Ugandans thirsty for safe water

“When severe dry spells strike, the option is either to walk to the water sources or the water comes to the pastoralists. It is expensive to collect water for the animals, so, the cheapest option is to walk to the shores of Lake Kyoga,” Kunobere adds.

Residents at a borehole in Yumbe district. Some respondents in the Vision Group survey said they wake up before dawn and walk long distances to the nearest safe water source.

CITIZENS’ NEEDS

Water is life, and without it, living things cannot exist. However, few people in Uganda and Africa understand the problem of water scarcity better than Moses Okalayi, a resident of Magoro village in Magoro sub-county, Katakwi district.

The district is one of the most water-stressed areas in the country. “We cannot find water when we need it. We always have to walk long distances to find it,” Okalayi says, adding that weather extremes, such as water scarcity, are common in the district.

People and animals suffer in the same way, especially in the dry season. To make matters worse, the weather nowadays swings between two extremes.

“It can be extremely dry during the dry season and extremely wet during the rainy season,” Okalayi says, adding that the rainy season sometimes comes with floods and contamination of water sources, leading to the outbreak of diseases, such as dysentery, typhoid, cholera and malaria.

For many years, Katakwi has suffered from floods and drought in equal measure. Ideally, valley dams should be established to store the flood waters for irrigation and other uses in the dry season, but this is not happening at a satisfactory rate in the district and the rest of the Teso sub-region.

At the moment, Katakwi has Ongole, Osudan, Oumoi, and Oriau valley dams that have been established to store the excess water during the dry season. These are part of the six constructed in Teso sub-region by the Government and development partners.

Last year, floods swept across eight districts in Teso, destroying infrastructure like the Soroti-Kapujan road in Katakwi and the gardens.

The floods were so severe that 23-year-old Charles Olinga of Olobai village Ogera parish in Bugondo sub-county in Serere district paid the ultimate price. He drowned at Aboola bridge that had been submerged. In the neighbouring Kotido district, Adam Lokiru, a resident of Rengen sub-county, always considers himself lucky when his cattle get water, especially during the dry season.

“I always have to leave my home for four months when the nearby sources of water dry up,” Lokiru says, adding that he walks over 30km in order to find pasture and water.

Most of the conditions in Teso and Karamoja, where Kotido district is located, are similar to those in other districts in the cattle corridor that runs from western Uganda to the north-eastern tip of the country.

The conditions in the corridor are almost the same. About 300km to the south in central Uganda is Ronald Nkuruzinza, a cattle keeper in Ngoma sub-county, Nakaseke district.

Being a cattlekeeper, his water challenge is more compounded than that of Okalayi in Katakwi.

“We have good amounts of water, but when the dams dry up during severe dry spells, we run out of options,” Nkuruzinza says. In the past, they used to drive the herds hundreds of kilometres to Lake Kyoga for watering, but things have now changed.

“People have fenced off their land, which constrains movement of cattle,” Nkuruzinza says.

Following water

In Nakasongola district, also in the cattle corridor, James Kunobere, a resident, says the harsh weather conditions always trigger movement of pastoralists to Lake Kyoga, which is 60km away.

“There is plenty of pasture and water there,” he says, adding that the lake shores have enough pasture to feed their cattle for three months, after which they return home.

“When severe dry spells strike, the option is either to walk to the water sources or the water comes to the pastoralists. It is expensive to collect water for the animals, so, the cheapest option is to walk to the shores of Lake Kyoga,” Kunobere adds.

As the pastoralists move in an expedition that lasts up to a week, they encounter roadblocks in form of barbed wire fences, which results in conflicts and loss of property.

“There are people who have turned communal land into private property,” Kunobere says, adding that the creation of barricades is what is blocking pastoralists from escaping from the impacts of climate change.

Toro dilemma, community solution

Outside the cattle corridor is Bugaaki sub-county in Kyenjojo district where, for decades, residents have struggled to get water. To access water, they had to wake up before dawn and walk a distance of more than 15km to the nearest safe water source.

As a result, children would miss school, while women would lose several hours of productivity. Other residents who are not strong enough for the trek would resort to the contaminated swamps, which exposed them to water-borne diseases.

The suffering had gone on for long until 2022, when over 500 residents of Masese village in the sub-county started thinking outside the box. Through collective action, they refurbished a long-defunct shallow well that once served Masese and the neighbouring Burago village.

They pooled resources and hired a technical person to repair the well. For the first time in years, water flowed again. Cheers echoed as children, women, and elders filled their jerrycans without walking for miles.

But one shallow well, however, could not serve four thirsty villages. A larger vision was needed to solve this complex issue.

