affect the psychological development of young children.

"Kids grow up in an environment where they see inmates fighting, abusing and constantly struggling for their surviva. The mothers feel their stay in jail would have a negative impact on the children's behavior, education and social life after their release from the prison," Baine explains.

UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners recommends that special accommodation be set up in women's prisons "for all necessary pre-natal and post-natal care and treatment" and that arrangements be made for children to be born in a hospital outside prison.

If a child is born in prison, this fact shall not be mentioned in the birth certificate, it adds.

Also, "a nursery staffed by qualified persons" should be provided in cases "where nursing infants are allowed to remain in the institution with their mothers", and that when the infants are not in their mothers' care, they will be placed in the nursery.

The Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners, amongst other provisions, recommends that prisoners' children be provided with an environment for their upbringing as close as possible to that of a child outside prison.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child stipulates that as long as it is in their best interest, a child separated from one or both parents has the right to maintain personal relations and direct contact with their parent(s) on a regular basis.

Food time at the daycare centre. (Credit: Petride Mudoola)

Bonding time

Within its 21 women detention facilities countrywide, Uganda Prisons currently accommodates 2,468 women and 263 children detained alongside their mothers. With 31 children, Luzira Women's Prison has the biggest number.

Every Sunday, the children are taken to the Women's Prison to visit their incarcerated mothers and are taken back to the daycare centre later the same day.

It is during these reunions that inmates get an opportunity to bond with their children, says Baine.

Angella Akwia, the in-charge of the Family of Africa project, feels that children should not be left to languish because of crimes committed by their mothers, yet often, detention of a single mother leaves her children helpless.

"For many of them (detained women), the events leading to imprisonment rip apart their marriages. As a result, they are abandoned by their husbands yet after detention, newly-released mothers usually have no source of livelihood," she says.

"As a result, some parents would stealthily walk out of prison on release, leaving their kids behind. At one point, they had to look after three children to the extent that the home compelled mothers to a seek court order seeking legal guardianship of their kids before they are taken up for adoption."

'Surviving on goodwill'

Easter Nassimbwa, a child rights advocate, says prison conditions are very poor, with shortage of food and inadequate hygiene as her concerns.

"Funding for these children is inadequate and care for these kids is even not embedded in the Government budget. It is the goodwill of the civil society, well-wishers and innovativeness of the prisons officers."

Presently, the process by which children end up living in prison with their mothers depends on whether or not the mother is arrested along with her young child.

"The process should be formalised and subject to judicial review, with clear criteria developed that take into account the individual characteristics of the child, such as age, sex, level of maturity, the relationship with the mother and the existence of quality alternatives available to the family," Nassimbwa weighs in.

Court should address the question of what happens to children so that they are adequately cared for as the caretaker serves their sentence, bearing in mind the importance of maintaining the integrity of family care and protection of innocent children from avoidable harm.

Nassimbwa says that it seems, in practice, these guidelines are not yet implemented. She says the legal and policy framework for child protection in Uganda is extensive but is not working effectively to care for children with a parent in prison.

The budget allocated to the child protection sector is inadequate (just 0.4% of GDP) yet again lacks skilled staff.

Stigma

Stella Nabunya, the officer in charge of Luzira Women's Prison, highlights stigma and discrimination as effects.

"Of course it's difficult since the child is innocent and has no committal warrants [conviction documents], thus the prison environment does not favour them because the kid is meant to be freely playing with the other children but not in confinement."

"Children with a parent in prison face stigma and discrimination, which is important to address to ensure that child rights organisations raise awareness of these innocent victims and that they need support to deal with that very difficult situation," Nabunya adds.

Sentencing guidelines are key, she says, adding that there is much more to be done to ensure children's rights are respected, protected and fulfilled.

It is through advocacy that issues concerning prisoners' children will become more widely addressed so that the children are visible on the agenda of law and policy-makers.