Candidate Profile Page

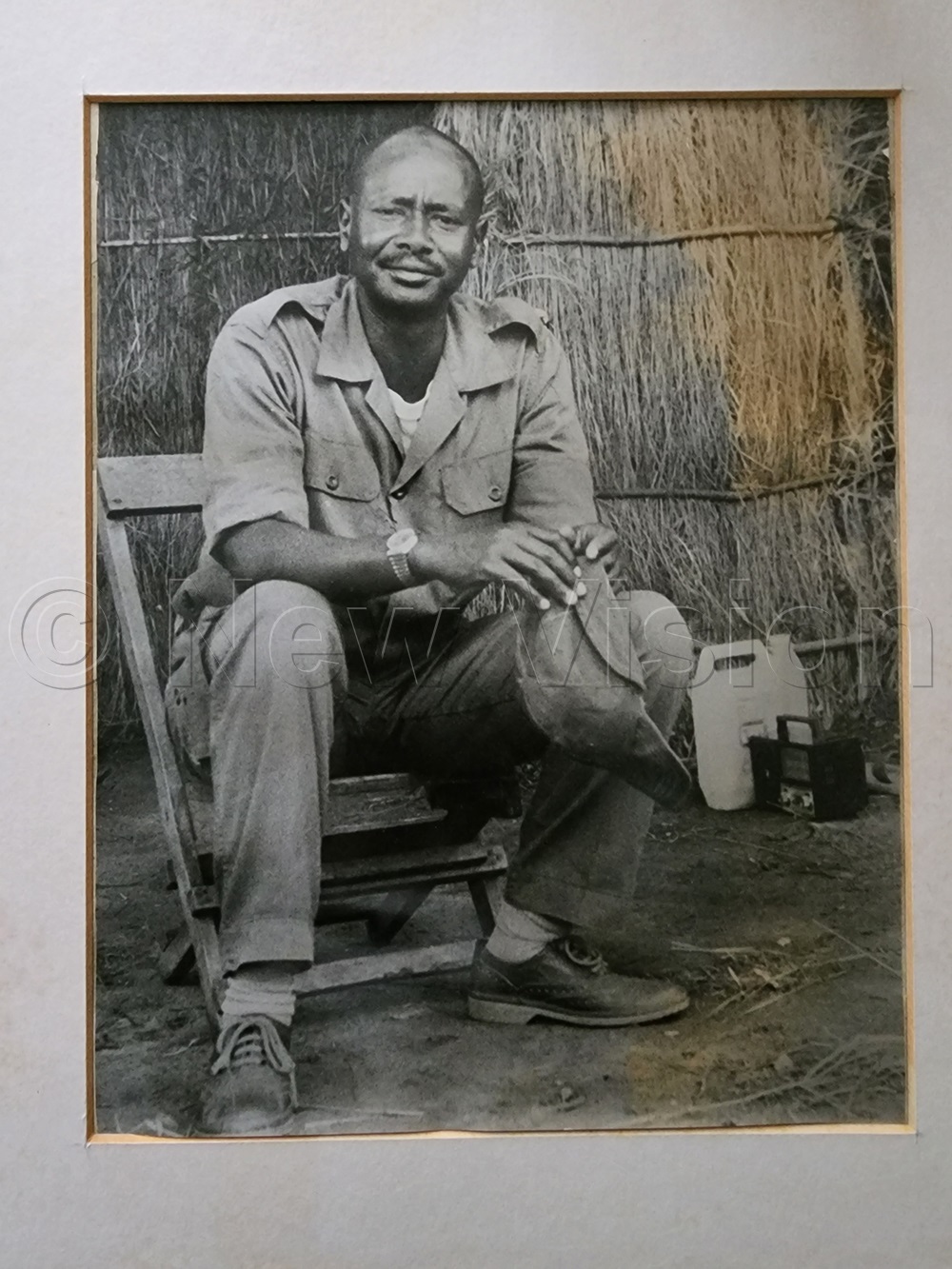

Mr Yoweri Kaguta Museveni

Picking up nomination papers on June 28, 2025, may have looked like a routine act for a politician. However, when that politician is Gen. Yoweri Museveni, it signalled something far weightier: The return of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) top gun — still firm, still strategic and still eager to consolidate a revolution he began.