Armed with a new-found sense of unity, the community turned its eyes to long-term change. They held meetings and developed a clear and actionable plan — to ensure they are included in Rugombe town council’s plan for a piped water system — and they succeeded.

With the advice of the district woman MP, Faith Fulo Kunihira, the villagers approached the regional water umbrella office in Kyenjojo district. The water umbrella oversees Uganda’s decentralised piped water governance system across the country.

By May last year, the National Water and Sewerage Corporation, in co-ordination with local authorities, had started on the long-awaited water extension project. Pipes were laid, snaking across hills and through banana plantations.

The sound of machines working under the African sun was not just noise; it was a song of liberation. For the first time in history, they got piped water. At the moment, the final phase of the project, extending the pipes to residents’ homesteads, is underway.

Soon, residents will turn on a tap in their homes and see clean, safe water pour out. This is what they once prayed for. It is a dream come true.

In and around Kampala

Over 300km away, in Kampala — unlike the rural people who have to move long distances in search of water — the urban communities expect water to flow through the taps in their homes. However, this does not sometimes happen because of the glitches in the system of national water. In Katende village, Mpigi district, Dan Kiwanuka, a builder, says water has become a distant memory.

“I can’t tell you the last time I saw water in our village,” Kiwanuka says. “People have taps, yes, but no water comes out. It might trickle in once a month.” For Kiwanuka, whose livelihood depends on construction work, water is not just for drinking or bathing; it is the heartbeat of his job. Without it, he risks losing contracts or compromising on quality.

“On average, I spend over sh40,000 a day transporting water by bodaboda just to keep the work going,” he says. “If taps worked, I could be saving up to sh35,000 every day.”

Vision Group poll

It was against this backdrop that Vision Group conducted survey on the concerns of Ugandans about water access ahead of the 2026 elections. The issues covered are access to clean water, distance to water sources, drought and erratic weather patterns. They also mentioned the water challenges that they want government to address.

How poll was conducted

The Vision Group research team conducted an opinion poll between March and May, this year, covering 6,006 Ugandans across 58 districts and in all the 17 sub-regions. The survey, which targeted citizens above the age of 18, with valid national identity cards, sums up Ugandans’ environmental concerns: deforestation, wetland encroachment, pollution, climate change and waste management as some of the top issues that are affecting them.

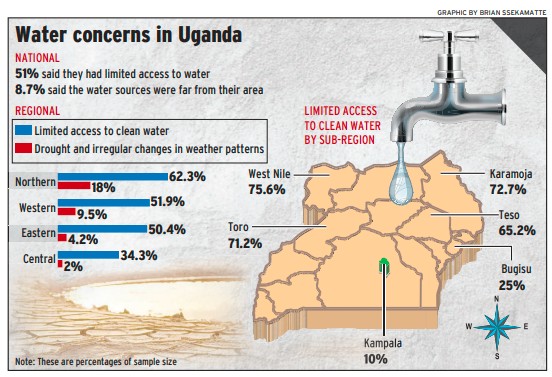

They thus called on the political leaders to deal with the issues. In the survey, 51% of the voters sampled said they had limited access to water while 8.7% said the water sources were far from their area.

At regional level, limited access to clean water was more pronounced in northern Uganda, at 62.3%. It was followed by western Uganda at 51.9%, eastern at 50.4% and central region at 34.3%.

At sub-regional level, the challenge of limited access to clean water was more prevalent in (71.2%) sub-regions. Teso had 65.2% of the voters saying they had limited access to clean water.

The sub-regions which had the least number of voters saying access to clean water is limited were Kampala, at 10% and Bugisu, at 25%. Water scarcity and irregular changes in weather patterns were more prevalent in northern Uganda, at 18% and western Uganda at 9.5%.

In eastern Uganda, only 4.2% of the voters said water scarcity was a threat, while in central, it was at 2%. At sub-regional level, existence of drought was most pronounced in Karamoja, at 66.7%, followed by Acholi at 27%.

Solutions by government

In Uganda, access to safe water refers to having a source within half a kilometre of a household, according to the World Health Organisation.

The Government goals for water supply and sanitation coverage refer to improved water supply with a source within 1.5km in rural areas and 0.2km in urban areas.

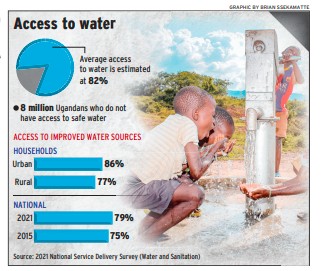

Alfred Okot Okidi, the permanent secretary of the water ministry, said households with access to improved water sources stand at 77% in rural areas, as opposed to 86% in rural areas.

