Why mishandled resettlement could plunge northern Uganda back to war

Like in many countries which have gone through conflict, taking care of such a group is crucial to help them not only recover from trauma, but also help them rebuild their lives, a good distraction from harbouring insurgent thoughts.

With Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) chased out of Uganda and Dominic Ongwen, one of his top honchos, being prosecuted at The Hague over war crimes, peace is back. Northern Uganda is thriving. And poverty there, according to statistics from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), dropped for the first time in over two decades this year, as a result. However, behind that facade of calm is a forgotten problem — the unresolved resettling of ex-child fighters — that could cause problems for peace, writes John Masaba

In 2004, the Government took a sh30b ($8.2m) loan from the World Bank (WB) to reintegrate and skill ex-child fighters. It was obtained under Multi-Country Demobilisation and Reintegration programme to help rebuild the lives of returnee soldiers. However, Saturday Vision has learnt that only 5,335 out of 27,000 abductee fighters benefited from the programme!

When the post-war rehabilitation focuses on securing the return of weapons, rather than establishing holistic disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration of former fighters, the hope for lasting peace pales. Many former fighters have lost their school-going years fighting in the bush. Now, without a means of survival and facing stigma, they are left out of development and are vulnerable to manipulation by insurgents. Isn't Uganda toeing a dangerous path?

Joseph Kony

Joseph Kony

Francis' story

Beads of sweat covered Francis' face, in the afternoon sun. But even with the heat, he continued with a sledge hammer to push his luck at splitting a giant rock.

Each swing of the hammer, however, returned the same results. A little frustrating white dust and no stone chippings for the engineer to work with. By the time he decided the effort was not bearing fruit, his pale orange T-shirt was so wet that it needed wringing out.

Everyday, from dawn to dusk, backbreaking tasks are Francis' routine. Earning him sh3,000 per day, he told Saturday Vision that it is hardly enough for the day's meal and the regular purchases of medicines for his ailing mother.

"When I was young, my dream was to become a lawyer," he said.

But that went up in flames when he was aged just eight in 1989.

"Five men in army uniform surrounded our home and started shooting," he recalls.

It was the dreaded LRA rebels. The shooting sent panic in the area and everybody scampered into the bushes for dear life. He remembers cowering behind their house. He would later feel the rough hands of somebody grabbing him — a tall, dark man spotting dreadlock hair.

"Pe obitwero kwo ma i lum," the man's colleague shouted. In Acholi, it means "He will not be of use to us" — perhaps owing to the little boy's diminutive and fragile frame.

Francis thought that would make him survive, but the man was overruled by colleagues and his fate was sealed.

"They decided to carry me," he remembers.

They would end up in South Sudan at Jabuleni near Juba, where many abducted children from northern Uganda were brainwashed and then given military training. The children would then be used to raid villages, loot and take more boys and girls hostage to fight and satisfy rebel commanders' sexual appetites.

According to documents seen by Saturday Vision, Francis was abducted at Labongo in Kitgum district on February 6, 1989. He was rescued in August 2003, in a clash with Uganda People's Defence Force (UPDF) at Amida Okidi, 20km north of Kitgum town. Records from Kitgum Hospital orthopaedic department show Francis suffered a gunshot in the left leg.

Home at last from captivity, life was supposed to get better for Francis, but that has not been the case.

"Sometimes we sleep on empty stomachs," said the former child fighter.

And he is not alone in that predicament.

Fred's woes

On his clean shaven head, a wide scar runs across Fred's forehead and he walks with a limp.

"I was hit by a bomb. It was a UPDF explosive," he said.

Fred was abducted from Pajule Vocational Institute in Pader district by the LRA on October 10, 2001. It was a big catch for the rebels who wanted more educated personnel to help in the more technical areas, such as reading maps.

"I was pursuing a bricklaying and concrete practice course," he said, adding: "In the bush, I was given the rank of colonel straight away."

He would later command a group of about 1,000 fighters to pillage villages and flee to South Sudan or DR Congo. In total, he confesses, he may have abducted up to 800 children, mostly from Kitgum district.

Fred fled the LRA command in 2004, after Parliament passed the Amnesty Act 2000 that allowed former fighters to surrender and receive immunity from prosecution.

Now living quietly in Kitgum town, Fred is grateful to the Government forgiveness.