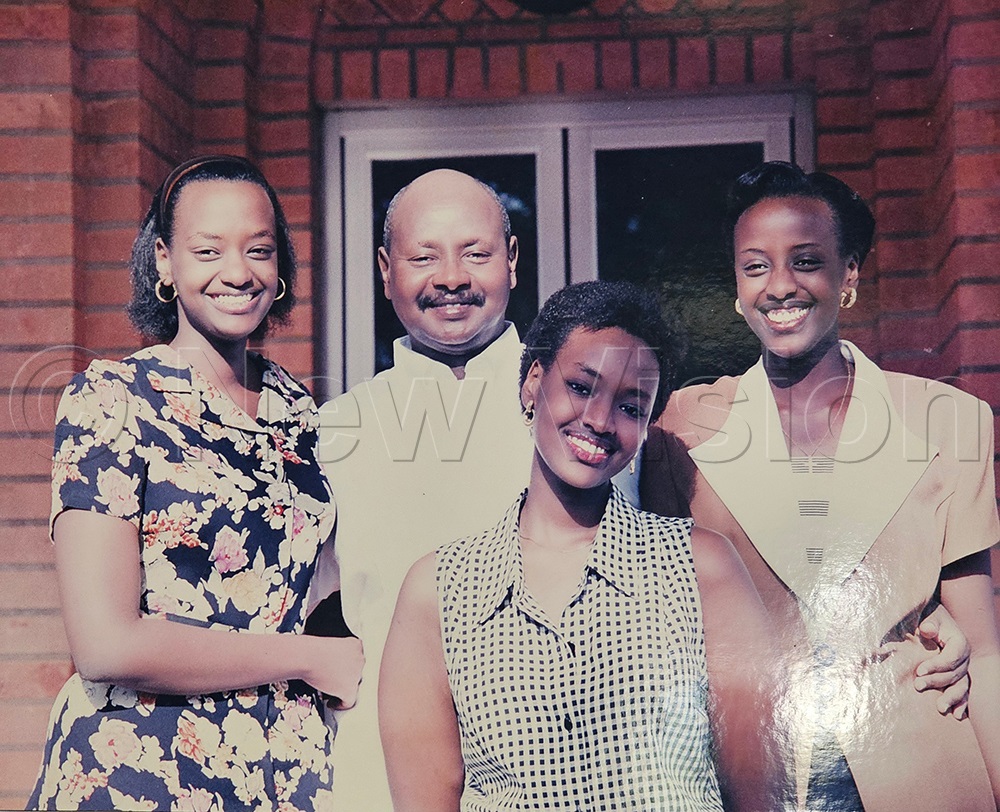

At 80 years old, the man known simply as “Mzee” or the “old man with a hat”, NRM officials said, is their best bet for the country’s top job ahead of the 2026 polls.

“People look at President Museveni as the national chairman of NRM and the party’s flag bearer, his role extends far beyond that. He went to the bush to liberate Uganda, and he has strong values as an individual, which he always passes on to the youths,” Emmanuel Lumala Dombo, the NRM director of communications, said, adding that the NRM members believe he is a gem within the party.

