Mac Maharaj on Mandela and South Africa

When we look back on the life and times of Mandela several attributes stand out. He was a man of action.

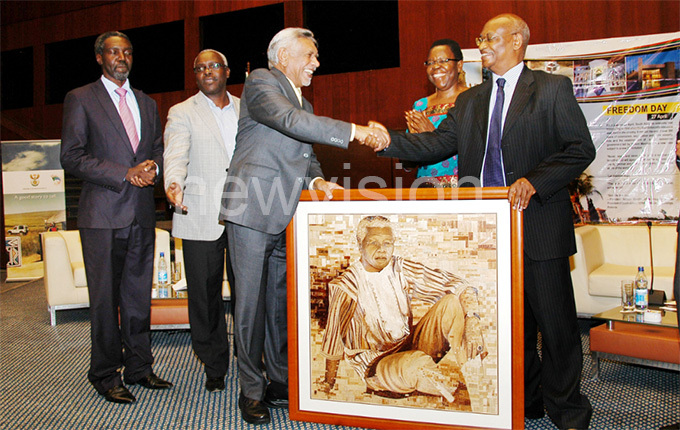

A South African freedom fighter, Mac Maharaj (left) speaks during the Nelson Mandela memorial lecture at Kampala Serena Hotel on July 15 2016. Right is the former minister of Agriculture, Victoria Ssekitoreko. PHOTO: Ronnie Kijjambu

By Mac Maharaj

Nelson Rohlihlala Mandela, endearingly known among us as Madiba, once wrote that "Men and women, all over the world, right down the centuries, come and go. Some leave nothing behind, not even their names. It would seem that they never existed at all."

On 18 July it shall be his 98th birthday. On the 5th December this year it will be three years since this great son of Africa left us. Sufficient time has elapsed to enable us to pronounce without fear of dissent, that Madiba's footprint is deeply carved on the rock face of the history of our continent and burnished into the minds of peace loving people around the world.

It is a footprint that is intimately connected to the theme of today's conversation: Take Action, Inspire Change.

When we look back on the life and times of Mandela several attributes stand out. He was a man of action.

However, action for social change, needs to be preceded by careful thought and planning, by tailoring action to achieve desired goals. Without this, action becomes irresponsible, if not anarchic.

Madiba was a man of action with a vision.

He was driven by a firm belief and commitment to Africa's freedom, to empowering the people to shape their own destiny, and to the world-wide struggle to eradicate poverty.

The more he thought about it, the more he realized that freedom is indivisible. In his prison desk calendar dated June 2, 1979 he recorded that "the purpose of freedom is to create it for others."

He saw poverty as one the greatest affronts to dignity. Poverty, he told a crowd of more than 22,000 people gathered at Trafalgar Square, London in 2005, "like slavery and apartheid, … is not natural. It is man-made and it can be overcome and eradicated by the actions of human beings." He held fast to the view that "Overcoming poverty is not a gesture of charity. It is an act of justice. It is the protection of a fundamental human right, the right to dignity and a decent life."

With an outlook anchored in the pursuit of freedom and the eradication of poverty, Madiba booked his place on the freedom train.

Making a reservation on the train is the easy part. The freedom train is neither a free ride nor a joy ride. It takes blood, sweat and tears to stay on it.

It is on the freedom train that Madiba tells us that he "learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it. The brave man is not he who does not feel afraid, but he who conquers that fear."

In the political report of the National Executive Committee that he presented to the 49th ANC National Conference held in December 1994, we were reminded that on the freedom train the "blind pursuit of cheap popularity has nothing to do with revolution."

Oh, how often, in prison and in retirement we have chuckled together about shared experiences. I recall one small - some may say insignificant - incident that took place in the Robben Island prison yard during the early part of 1965.

We were seated on cold, hard, concrete blocks, pounding slabs of stone into pebbles with four-pound hammers, when a common law prisoner, Bogart, was physically assaulted by a warder. Bogart was a hardened serial criminal with a scarred face and a fearsome, cold, murderous look in his eyes. He and a handful of common law prisoners were placed among our group by the authorities with the express purpose of terrorizing us.

