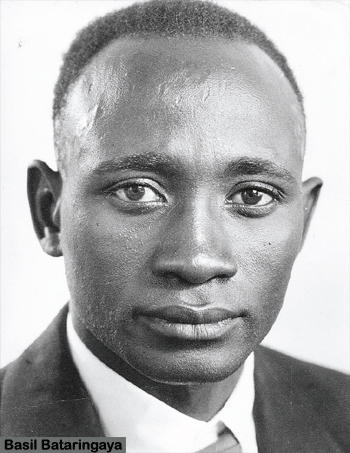

Basil Bataringaya, the father of opposition cross-overs

Today, JOSEPH SSEMUTOOKE revisits the past and brings the role contributed by Basil Bataringaya, Uganda's first leader of Opposition in Parliament to cross to the ruling party

To those familiar with his name (and they aren’t really many), Basil Bataringaya was simply the home affairs minister during the Obote I regime who was brutally murdered by Idi Amin’s henchmen in the fi rst years of the regime. Many, therefore, know him just as one of the earliest and most high profi le victims of the dictator’s bloody regime.

DP strongman, first leader of the Opposition in Parliament

Bataringaya joined politics as a student, when he was elected Makerere University College Guild president for 1955 to 1956. He arrived on the national political scene following the 1960 LEGICO elections, when he was elected one of the Members of Parliament for Ankole district on the Democratic Party (DP) ticket. He quickly won himself popularity in DP and went on to be appointed minister for local government in Uganda’s fi rst native government — the Ben Kiwanuka-led pre-independence government, which shared power with the outgoing colonialists between 1961 and 1962. He is described in the book Parliamentary Democracy in Uganda: The Experiment That Failed, as an intelligent, articulate, supple, conciliating and infi nitely persuasive character, whose gift for political manoeuvre made him a natural choice for important posts. The same book also talks of him as a quick-witted fellow with a grand fi nesse at debating. On the eve of independence in 1962, DP lost the national elections to the Uganda People’s Congress and Kabaka Yekka parties (the UPC-KY) alliance. With a majority in Parliament, the UPC-KY alliance went on to form the ruling government, while DP became the House’s Opposition side. DP president general Benedicto Kiwanuka was among the party’s many Baganda leaders, who had failed to win parliamentary seats in the election; so Bataringaya, who was DP’s secretary general and thereby the party’s Number Two, became the country’s fi rst post-independence Leader of Opposition in Parliament.

The same book also talks of him as a quick-witted fellow with a grand fi nesse at debating. On the eve of independence in 1962, DP lost the national elections to the Uganda People’s Congress and Kabaka Yekka parties (the UPC-KY) alliance. With a majority in Parliament, the UPC-KY alliance went on to form the ruling government, while DP became the House’s Opposition side. DP president general Benedicto Kiwanuka was among the party’s many Baganda leaders, who had failed to win parliamentary seats in the election; so Bataringaya, who was DP’s secretary general and thereby the party’s Number Two, became the country’s fi rst post-independence Leader of Opposition in Parliament.

Conflict with Kiwanuka

Bataringaya’s being the leader of opposition in a Parliament where Kiwanuka was absent soon created a power struggle within the DP hierarchy. Reportedly, Bataringaya saw his president general as a man driven by arrogance to behave intransigently toward Mengo, and therefore, an obstacle to DP’s goals of attaining power since Mengo’s support was needed to get there.

Soon Bataringaya had won several DP members onto his side, especially the DP members in Parliament, and they began to openly resent Kiwanuka’s leadership. Shortly after, the top-ruling committee of the party was calling for Kiwanuka to step down and surrender the party leadership to Bataringaya. However, Kiwanuka clung onto the party leadership and, consequently, Bataringaya organised a delegates’ conference where he challenged Kiwanuka for the party leadership. Ironically Kiwanuka defeated Bataringaya in the elections and retained the party leadership, and the rift between the two DP leaders widened.