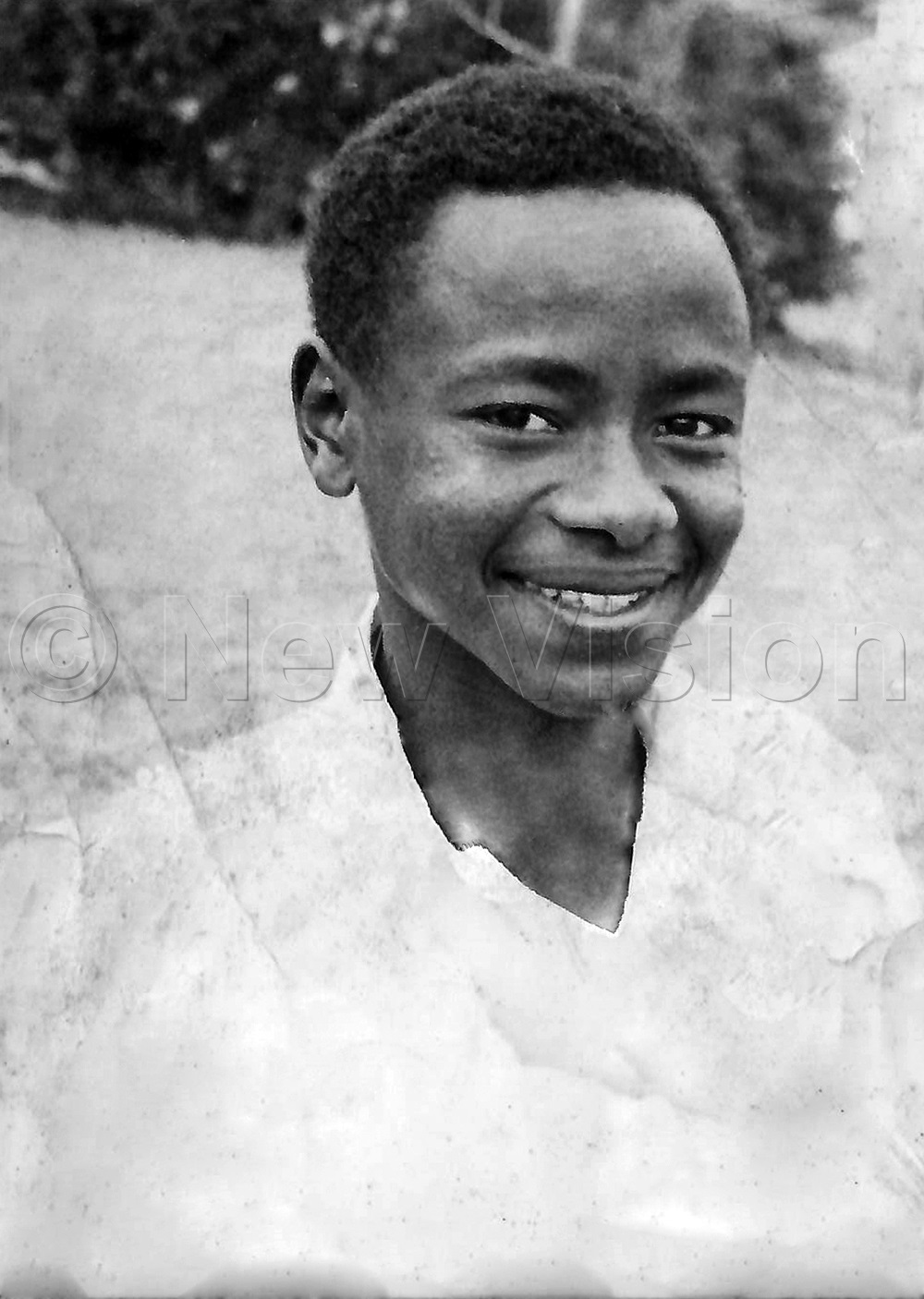

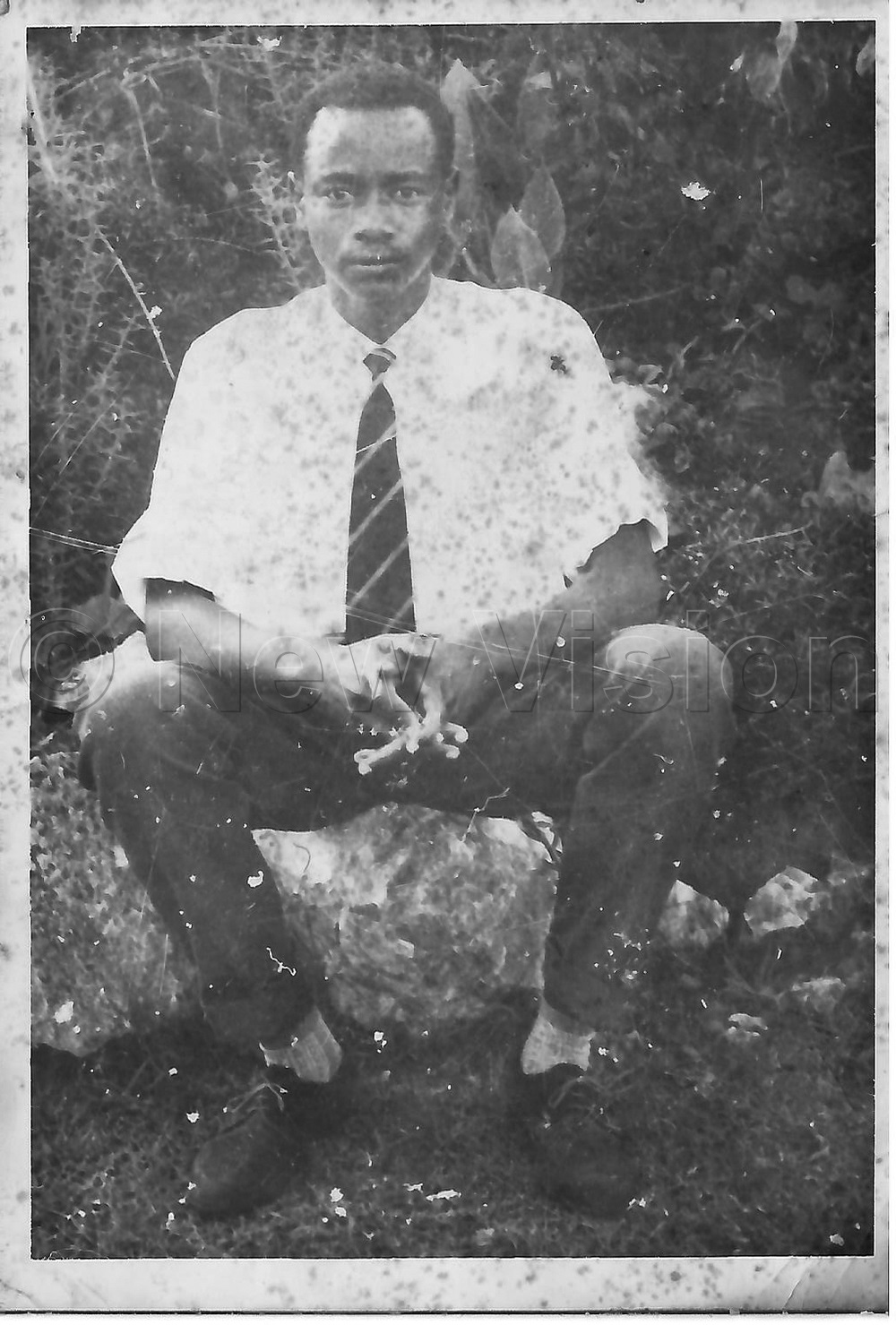

The young Museveni

Growing up in a humble rural family, this is the story of a man who grew up to become the beacon of hope not only for Uganda, but Africa too. Joshua Kato writes, picking adaptations from Sowing The Mustard Seed.

Like most children born in humble rural families, President Yoweri Museveni went through a typical rural childhood, going by accounts of those who knew him from childhood.

He walked barefoot and grazed cows at a tender age. He survived the hazards of walking around bushes barefoot, including the creepy snakes.

Eighty years ago, a bouncing baby boy was born to Amos Kaguta and Esteri Kokundeka. Museveni was born on September 15, 1944.

The parents

In his memoirs, Museveni writes that his father, Amos Kaguta, was born in 1916 in Ntungamo. His grandparents were born in Rujumbura, Rukungiri, while his great-grandparent, Kashanku ka Kyamukaaga, was born in Rushenyi.

At the time of Museveni’s birth, Ntungamo was a rural, peasant-dominated countryside with cattle kraals and bare farmlands.

Over the years, however, the farmlands have modernised with cattle keeping and matooke as the main enterprises.

From his own account, Museveni’s grandparents were great warriors. For example, Kashanku joined the army of the rulers of Rujumbura. At one time, he took part in a raid for cattle from the Banyabutumbi tribe. His father was also a champion wrestler.

He was named Museveni because at the time of his birth, Ugandans who had taken part in World War II, under the 7th Battalion, nicknamed Abaseveni, were returning to Uganda.

Baptism

On August 3, 1947, Museveni was baptised. On that day, he travelled together with his father Amos Kaguta and mother, Esteri Kokundeka, to Kikoni, Rwampara Church.

“I was almost three years old at the time. I remember we travelled by bus from Kakunamiriza and at about Mile 42 on the Mbarara-Kabale road, we alighted,” he says.

Unlike today, when the road is tarmacked, at the time, it was a narrow murram road, surrounded by mainly trees and banana plantations. At the time, transport was difficult because there were only two buses plying that route in the morning and in the evening. Museveni was not amused by the fact that the conductors of the buses were Indians, and most probably even the drivers.

In Kinoni, they stayed at the home of the late Erinesti Katungyi, who was then the chief of Rwampara. Museveni spent those days playing the ‘hill roll’ (gogolo) game on a gentle slope above the main house.

A few days later, baptism day came. Although he was smartly dressed in a nylon shirt and khaki shorts, he had no shoes.

“At some point during the church service, his father came and walked him to the priest, who sprinkled some water on him. With that, he had become a Christian. Days after the baptism, the family returned to Ntungamo by bus.

Starting school

Around 1950, the family moved out of their homestead at Ekirigyime Kabagyenda in Kikoni. As 1951 was drawing to a close, Kaguta moved his herd to Kafuunjo, which is only a mile from Ntungamo town. It is here that Museveni started his education.

In 1955, Amos Kaguta brought home another wife. According to Museveni, it was on account of the slow rate at which Esteeri was getting children.