It seemed a twist of fate that here was Bogart being assaulted by his keepers, his manipulators. Mandela instantly got up and remonstrated with the warder and demanded to see the commanding officer so that he could pursue his complaint with a view to ensuring that such brutality was not repeated, neither on Bogart nor on any other prisoner.

Some among us murmured that Madiba should not pursue the matter on behalf of Bogart. Bogart was a brutal serial criminal guilty of several offences involving violence; he was put in our section to torment us; he could not be trusted.

But Mandela was unrelenting. The upshot was that later that afternoon Mandela was taken to the office where the commanding officer heard him out.

Then Bogart was brought into the office and asked, in the presence of Mandela, whether he had been assaulted by the warder as alleged by Mandela. Bogart flatly denied being beaten.

The officer cautioned Mandela that in terms of the prison rules a prisoner was only allowed to raise complaints he personally faced and was not allowed to speak for others. Furthermore, he warned Mandela that raising false complaints was a punishable offence carrying a penalty of up to six lashes.

We teased Mandela about the incident but he was unrepentant.

Was his action a simple act of standing up against injustice, of empathy for the underdog? Indeed, Mandela argued that the freedom struggle involved "fighting injustice wherever we found it, no matter how large, or how small."

But Mandela's action made us aware of an additional dimension: as he put it, "we fought injustice to preserve our humanity." In the privacy of my conscience and through such small incidents, I was chastened and my horizons widened.

The journey on the freedom train is one where hardship, suffering and solidarity drill into us the realization that "a revolution is not just a question of pulling a trigger; its purpose is to create a fair just society."

And so, on board the freedom train, we are moulded to contain vanities of the self in an act of selflessness that teaches us that "No single person can liberate a country. You can only liberate a country if you act as a collective."

These are not attributes that we are born with. Nor are they learned in a classroom. No matter how much they may be drummed into us in the lecture room, it is in struggle, it is on the freedom train, in the heat of battles, that one absorbs them in ways that they come determine one's behavior and the choices one makes.

Change happens when ideas are combined with action. William James puts it pithily when he tells us that "You can't leave a footprint that lasts if you're always walking on tiptoe."

Mandela was never one to "walk on tiptoe." Having supported the proposal for the launch a mass defiance campaign, he accepted the task of serving as the volunteering-in-chief, together with Yusuf Cachalia. He did so notwithstanding the fact that he was about to complete the requirements for being admitted as an attorney, which promised an escape from penury. In fact, arising out of the Defiance Campaign, he, together with several others, was brought before the court and convicted. Attempts were then made to oppose his admission to the roll of attorneys on the basis of this conviction.

At almost all critical moments in the struggle Mandela never hesitated to put aside his personal interests in favour of the interests of the struggle.

He was at the heart of every militant campaign launched by the ANC and its allies and no amount of harassment, threats of imprisonment, court trials and restrictions deterred him from taking up whatever duty the movement called him to perform.

At the very moment that the four-year old treason trial, in which he was an accused, was coming to an end, he accepted the task of serving as secretary of the National Action Council which was entrusted with organizing the national stay away in 1961. It was a task that led him to lead the life of an outlaw, forever sought for by the security police and always on the run organizing, planning and implementing moves that were aimed at keeping the freedom train moving.

Before I went to prison I had read about the history of many struggles around the world and thought I had absorbed their lessons. One of these was that a good cadre stood on guard duty when people celebrated a victory in the struggle because of the danger that the enemy may choose that moment to launch an attack, and that a good cadre moved into the frontline to shield the people from the blows of the enemy. I wanted to be a good cadre.

A small incident in prison made me realize that it was easy to claim revolutionary principles; it was another matter to live them out in practice.

I was at the time serving as the chair of the prisoners' committee - it was a rotating position. Our task was to represent and take up issues relating to our conditions and treatment meted out to us.

We had just returned from working at the lime quarry. A small incident - a fracas between us prisoners and a group of warders, who seemed about the unleash their batons on us - exposed my inability to diffuse the situation.