"I go about my life without fear that I will be arrested," he said.

But there's a new monster in the room — how he can put food on the table for his family amidst a lack of education or opportunities due to rising stigma against former LRA fighters, for the havoc meted on their communities.

"It's now a dry season," he said. "After leaving the bush, I have been trying my hand at farming, with little success."

Government intervention

When the Government took the $8.2m (about sh30b) loan from the WB in 2004, it was so that people like Francis and Fred get a smoother reintegration into their communities. Like in many countries which have gone through conflict, taking care of such a group is crucial to help them not only recover from trauma, but also help them rebuild their lives, a good distraction from harbouring insurgent thoughts.

However, Saturday Vision has learnt that just 5,335 out of 27,000 abductee fighters — mainly former LRA fighters had benefited from the Multi-Country Demobilisation and Reintegration programme (MDRP).

"Nobody cares for them. I think they are still seeing them as rebels. They have become invisible children," said retired Bishop Macleod Baker Ochola of Acholi Religious Leaders' Peace Initiative (ARLPI).

ARLPI spearheaded peace talks between the Government and LRA rebels, who waged nearly a two-decade insurgency in northern Uganda.

"When MDRP came up, everyone was expectant. Unfortunately, they (returnees) are worse off now than the time they came from the bush," Ochola, who, in protest two years ago, carried some of the returnees to Parliament to raise awareness of the problem, said.

"Many were just dumped in the communities and some are having mental problems. The problem is our perspective. Do we see these children as victims of circumstance or as rebels? These children were taken by force and forced into war. If you are a victim, you need rehabilitation. But they have not been rehabilitated," Ochola said.

Waning aid

Freda was a pupil of Kitgum Public Primary School when she was abducted aged 11 in 2000. She spent four-and-a-half years in captivity, returning in 2005, pregnant with a commander's child.

She has no ill feelings towards the child and is determined to stretch her every sinew to guarantee him a good future.

"My future was messed up, but who knows? My son could become the president (of Uganda)" she said.

But things are hard for the 29-year-old. After chasing for her resettlement package in vain, some weight seemed to have been taken off her shoulders when Kitgum Concerned Women's Association (KICWA), a local charity, offered to sponsor her son in school.

Established in the 1990s at the height of the conflict, KICWA was created as a reception centre to offer psychosocial support, and vocational skills training to returnees.

Last year, however, KICWA told Freda they would not be supporting her child's education anymore. The charity had run out of cash.

"I have left everything to God," Freda said.

With the war over, the number of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) operating in northern Uganda has dropped rapidly. According to records from the Uganda NGO Forum, there were over 500 NGOs operating in the region, but now, only 85 are left.

"When war is over people assume all the problems are over," Alex Ojok, an official at KICWA said. He disclosed that they have abandoned activities that have been benefiting over 200 former abductees.

Tainted deal

Injured in the left leg during his rescue from captivity in 2003, Francis was immobilised for six months. However, after he recovered and went to the Amnesty Commission office in Kitgum to claim his package, he was greeted with shock. "They said I had already picked my share!"

He thought the Kitgum resident district commissioner's (RDC) office through which his initial paper work had been processed might help. Indeed, the RDC, Capt. Santo Lapolo, promised the matter would be investigated. But subsequent visits to the RDC's office yielded nothing, until he gave up.

"When you are a returnee, you do not want many people to know about you. It can work against you. So, many of us prefer to die quietly," he said.

"I know about some people who have never been abducted, but they got the package," he said.