“I could be considered an accessory in aiding and abetting the enterprise. I am the one who led the cattle for the bride price,” Museveni says.

Jane Beera, Museveni’s step-mother, subsequently gave birth to eight children.

In 1960, the family moved to Ruhuunga, Kashari. However, unfortunately, their cattle died, leaving only 30 weaners.

Surviving a snake

Typical of children in cattle-keeping areas, Museveni started looking after cattle at an early age. While grazing cattle, one day, he put a stick in a hole made by white ants. With the stick inside the hole, he was distracted as he looked at the cows.

Unknown to him, the hole had an occupant, and this was a snake.

“When I looked down again, I saw a small, slender snake standing up from the hole, trying to react to the aggression against its peaceful abode. I quickly withdrew my instrument of aggression and fled,” he says.

Museveni never reported this experience to his father because it surely would have earned him a beating.

22 heifers

“In 1961, we moved to Keigoshoora and later to Katebe. We lived in Katebe up to 1965, and that is when my father gave me my first herd of 22 heifers,” he remembers.

Museveni then moved the cows with his mother plus Caleb Akandwanaho, and sister Kajubiri to Akairungu in Rubaya sub-county. It was here that Museveni started teaching at Buruunga Primary School and Rukoni Primary School.

“Using part of the money earned from teaching, I bought the land in Rwakitura and we have been there since then,” he says. Rwakitura is found in Kiruhura district.

Kabamba attack: The spark that Luwero War

The road from Nyendo-Villa Maria to Ssembabule is now smoothly tarmacked. However, 38 years ago, it was a dusty murram road, with barely any human settlements.

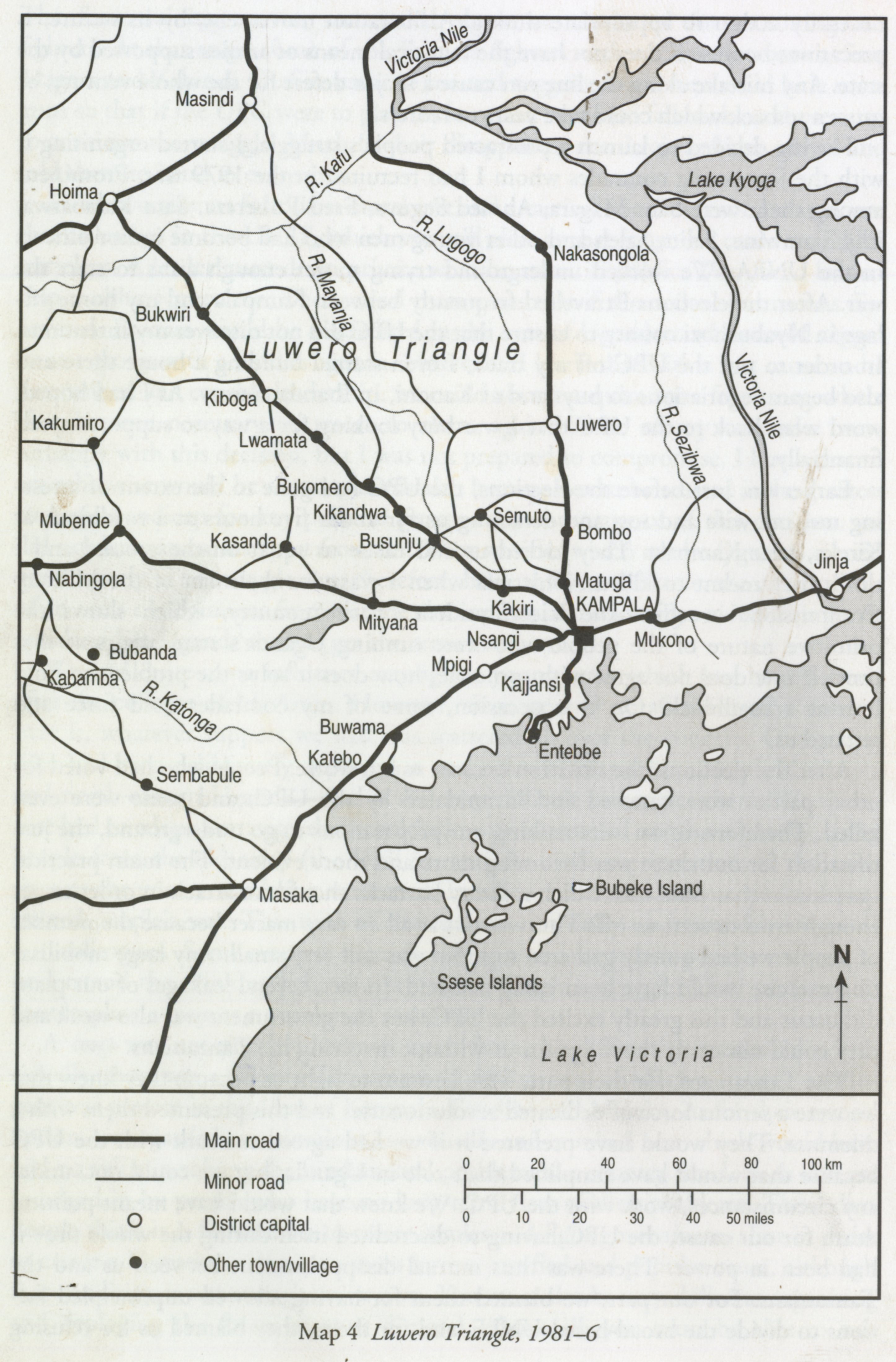

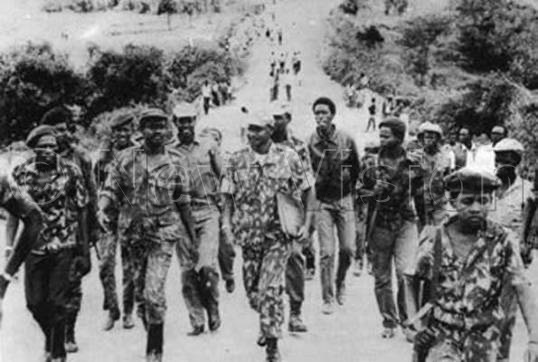

President Yoweri Museveni led a group of 41 men through this road in an old truck with one mission: to attack Kabamba Military Barracks. Having driven at dawn from Kampala, they scaled Nyendo and turned left at a Y-junction around Villa Maria, driving through Ssembabule en route to Kabamba. This act, risky as it looked, sparked off Museveni’s war in the Luwero Triangle.