By this time some prisoners had rushed off to the showers, while Walter Sisulu and another had rushed off to the far end to settle a grudge re-play match on a make-shift draughts board.

I raced over to Sisulu and sought his help. He said he would come once his game of draughts was over! Blinded by my helplessness, I thought to myself: Heaven help us when my leader, Walter Sisulu, believes that completing a draughts game is more important than saving his comrades from a beating!

I ran back to the scene of the fracas. As the warders advanced I took refuge in the middle of the prisoners. I had become more concerned to save myself from the blows of a baton than helping my comrades.

Then suddenly the atmosphere changed. When I looked up there was Sisulu right in front of the prisoners and standing face-to-face with the warders and trying to diffuse the situation. I had left Sisulu at his cursed draughts game. How he had come over and unnoticeably moved to the front to face the warders is something I never quite worked out. But there he was right in the frontline of the danger that faced us, while I, the chair of the prisoners' committee had taken shelter in the middle of my fellow prisoners. So ended my dreams of being a good cadre.

I hope therefore you will appreciate why a precept by which Mandela lived carries so much meaning for me. Mandela in his own words tells us that "You take the front line when there is danger. Then people will appreciate your leadership."

Committing oneself to disciplined collective action is not always a comfortable zone, especially for those in leadership positions. I can think of at least three occasions when Madiba had either spoken out or taken positions for which the National Executive of the ANC rebuked and censored him.

It happened in 1953 when at a public meeting he suggested that the time had come to abandon the tactic of non-violence. It happened again when he took the same stance when the 1961 stay-away was suppressed by the state. In each instance he acknowledged his mistakes and adhered to the discipline of the collective.

I recall another instance with some glee. We were heading for the democratic elections of 1994 in which all South Africans, irrespective of race, colour or gender would for the first time exercise the vote.

Madiba appreciated that our youth and even children, through force of circumstance, found themselves during the seventies and the eighties in the frontline of the struggle against the might of the racist state. He proposed that we should extend the vote to fourteen year olds.

Some of us in the NEC were taken aback and challenged him. He stood his ground, finding all sorts of reasons why it was fine to have fourteen year olds exercise the vote. He dug up a list of countries where teenagers had the vote. Some of us - yes, in whispered tones - mocked him, by saying this meant Madiba wanted a fourteen-year old to be president of the country! In the end the NEC shot down his proposal.

In the course of reminiscing we teased him about this and asked whether he now acknowledged the error of his views. No, retorted, it was not our arguments that had prevailed. In the middle of the debate there had appeared a cartoon in a newspaper depicting Madiba ensconced in a baby pram, dressed in a napkin and sucking at the teat of a milk bottle, while advocating the vote for fourteen-year olds. That he said, is what changed his mind, not our arguments!

Being part of a collective, especially when serving in its leadership, calls on one to abide by the judgment of one's comrades even when one is convinced that their view is not the right one. In fact, it is even more demanding than that.

It is not unusual in the struggle for freedom that decisions we take produce unintended consequences. Imagine yourself in the leadership collective that had acted on a decision you were unhappy about. Now you are faced with consequences such that instead of advancing the movement, they carry the potential to set us back. What do you do in such a disasterous situation?

Do you exonerate yourself by indicating that you had opposed the decision? Do you try to focus attention on who to blame for the impasse that has arisen?

That critical juncture when your movement faces a setback is not the time to play the blame game. That is an exercise you will conduct at a later time. Right now the critical issue is to turn the setback into an opportunity. It is the moment to take stock of the situation created by the unintended consequences, accept those consequences as a reality, and map out a way ahead for the collective and its leadership. It is a time to gather your forces, regroup, define a path that turns the situation that has arisen into an opportunity to adopt and implement actions that keep the struggle alive.

It is a time not for recrimination - recrimination succumbs to and magnifies the fears inherent in the situation. It is time for cool heads, calm deliberation and careful choices. And in making those choices Madiba tells us to ensure that "your choices reflect your hopes and not your fears".

