Don't blame the gods for Africa's water crisis

City residents across the continent have come to expect water rationing and dry taps as a matter of course. Officials in Nairobi, Kenya have said rationing will continue until 2026 as the dam that waters the city runs dangerously low.

Cape Town's taps will dry up in a few weeks. That a modern metropolis could run out of water may have once seemed a remote possibility, a plot line from a post-apocalyptic fi lm. But it is now almost inevitable that Cape Town, South Africa will turn off water supply to homes due to drought.

This story has grabbed global headlines in the last few months. However, its sheer prominence has obscured the tragic fact that this South African city's water problem is only one chapter of a story playing out across the continent. Rivers and lakes are dying before our very eyes. Lake Chad, once a life-source for communities of the Sahel, is disappearing into the desert and birthing one of the most complex humanitarian disasters in the world.

City residents across the continent have come to expect water rationing and dry taps as a matter of course. Officials in Nairobi, Kenya have said rationing will continue until 2026 as the dam that waters the city runs dangerously low.

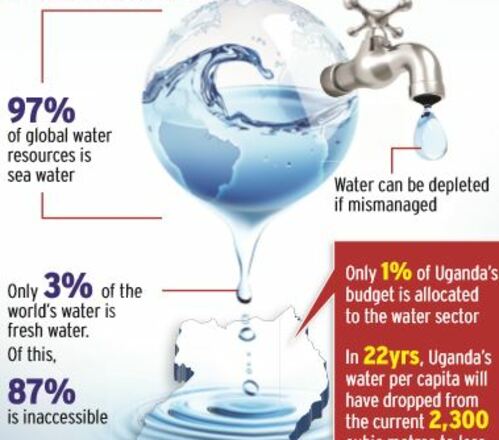

The price of a jerry can of water has doubled in parts of Uganda and in August last year, authorities in Kigali had to slow down new water connections because there simply was not enough water to go around. Malawi in 2015 took the unprecedented action of sending soldiers to protect one of its water towers, as Lilongwe faced acute scarcity.

The water situation has not improved much since then. The World Bank last year warned that Tanzania had crossed the threshold to become a "water stressed" country. The roots of Africa's current thirst are manmade. As temperatures rise with climate change, rainfall can no longer be expected to stick

to patterns that were established millennia ago. Prolonged droughts and strange floods are becoming all too common. At the same time, human demands on nature have risen. UN Population data shows that the continent's population grew from 228.7 million in 1950 to 1.2 billion in 2015. Africa's population has grown more than five-fold, its water resources have not.

The demographic changes on the continent have also had indirect implications on water availability. More people require more homes, more agricultural land. Forests, valuable as water towers and for carbon sequestration, have been sacrificed in the name of development.

Some countries have been hit worse than others. Nigeria's forest cover fell from 18.9% in 1990 to 7.7% in 2015, according to World Bank data. In Uganda the forest cover was reduced from 23.8% to 10.4% during a similar period.

Distribution and allocation policies for the little water that is available leave much to be desired. While Cape Town is going through a historically devastating drought, research has also shown that better public policy implementation could have helped mitigate the current disaster.

Mismanagement of public funds stalled investments in Rwanda's water networks, exacerbating a water shortage last year. Rivers have been turned into a poisonous sludge of human waste and industrial effluent. For millennia, the Nile has been the lifeblood of Egypt but segments of it have become so polluted, that fishermen, whose families have relied on its waters for generations, are repelled.

This sort of scorched earth development is unsustainable beyond one or two generations. In the short term a forest might seem an obstacle

to a new tea farm. In the short term dumping waste into a river may seem an easy way to cut costs for a factory. In the long term, neither the factory nor the tea farm will be worth much without water. The consequences of our negligence are playing out in everyday life in varying degrees of tragedy.

For middle-class city dwellers, water scarcity may simply mean an extra shilling or a franc paid to a private supplier, a negligible rise in the price of the basic commodities. It is those people that have to weigh the cost of a jerrycan of water versus a loaf of bread that are the most vulnerable. It is the rural poor that can no longer feed themselves and

that lose days of work in search of water for their livestock and children that are paying the true cost of negligence. Water scarcity also has bloody consequences.

It is already fueling conflicts in parts of the continent. Droughts ratchet up tensions among pastoral communities, who are more likely to go into battle to protect the water rights of their livestock. In Malawi rural communities have begun to protest piping water from their forests to serve thirsty Blantyre.

At a macro-scale, sabre rattling has sometimes characterized the fraught negotiations over the use of the waters of the Nile. These conflicts among people over water are usually prefaced by confrontations with wildlife.

The Maasai Mara ecosystem is threatened by the drying up of the Mara River, a phenomenon that has been connected to the destruction of a forest complex, hundreds of kilometres away. Already crocodiles and hippos have started dying. Those animals that can migrate are bound to collide violently with pastoralists and farmers also going after the same scarce water resources. Just as Africa's water scarcity seems to be aggressively man-made, so too must the solutions.

Across the continent steps are being taken in the right direction. Kenya has issued a 90-day ban on logging as it seeks to beat back the depletion of its forests.

Rwanda is investing more in its water infrastructure. South Africa is pioneering waste water recycling on the continent and farmers in Niger, on the edge of the Sahel, are rediscovering old tools for preserving water beating back the encroaching desert by nurturing indigenous plans.

Rwanda and Ghana have bucked the trend, increasing forest cover while the rest of the continent has been losing trees. But we are still strolling where we ought to be running. Even as we provide emergency aid to those that are vulnerable, long-term strategies must involve policy changes to adapt to climate change and to protect what is left of water resources.

Investment in infrastructure to reach those who lack access and improvement in existing systems to reduce water wastage will be crucial. Collaboration will be key at every step of the way. Water is not a resource that respects man-made boundaries and experience has shown that a single action at any point of the water cycle has the profound implications far and wide.

Sub-national and national authorities will have to listen to each other and align their policies and actions if they hope to sustainably address water scarcity.

Written by Kaddu Sebunya

The writer is the president of the African Wildlife Foundation ksebunya@awf.org