On that evening of February 5, 1981, the secret combatants had their first incident at Katigondo. Today, it is a developed place with many shops and more residential houses surrounding the seminary. When this reporter tried to find out if any of the old residents of Katigondo remember seeing the Museveni group on that evening, nobody knew about it.

“There was no incident on our journey, until we had just passed Katigondo, about 12 miles from Masaka,” President Yoweri Museveni writes in his book, Sowing the Mustard Seed.

At Katigondo, one of the vehicles Museveni was using —a pick-up truck — got a puncture, and unfortunately, they had no spare tyre.

Did Museveni contemplate calling off the mission? That was out of the equation. At a distance, Museveni could see some homes. Walking briskly with a pistol in hand, he approached one of the houses and knocked on the door.

Nobody opened, probably in fear of the unknown. He then took a quick decision to walk back to Masaka, about 12km away, to seek help. Under the cover of darkness with almost no traffic on the road, Museveni walked up to Nyendo, near where TotalEnergies is located today. He then got a taxi that took him further to Masaka town.

Having been in national politics for some time, Museveni had a network of contacts all over. In Masaka, his target was Ruyondo, a former town clerk of the city.

“I am supposed to attend a wedding in Ssembabule, however, my car has got a puncture,” he told Ruyondo. Ruyondo believed the story. Subsequently, he handed the keys of a Peugeot 304, then a fairly famous car, to Museveni.

By the time they drove through Ssembabule town and Lwemiyaga to reach Kabamba, it was already morning. They attacked Kabamba at about 8:15am, but they did not get as many weapons as they expected. So, the war started without guns.

Plans for the bush

“If elections are rigged, I will go to the bush,” Museveni threatened! The threat subsequently turned into a reality.

According to Maj. Andrew Kangaho, who was living under the same roof with Museveni in the run-up to the 1980 elections, preparations for some mission started immediately after the elections.

After the elections, Museveni moved from Kololo to a house in Makindye. This was after Chris Rwakasisi, a minister in the new government, announced that all non-civil servants who were residing in government houses should vacate them. Museveni moved to a big house owned by John Wycliffe Kazoora in Makindye. The house sat on over five acres with a fence. It was, according to Kangaho, a perfect place to plan any clandestine activities.

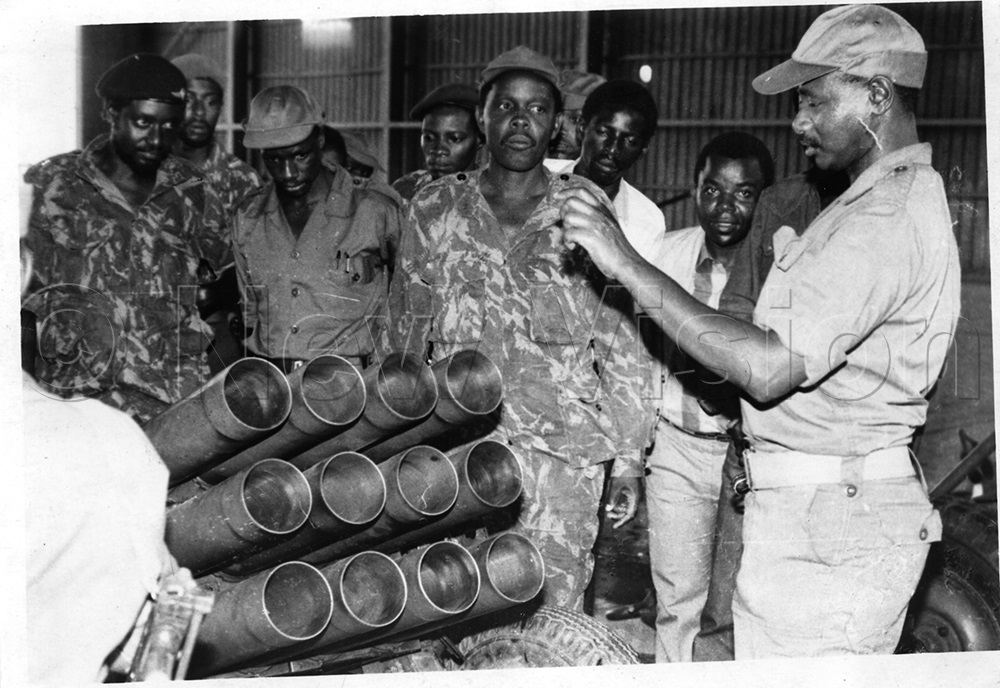

“There was a big cupboard in one of the rooms. One day, I opened it and saw guns there,” Kangaho says. He remembers that Rwigyema was in charge of this cupboard.