To put all this in words and on paper makes it sound easy, too easy. Some among you may be thinking that I am talking nonsense. In reality carrying this out in practice is hugely demanding.

Mandela and his colleagues faced such a moment during the Rivonia trial in 1963 when they faced the real prospect of finding themselves in death row. The prosecution case relied on a document found during the police raid on the Rivonia farm, entitled "Operation Mayibuye."

It outlined all kinds of fanciful plans, including the landing of combatants by sea and air, and a guerilla force of 7000 throughout the country. It was a plan out of touch with the real world in which we lived. It had been conceptualized and drafted while Mandela was already in prison.

While Mandela could speak authoritatively and with direct and intimate knowledge about events during the period of the formation of uMkhonto as well as the first acts of sabotage carried out in December 1961, he had no first-hand knowledge of events after 10 January 1962 when he was sent by the ANC on a mission abroad to solicit financial, military and other support from the African states.

He returned from this African trip on 24 July and was arrested on 5 August 1962. In so far as the trial was concerned Mandela therefore had no first-hand knowledge of events during the period when most of the acts of sabotage were carried out by uMkhonto. Nor was he familiar with the circumstances when Operation Mayibuye was developed.

Who then should be the key defence witness in the trial? Clearly there were others among the accused who could account for the founding of of MK and events surrounding it up to the time of the arrest on 11 July 1963. It was a touch and go situation as to whether some of the accused would succeed in avoiding the death sentence.

Let me allow one of the accused in the Rivonia trial to take up the story at this point. Rusty Bernstein in his memoirs titled "Memory against Forgetting" asks whether under these circumstances would it not have been more sensible for Mandela to leave the responsibility to another of his co-accused to explain things that he could not have influenced even if he wanted to? Bernstein recalls:

"Nelson would have none of it. I am not surprised. As long as I have known him he has acted on the principle that leaders have no special privileges, but have special obligations and duties greater than those of others. He rejects any special protection and insists on his responsibilities as titular head of MK. He will explain the ANC and its role in respect of MK, and defend them both in court. He will take on the full fury of the state attack - it is the obligation that falls on a leader. He puts his arguments forcefully, and everyone - lawyers and accused - concede he is right."

The accused decided that they would not deny responsibility and the defence strategy was based on persuading the court that Operation Mayibuye had been discussed but never adopted, and to use the trial as a political forum to explain and define the nature of their struggle.

A key element in implementing this strategy was now to have the defence open its case with Mandela, the first witness for the defence, addressing the court from the dock and not the witness box.

Mandela prepared a final draft and showed it to his co-accused and defence team. His draft outlined the nature of the struggle and the commitment of the accused to it. He provided the court with a history of the ANC and its attachment to non-violence and explained why uMkhonto was established as a separate organisation. He referred to the four stages of sabotage, guerilla warfare, terrorism and open revolution and explained that MK had decided to test the stage of sabotage fully before taking any decision to escalate to the next stage and that he had undergone military training outside the country so that in the event of resorting to guerilla warfare he could fight alongside his people. He carefully outlined why the struggle for freedom was necessary and that it was a truly national struggle.

He concluded his draft with a statement that "I have fought against white domination and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for, and to see realized. It is an ideal for which I am prepared to die."

Let us return to Rusty Bernstein who in his memoirs explains that "The prospect of a possible death sentence is never far from any of our minds. It requires a special courage to confront it starkly as Mandela does, and to throw down a challenge to the court to impose that penalty if it dares. We are uneasy about it. His blanket admission of responsibility for MK and sabotage is bold enough without it. Mandela listens to the arguments with his customary gravity. He is not posturing. He knows as well as any of us that he will be balancing on a knife-edge between life and death. But he is the leader, and in his mind the responsibility must be his. The coda stays as drafted."

In fact, one change is made to the draft. A small modification in the formulation of the last sentence is proposed by the defence lawyer, George Bizos, to the last sentence in the draft which read: "It is an ideal for which I am prepared to die." Bizos' proposal is intended to soften the direct challenge to the court to impose the death penalty if it dares. It is amended to read "But, if need be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die."