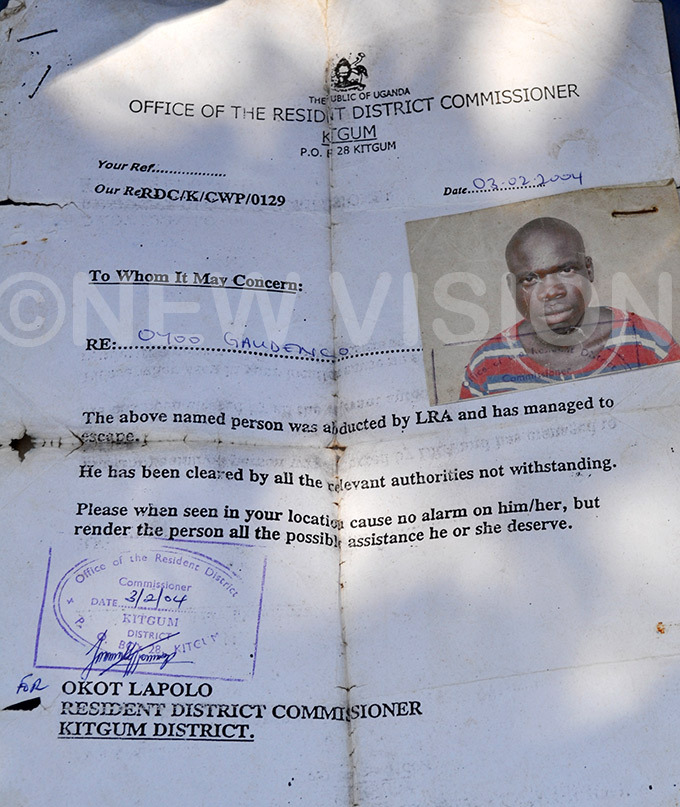

Ayo Gaudensios' certificate from the then RDC of Kitgum Okot Lapolo

Ayo Gaudensios' certificate from the then RDC of Kitgum Okot Lapolo

That sentiment was reechoed by other LRA returnees Saturday Vision spoke to in Pader, Gulu and Kitgum districts.

Saturday Vision sought audience with Lapolo (now RDC Gulu) over the matter in vain.

"Call me later," he said when contacted.

Subsequent calls went unanswered. A visit to Kitgum Amnesty Commission also bore no fruit as the office has been abandoned and is now under lock and key.

Now as a cloud of unaccountability hovers over the MDRP programme, the situation of the ex-fighter is not about to improve.

"I have met a few of them (former abductees), but when you look at them, you realise how lucky you are because they are in very bad shape," Francis, a porter in Kitgum town, said.

On the other hand, Fred says he was denied a chance to access the Youth Livelihood Programme last year on the basis of his status.

"They said they could not trust if we could return the money because, any time, we can return to the bush," he said.

He has also tried to join the army, but could not pass the fitness test as he is deemed disabled, having been injured in the leg.

In the meantime, he has been scouring Kitgum for casual jobs to survive, but the odds are heavily stacked against him.

"If some people they realise you are a returnee, they deny you the opportunity to work," Fred said.

But a solution needs to be found.

"Some who could have hidden a gun could go back for them. That is how (Onen) Kamudulu got into trouble," Francis said of the former LRA operations commander, who got amnesty in 2004, but would later be arrested in 2009 after he was implicated in a robbery. He is currently in prison in Gulu.

"When somebody has given up on life, anything is possible," Dr Paul Nyende, a lecturer of psychology at Makerere University, said.

"Lack of opportunities and stigma for many returnees are a dangerous combination. When you cannot find acceptance from family, the gang (can easily) become(s) your new home," he said.

New rebel group

The report about MDRP programme comes against a backdrop of reports that former rebel fighters in West Nile are forming a new rebel group. Lt Col. Ernest Obitre Gama, the chairperson of the Amnesty Commission for north western region, told Saturday Vision: "I rushed there and met the district internal security officer and the RDC. They all confirmed the report (of new rebels).

Our intelligence is that they are joining a rebel group in South Sudan (name of group yet to be established). We are told they are paid $400 (about sh1.4m)." Gama said the group are former fighters of Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF). But UPDF spokesperson Brig. Richard Karemire denied knowledge of the group. He said, however, they are aware of groups of ex-fighters that have not been resettled.

"(But) joining rebellion is not a solution. We do not support any machinery, like activity against an elected government," he said.

He added: "The solution is in engaging relevant authorities to find out what has caused the delays (of releasing the money)."

Amnesty Commission responds

Amnesty Commission's spokesperson, Moses Draku, clarified that 21,000 ex-fighters had been paid, instead of 5,335. He said, however, that the situation was still ‘bad' with reintegration, which ex-fighters badly need. The commission is cash-strapped, he said.

Out of 27,000 ex-fighters, he said only 8,000 have been reintegrated (given vocational skills).

"We are also concerned (about the implications) as you are, but what can you do? I wish we had our own bank," he said.

Reminded about the $8.2m WB loan, Draku said: "I am not sure that is the sum ($8.2m) we got."