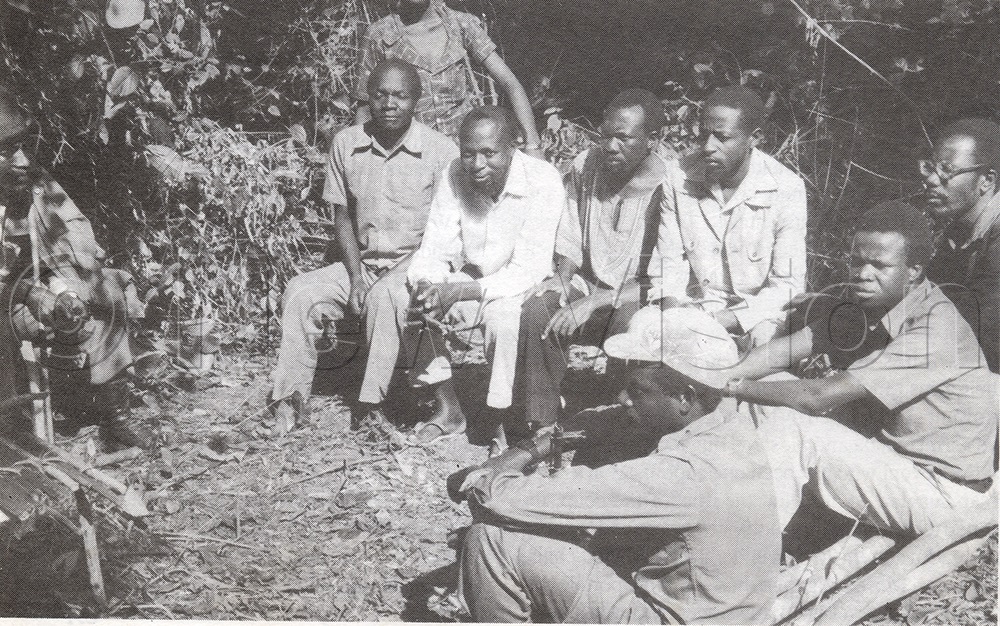

As January 1981 broke, at the big house, Museveni started meeting different groups of people for discussions.

He mainly used the upstairs room. Some of the people he saw included Julius Kihanda, Paul Kagame and Sam Magara. These were in addition to the earlier Museveni escort group that included Fred Rwigyema, Arthur Kasasira, Jack Mucunguzi, Robert Kabura and Aziz Bey.

“In early February, the group at the house was over 30 people. Then on February 4, the gate was opened and a pickup got in. They started loading it with things,” he says. On that day, Kangaho had been assigned to keep watch over the gate and told not to allow anybody inside.

Museveni was clearly going to the bush. However, there was still the question of his family. Moments later, Kangaho remembers seeing Alice Kakwano arriving on February 3, and leaving with Muhoozi Kainerugaba, then aged about seven and Natasha Museveni.

First Lady Janet Museveni momentarily remained with Patience Kokundeka and Diana Kyaremera. On February 4, Janet, too, left through Entebbe airport. The departure of Janet and the children brought relief to Museveni.

“Now that Janet and the children were out of danger, we were now free to act,” he said.

On February 5, the group gathered at Matthew Rukikaire’s house in Makindye. Kangaho’s observant eye did not miss what was happening.

“My sense told me that there was something cooking. Deep in me, I vowed to be part of it,” he says. However, he knew that there was no way he was going to be allowed to join because he was considered a child.

Museveni had arranged transport for the group earlier. It was a truck that could be covered, purposely to conceal its human cargo.

“At about 7:00pm, Lt Mule Muwanga carried out a roll call to board the truck. It left after 7:30pm,” Kangaho says. Museveni did not join the group in the truck, but used another vehicle driven by Lt Sam Magara.

The group covered Kampala-Masaka Road in the early hours of the night, before having a break.

Triggers off

At about 4:00am, the group stopped to get a final briefing before the attack. However, while the fighters allocated themselves four fighting formations, Kangaho was not allocated any unit! It was at this point that the Museveni group caught up with them again at the Rumegyere junction in Ssembabule, in the Peuget 304.

The plan was to attack at about 8:00am because the soldiers in the barracks would be on parade.

Museveni, being a known national leader, decided to stay in the back of the lorry to avoid being identified. Then, the small car zoomed past the lorry, followed by a gunshot. Then more shots.

Museveni believed that guns that belonged to disarmed FRONASA fighters had been stored there. So the objective was to capture the quarter guard and take out the arms.

Museveni needed information. The shooting went on for some time before somebody came to the lorry to give Museveni a situational report. Without radio calls, information came from a ‘runner’.

“Our fighters have attacked the quarter guard, but failed to access the armoury,” he told Museveni.

Although they did not enter the armoury, they collected many war materials, including three Tata trucks and three Land Rover vehicles. Museveni then directed the force to drive towards Mubende en route to Kiboga.

Museveni, unknown to the majority of his fighters, already knew that the group will set their bases north west of Kabamba, in Kiboga and Luwero districts. At Kyenjojo, they headed to Kagadi, then Karuguza and in the process, attacked Nsunga, Karuguza police stations and collecting more weapons. Museveni was amazed at the confidence and the tenacity of the fighters.

Driving quite fast, the force then entered Nkooko, then Ntwetwe, before reaching Kiboga at 2:00am.

The fighters even had time to enjoy a meal at a restaurant. “There is a restaurant where we stopped and he paid for food for all of us,” Kangaho says.

The force went to Kiboga Prison and released inmates. It was in Kiboga that Museveni officially made the declaration of war.

Why Kiboga and Luwero?

We are going to the bush. So, go and tell your leader that we have started what we promised,” Museveni told the District Commissioner. The force stayed around Kiboga through the next day and set their first headquarters near Bukomero in present-day Kiboga district.