I recount this for several reasons. While some of the accused differed sharply among themselves as to whether Operation Mayibuye had been adopted, they did not allow their differences to descend into recrimination and a blame game, In the face of what was one of the severest setbacks suffered by the struggle Mandela's address, in its content and tone, would remain a beacon inspiring and guiding the struggle even if they were to pay for their actions with their lives. Come what may, that is what they intended it to be.

And the four of them who were members of the National Executive Committee of the ANC, namely Mandela, Sisulu, Mbeki and Mhlaba, had agreed among themselves before the day of their sentencing that they would not appeal if the court imposed the death sentence on them.

It was an approach the accused stood by and it was something that coincided with Mandela's personal credo, which was that "I am not what happened to me; I am what I choose to become." It epitomized the ultimate test of a leader as one who is prepared to take responsibility for the choices he has been party to even when faced with severe unintended consequences.

Indeed, that speech from the dock became the touch stone for all who within the ranks of the ANC and its allies and wider circles kept the freedom train moving, be it from within the country in the face of massive repression, in exile or in prison. It became a source of inspiration which during the darkest days of the struggle kept the flame of freedom alive.

In January to April 1976 when Madiba wrote the first draft of his autobiography, uMkhonto military campaigns, mounted in alliance with ZIPRA, the armed wing of ZAPU, and aimed at hacking a path through the then Rhodesia into South Africa, was long over. SWAPO in Namibia had more than seventy of its combatants, including its leader Toivo Ja Toivo, serving long prison terms in South African prisons. The lull in mass activity in South Africa that set in after the April 1961 strike symbolised the rampant power of apartheid state repression.

The series of strikes that began on the docks of Durban and spread through the Durban-Pinetown industrial complex in 1973 was the only manifestation of mass action.

The Soweto Uprising of June 1976 was yet to come and no commentator, analyst or activist in South Africa anticipated it at the time Mandela wrote "The Long Walk to Freedom".

By this time Madiba who was serving a sentence of life plus 5 years had been in prison for fourteen years. Not only had the movement suffered setbacks and was struggling from exile to rekindle the struggle within South Africa.

At a personal level Mandela had during those years endured the psychological torture and torment of losing his mother, Nosekeni Mandela, and eldest son, Thembi. He was living through the harassment and torture that his wife, Winnie Nomzamo, was undergoing, he was unable to comfort his eldest daughter, Maki, and his only surving son, Magkatho, and he was helplessly witnessing the agonies his daugthers, Zenani and Zindzi, whom he had left when they were toddlers when to disappeared into the underground.

In his autobiography you can feel the searing pain of what the movement and his family were undergoing. You can sense the flashes of anger and anguish that such moments generated in him, but you will find not even a whiff of a sense of victimhood in his writings and in his conduct. There was no space in him to feel sorry for himself.

He lived his life on the basis of some simple propositions. Life and the struggle was about making choices. The choices you make should reflect your hopes, not your fears.

Choices have consequences which are usually not what one intended. That is when a leader rises to the occasion by looking forwards, not backwards, by taking responsibility for the situation that has arisen and turning the unwanted consequences are turned into opportunities, which in turn require choices to be made.

Within endless cycle of choices, consequences, opportunities, and choice lay the core of taking responsibility for the consequences and finding a way forward.

Madiba shared the wisdom born of the hardships that are the inevitable accompaniment of struggle when he urged that "What counts in life is not the mere fact that we have lived. It is what difference we have made to the lives of others."

Such was journey on which the freedom train took Madiba. There is always room on it.

Maharaj was a political activist who worked in a clandestine manner on anti-apartheid activities with Nelson Mandela. In July 1964, Maharaj was arrested in Johannesburg, charged and convicted with four others on charges of sabotage in the little Rivonia trial, and was imprisoned on Robben Island with Mandela. In prison he secretly transcribed Mandela's memoir Long Walk to Freedom and smuggled it out of the prison in 1976.