The crossover

In 1964, following an endless tugof-war with Kiwanuka for the party’s leadership, Bataringaya wrote a new chapter in the country’s political history when he, together with six other DP MPs, crossed over from the opposition side of Parliament to Obote’s ruling cabinet bench, becoming the fi rst opposition bigwig in Ugandan politics to cross to the ruling bench, a feat that subsequently became common in Ugandan politics over the next decades. Obote appointed him home affairs minister. While some say Bataringaya’s crossing was driven by his nationalism and desire to serve his country in whatever camp he could be given an opportunity to do so, others say as a moderate, Bataringaya had wanted to have DP (if it couldn’t get power) to at least combine with UPC to jointly work for the progress of the country. That when Kiwanuka proved a stumbling block to this aspiration, Bataringaya decided to serve his country directly under UPC. However, others say he crossed only for his personal gains after Obote promised to reward him.

These say when Obote realised the opposition party was politically stronger than his ruling UPC, he decided to weaken it by either assimilation or extraction of its strongest pillars. That Bataringaya’s attempt to become party president was thus only an attempt to take full possession of DP and deliver it to UPC, and when he failed he opted to cross with the few he could convince to go with him. Those who stayed in DP under Kiwanuka included Boniface Byanyima, Martin Okello, Gasper Oda, Payarhabai Patel and Alex Latim, who replaced Bataringaya as leader of opposition in parliament.

Obote’s pillar

Whichever way his cross over may be seen, one undebatable fact is that Bataringaya became a key pillar of the Obote I government. Obote appointed him to the infl uential ministry of home affairs and came to rely on him so much that he became one of his fi ve-man inner circle that ran the country.

Unlike the other leaders whom Obote drew close and placed in powerful positions primarily because of ethnic reasons or because they supported him through the years, Bataringaya is said to have attained the President’s favour and trust mainly because he was an effective, intelligent and forward-looking man that Obote wholly respected. It is said whenever there was an issue to be addressed at home, Bataringaya was one of the men Obote sat with to map a way forward, and that whenever something was not right in the political set-up, Bataringaya was one of the few people Obote charged with the task of putting it right.

Blamed for the regime’s blunders

Bataringaya’s legacy in the fi rst UPC government is, however, also littered with blame for many of the blunders the regime committed. Some argue this is because as the home affairs minister, he was held responsible for everything the government did — much of what he didn’t commit. But his opponents say Bataringaya played a direct role in the blunders.

Many Baganda blamed him together with Milton Obote for the hostilities of the 1966 Crisis. Here he was pointed out as the implementer (in his capacity as home affairs minister) of Obote’s harsh measures against Buganda, such as the arbitrary arrests and killings of several of the Kabaka loyalists and associates following the 1966 crisis, as well as for initiating and maintaining the state of emergency that was declared in Buganda at the time. Those who oppose this view say Amin used his army to commit the atrocities.

Among Amin’s first victims

Bataringaya was to become one of the early victims of the Idi Amin regime, as he was brutally murdered by Amin’s soldiers on September 18, 1972 at the age of 42, a few months after Amin took over power.

Apparently he had quit politics and retired to his home village of Kantojo in the then Igara county in Bushenyi district, where Amin’s soldiers picked him up and whisked him off to his execution. A picture of him being led to his execution by Amin’s soldiers, aboard a military Jeep, is one of the few photographs that testify to Amin’s execution of perceived political opponents.

Family background

At his death Bataringaya left behind a wife, Edith, and eight children. Edith was, however, also murdered by Amin’s soldiers in 1977, fi ve years after her husband had been killed. With all the family property confi scated by Amin’s soldiers, the children were picked up the Catholic Church and raised at a convent in Mbarara diocese under Bishop Kakubi and other well-wishers. Today all the children are relatively doing well, with half of them in medical practice.

Basil Bataringaya was born and raised in Kantojo, Igara county, Ankole district. He was the son of the Ssaza Chief of Bunyaruguru, Marko Kiiza. He studied at Nyakasura School and St. Mary’s College Kisubi, before joining Makerere University College. After graduation he taught briefl y at Ntare School before joining politics