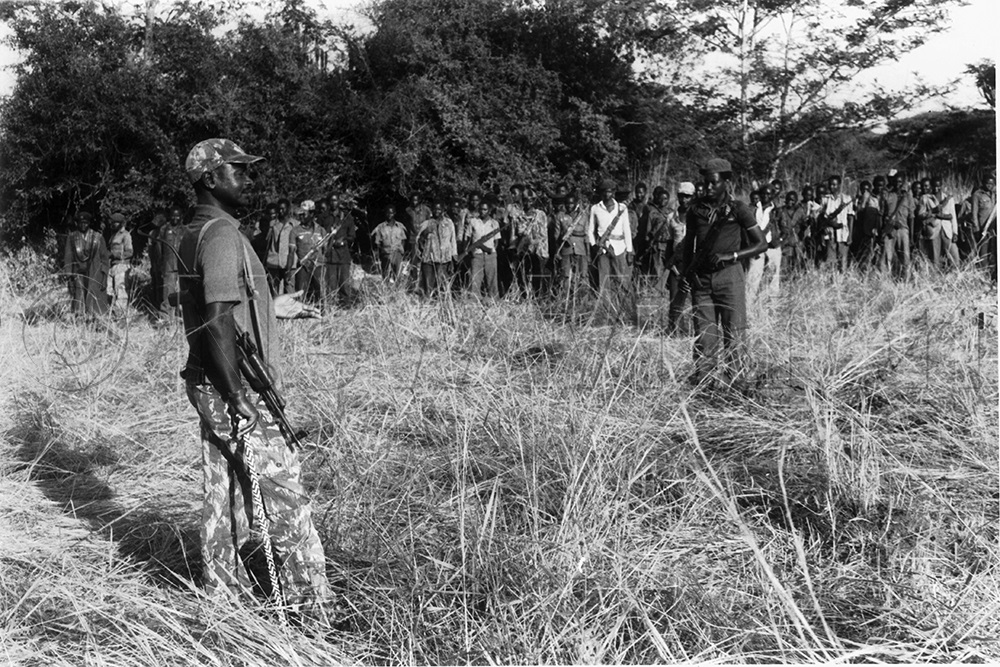

Museveni then called a meeting and created formations. The selected commanders included Elly Tumwine (section 2), Sam Magara (section 1), Hannington Mugabi (section 3) and Jack Mucunguzi (section 4). Others like Akanga Byaruhanga, Aziz Bbey and Mule Muwanga remained at the headquarters. The war had started!

There are many questions about why Museveni picked Luwero and not thicker hideouts like Mabira Forest in the east of Kampala or Kampiringisa Forest on Masaka Road in the south of Kampala. Close sources state that in his training as a guerrilla fighter, he learnt that a revolution like the one he planned depended on three main things: Availability of local population support, availability of food, mild natural cover like forests and rivers and, of course, weapons.

In the Kiboga area, Museveni already had several contacts, including Mzee Kagulire, while on the other hand, the late Sam Njuba had told him about the Semuto, Nakaseke and Kapeeka areas. The area also had food, including cattle in Ngoma, Kiboga and Kyankwanzi. This, Museveni knew, would give him some relief. Museveni had surveyed through the Ngoma area as way back as 1970, as he planned his anti-Amin campaign. He was now going to use it 11 years later. He set up the first headquarters at Kyekumbya in Kiboga.

The first headquarters at Kyekumbya, Mzee Kagulire’s place, however, he was attacked by a unit of Tanzanian troops. Museveni had driven to Bukomero by the time of the attack.

“I stayed at headquarters, and while there, we were attacked,” Kangaho says. “I heard a heavy explosion and then realised that we did not have such a weapon. I then saw our fighters rush to pick guns from the trucks and fight back,” he says. The unit and headquarters were dispersed. Rather than return to the attacked base, Museveni decided to head for Bukomero hills. He also decided to abandon the vehicles because they could not be concealed. The bush war had now kicked off.

The magical message that endeared masses to the struggle

The legendary Chinese revolutionary Sun Tzu put it clearly when he compared a guerrilla army to fish and water. He said for fish to survive, there must be water for them to swim in. Museveni got this clearly before he started the war in Luwero. His ‘fish’ (the fighters) had to have enough water — the population — to survive in.

He thus set on an ideological drive that ensured that there was always enough water, irrespective of the challenges.

Through his actions in the bush, there were traces of Mao Tse Tung, a legendary Chinese revolutionary; Ngoyen Giap, a Vietnamese general who adopted guerrilla tactics; Samora Machel of FRELIMO and Clausewitz, a Prussian general who fought against Napoleon Bonaparte, a French general, etc, all in one.

Museveni was not fighting by accident and without a vision. He had a clear ideology of how to wage this war. He called it the people’s war.

“As opposed to those who wanted a short conventional war, my plan was to carry out a war that involved and is owned by the local population,” he said in a statement to BBC on February 9, 1981.

Such was the strength of his message that even when things seemed challenging, his fighters simply retorted ‘Mzee anapanga,’ loosely meaning Mzee is planning something.

Clear message

According to Alhajji Abdul Nadduli, who joined Museveni around 1981, Museveni had a clear message for the population and knew exactly what the people wanted to hear.

“He resonated well with the population. He made them feel they were part of the war. He understood their needs, and this is why they supported it,” Nadduli said.

Museveni’s strategy included having the core group of fighters, including the High Command, of which he was chairman, a civilian political wing headed by Alhajji Moses Kigongo and Katenta Apuuli, Father Leo Sseguya, Walugembe and others. An external wing operated all around the world, and it included Kirunda Kivejinja, Amama Mbabazi, Ruhakana Rugunda, Eriya Kategaya and Dr Samson Kisekka and then Resistance Councils comprising of local opinion leaders in the war zone.

“When we were fighting Idi Amin, we had the misfortune of having our bases abroad. This partly prevented the population from feeling part of the revolution; hence, they never fully owned it,” he said.

In the early days of the war, Museveni used this message to set up the first stable base in Kikandwa, near Semuto. Major John Kaddu, now a retired NRA fighter, says when they first saw Museveni in 1981 after he moved from the Kiboga side, they saw many similarities with him.

“He talked about freedoms of speech and association; he told us about democracy and the stolen elections. He also talked about bringing back the Kabaka who had been exiled,” he says. He adds: “So, when he asked us to join him, we did not hesitate.”

Kaddu says that Museveni’s message also avoided sectarianism. “We never heard him promoting any tribe. All of us were fighters. This is why, even among the fighters, he avoided formal army ranks, until the end of the war,” he says.

His message was attractive to everybody, including graduates. In 1982, for example, the first large group of graduates joined him in the bush. Prominent among these was Gen. Kale Kayihura, the late Maj. Gen. Benon Biraaro, the late Gen. Aronda Nyakairima, the late Col Serwanga Lwanga and Brig. Phinehas Katirima.

Later, in 1985, Lt Gen. James Mugira, Brig. Charles Kisembo, Brig. Richard Kalemire, Brig. Sam Bainomugisha and others joined.