He, however, declined to give further details.

In light of mounting numbers of un-resettled ex-fighters, he said: "We asked the Government to allow us mobilise support from foreign partners. Unfortunately, we have not made much success. We (therefore) have to depend on what we receive from the Consolidated Fund."

Juliet Akello, a policy officer at the Uganda Debt Network, which monitors utilisation of government loans, says there is urgent need for the Government to carry out a re-evaluation of all programmes at Amnesty Commission due to its bearing on national security.

"It is important that the Auditor General prevails over establishing its implementation (of programme) to enable a clear analysis of its effectiveness and value for money," Akello said.

She added: "If we are talking about northern Uganda, what could be the situation for programmes for other regions? It could be worse."

Saturday Vision has learnt that there are 27 other former rebel groups that have applied for amnesty.

"Last year, we cleared a group in Kapchorwa called the Uganda Saving Force. This year, I think we shall be working on another in Kiryadongo district," Draku said.

Efforts to get a comment from the WB were futile as e-mailed questions to Sheila Kulubya, WB's spokesperson in Uganda, were unanswered.

Quick glance at MDRP

Each returnee would get cash allowance of sh263,000; a mattress, blanket, basin, and garden materials, like hoes, seeds

Each ex-fighter is entitled to vocational skills training

Entitled to psycho-social support to aid recovery

Amnesty Commission to sensitise public about the Amnesty Act to reduce hostility and stigma towards returnees

Amnesty Commission also received funding from the UN Development Programe, Ireland government, African Union and Danida.

Returnees a time bomb

A report by the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour, a United Nations agency report: Economic Reintegration of Children Formerly Associated with Armed Forces and Armed Groups (2010), says many countries that have previously come out of war make one common blunder — they focus on securing the return of weapons, rather than establishing holistic disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration programmes to comprehensively help fighters return to civilian life.

Yet many are former child soldiers who have lost their golden school-going years fighting in the bush. Without a means of survival and facing stigma, most of them are left vulnerable to the manipulation by insurgents, the report said.

"There is no shortage of countries that enjoy brief interludes of peace before returning to armed conflict. Having recently emerged from a civil war is one of the strongest predictors of future violence," the report revealed.

The report references Sierra Leone and Liberia, which suffered spate after spate of rebellion, until early 2000s. Sierra Leone erupted into a civil war in 1991 and it was not until 2002 that peace returned. By then 50,000 people had lost their lives. Liberia, on the other hand, lost close to 250,000 lives in the 1989-1997 conflict.

Because of a lack of education, the report revealed, many of the ex-fighters were likely to be without skills to make themselves useful in the job market. This tends to perpetuate poverty among the group, leading to helplessness — a fertile motivation for those people to be lured by people with criminal minds, the report said.

"Addressing the underlying causes of recruitment, therefore, means providing and facilitating access to education and, for older children, to attractive training and employment opportunities," the report said.

"They call me Kony and lacilo — a dirty person"

When we met for the noon appointment at his home in Omiya Anyima, about 30km south of Kitgum town, Gaudensio Ayo knew he had to have his emotion in check. It is distasteful in his Acholi culture for a grown man to shed tears before his children. But Ayo could not hold back. It was an awkward moment.

"A poor person in our culture is one with no eyes and limbs, but I am poor, even when I am perfectly able-bodied," he said, wiping teary eyes with the sleeves of his shirt. In 2001, Ayo was seized from his home by rebels in his village, spending three-and-a- half years in captivity.

The suffering was immense. He speaks of one day being forced to carry a 100kg bag of posho and being whipped 150 strokes of the cane after he collapsed under the weight of his load.

In 2004, when he fled from the rebels, he was hopeful of a new life with his family. But he has quickly found himself an outcast, shunned and called names by his extended family members. "They call me Kony. That I killed my own people. They say I am lacilo — a dirty person," he said.

"Now, tell me, where I should go," he said.

He said he has pondered suicide. "But", he added adjusting his little son's shirt collar: "who would take care of him?"

Additional reporting by Wokorach Oboi

RELATED TO THE STORY

Battling the effects of LRA rebel abduction

ICC president asks state parties to provide for the victims of war

Northern Uganda war victims face stigma

Acholi cannot handle the effects of the LRA war, ICC told

Down but not out: LRA haunts Central Africa