Introduction of RCs

The people’s approach included targeting prominent opinion leaders in an area, visiting them and convincing them to join the war.

The local people commonly referred to the fighters as abaana baffe (our sons) even when they did not have any close relatives in the unit.

His message to the population was: ‘This is your war, so fight it.’ This is how he introduced the Resistance Councils or RCs in the war zone.

In December 1981 in Timuna village, Luwero district (now Nakaseke district), Benjamin Kibuuka received three visitors at his home in the early hours of the night. One of these was a person he knew very well, a short, stout young man called John Zziwa, who had worked as his turnboy on his Bedford lorry.

The other two were Banyankore, though they spoke some Luganda dialect. He later identified one of them as Jackson Tushabe Bell, one of the first commanders of the NRA.

Under a tree about 50 metres from his house and without any lighting, the visitors sat with him and had a long conversation. Kibuuka had already heard about the war, but he had not thought about joining it.

“Mukama wange, ndeese abantu bano kubanga balwanirira gwanga. Bansabye omuntu omukulu asobola okukulembera ekitundu kino.” (I have brought these people because they are fighting for the freedom of Uganda. They want you to become the civilian leader of this area. They call them Resistance Councils).

Kibuuka had earlier lost his lorry to a UNLA soldier at Katikamu near Wobulenzi. He did not need further convincing to join the cause. On that night, Kibuuka became the first RC chairman of Nambega/Timuna village.

The NRA had already established similar structures in areas of Kapeeka and Semuto, where the war had started in February 1981.

“These were led by eminent people in the villages,” Kibuuka said.

The role of these ‘war committees’ was to mobilise support for the fighters. Among the fighters that Kibuuka mobilised were his brothers, who, unfortunately, died during the war. Kibuuka, just like many other RCs, also allowed the NRA to set up bases on their land, as long as it was safe.

In a previous interview, Kibuuka said they did not work for any pay, but for nationalism.

“We all knew that the elections had been rigged. So, when the Abayekera reached out to us, we had to support them,” he said.

Hassan Galiwango, now LC1 chairman Nambega village in Nakaseke district, had heard about abayekera ba Museveni as they were called in hushed voices for months.

From his village in Nambega, Nakaseke district, all that he and other people heard was that the rebels had attacked certain areas in Kiboga, especially Bukomero and Lwamata. He was in his youthful years.

The war had started, and, indeed, Galiwango and other residents had been seeing people fleeing from the direction of Semuto. But the attacks had never reached Nakaseke.

The fighters, led by Museveni, attacked Kabamba barracks on February 6. However, the attack was not decisive since the main objective was not achieved. The fighters withdrew to Kiboga through Mubende and set up their first bases around Bukomero and Lwamata. They gradually extended their lines to Semuto and Kapeeka, before setting up small bases near Nakaseke town, in the forests around Timuna village, Nambega, on the Nakaseke Kiwoko road towards November 1981.

“The first real sign of a rebellion came in December 1981, when a Uganda Transport Company (UTC) bus was hit by a land mine as it approached Nakaseke town from Kampala,” Galiwango says.

Later, residents were told that the mine had been laid to hit an army Land Rover that was coming from Kapeeka to Wobulenzi. Unfortunately, it hit the bus. The blast killed at least 20 people, most of them residents of Nakaseke.

Unknown to Galiwango and his fellow villagers, a group of the Abayekera ba Museveni was already near them, having met Kibuuka earlier. This very unit was based around the Kalasa and Waluleta, about 15 miles from Nakaseke.

The small group of the PRA, as they were called then, was commanded by the late Maj. Gen. Fred Rwigyema. There was also another unit of the PRA under Gen. Elly Tumwine that operated in the Kapeeka area — about 10 miles from Nakaseke town. These two groups are the ones that gradually reached out to Nakaseke town areas.

The Resistance Councils spread in all NRA operational areas across the country. Each of the RCs had 9 people. In 1986, when the NRA captured power, the RCs were transferred across the country as the primary village-level leadership arm.

“Their first task was to help government in distribution of scarce basic necessities like sugar, soap, tea leaves,” remembers Godfrey Walusimbi, the current LC chairman, Kanisa zone, Kawempe division. Walusimbi has been an LC chairman since 1990. The other big task for RCs was to fight localised insecurity in villages. This is when the first Local Defence Units were created.

Below is Museveni's profile

- 1944: Museveni was born in Ntungamo, Uganda.

- 1967: Graduated from the University of Dar es Salaam with a degree in political science and economics.

- 1971: Idi Amin seizes power; Museveni begins underground resistance activities.

- 1979: Museveni participated in the overthrow of Idi Amin; briefly served as defence minister.

- 1981: Formed the National Resistance Army (NRA) and launched a five-year guerrilla war against the Obote II regime.

- 1986 (Jan 26): NRA captured power; Museveni was sworn in as President of Uganda. The NRM government was established.

- 1995: A new Ugandan Constitution was enacted, emphasising decentralisation, human rights and term limits.

- 1996: Uganda held its first presidential elections under Museveni; he won by a large margin.

- 2000: Ugandans voted in a referendum to retain the Movement (no-party) system.

- 2005: Parliament removed presidential term limits, paving the way for Museveni’s continued presidency.

- 2006: Uganda held its first multiparty elections since 1986; Museveni won under the restored multiparty system.

- 2010: Uganda discovered significant oil reserves, sparking hopes of economic transformation.

- 2011: Museveni won his fourth term amid economic protests over rising inflation and cost of living.

- 2014: Uganda passed the National Development Plan II, accelerating infrastructure development.

- 2016: Museveni won another term; emphasised industrialisation and job creation through the “steady progress” slogan.

- 2017: Parliament removed presidential age limits, allowing Museveni to run beyond 75 years. 2020: Uganda was praised globally for its early and effective COVID-19 response.

- 2021: Museveni won re-election for a sixth term amidst a challenge from opposition leader Bobi Wine.

- 2024–25: Museveni prepared to contest once again, citing unfinished national transformation goals.