This means — the average access to water is estimated at 82%. This translates to about eight million Ugandans who do not have access to safe water. There has been an improvement in water access within the last decade.

The access to improved water sources was estimated at 79% in 2021, according to the 2021 National Service Delivery Survey (Water and Sanitation). The same report states that 75% in 2015 had access to improved water.

While access to water is a political matter, the funding to the water and environment sector remains a challenge. In the last six years, the budget to the water and environment sector has been less than 3%.

In 2015, President Yoweri Museveni, with other world leaders, adopted the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or the development agenda to be achieved by 2030. SDG number 6 (water and sanitation) aims at providing universal access to safe and affordable water and sanitation.

This has been integrated into the five-year national development plans (NDP). Additionally, Museveni directed the water ministry to provide one water source per village.

“The number of villages without any safe water source reduced from 19,235 as of June 2020 to 13,274 as of June 2024,” Okidi said. There is also progress in water production storage capacity.

This has increased from 42.025 million cubic metres in the financial year 2019/2020 to 54.76 million cubic metres in the financial year 2023/24, against the NDPIII target of 76.82 million cubic metres.

The area under formal irrigation has significantly increased from 15,397 hectares in 2019/20 to 23,141 hectares in 2023/24, against the target of 27,424 hectares. Despite the achievements, the ministry faced challenges, including budget shortfalls. “The ministry is grappling with persistent budget shortfalls,” Okidi said.

“We received only 12% of the expected budget in NDPIII. The allocations over the five years came in a decreasing trend, contrary to the increasing demand for water and environment services, exacerbated by the intensifying impacts of climate change.”

The water and environment sector is facing concerns about service delivery, which is affecting the well-being of the citizens. This includes the delayed implementation of water for production, inadequate enforcement of Environmental Impact Assessment regulations, and poor wastewater management in urban centres.

There is need to address functionality of water sources, pollution of water bodies, rising urban flooding, limited access to climate finance, says the deputy head of Public Service, Jane Kyarisiima Mwesigwa.

For Uganda’s transformation to take shape, it was also observed that resilient ecosystems, equitable access to clean water and sanitation, and climate-smart infrastructure are critical.

There is an irrigation master plan in place and ongoing efforts to restore wetlands and forests, but challenges have persisted. The interconnectivity of water, climate change, energy and food production, as well as the fight against poverty, has been on the agenda of countries, including Uganda and the global agenda.

Locals of Toroma country, Katakwi district share a borehole with animals during a dry season.

Water as a human right

As far back as a decade-and-a-half ago, access to safe water is recognised as a human right by the UN. The right to water is considered essential for the full enjoyment of life and the realisation of all other human rights.

Diseases linked to sanitation, waste disposal

Dr Henry Mwebesa, the Director General of Health Services in the health ministry says 75% Uganda’s disease burden is preventable. He says diseases such as diarrhoea, dysentery, cholera, typhoid and skin infections are likely linked to water and sanitation services.

“WASH [Water, Sanitation and Hygiene] is a critical frontline defence against the spread of infectious diseases, which account for 30% of the health sector challenges,” Mwebesa says. He also says the water and sanitation-related diseases cost the Government sh530b annually, surpassing the sh511b allocated for medicines.

Water pollution

Lillian Idrakua, the commissioner of the water quality management department in the water ministry, says the quality of water shows how well or badly a catchment is managed. “The water was contaminated by organic materials two decades ago, but this has changed to chemical pollution,” Idrakua says, adding that this is likely to change for the worse with the increasing population, urbanisation and the changing climate.

Catchment management

The water ministry is making an attempt to decentralise water management across the country. Uganda is divided into four water management zones to manage water effectively. The water management zones are Kyoga, Upper Nile, Victoria and Albert.

The zones are based on catchment areas, which are regions where water drains to a common outlet, regardless of administrative boundaries. The catchment-based approach allows for integrated management of land, water and ecological systems, facilitating sustainable development, according to environment ministry.|

Citizens stand with nature

Hajara Lubega, resident of Kagote, Fort Portal: City leaders must prioritise sustainable waste management, protect wetlands, our main river, Mpanga, and green spaces from encroachment. Greening initiatives, such as tree planting, eco-friendly transport, and public awareness campaigns should not be occasional projects, but ongoing commitments.

Sam Ojok Omara, teacher trainer: We are alive because of the environment, but due to poverty, people have resorted to destroying the natural resources as a way of survival.

People are exploiting the environment to make ends meet, which is dangerous. I survived and studied by cutting down shea trees to burn charcoal to raise school fees. But I have started planting trees and telling people not to do the same.

Gladys Inyakula, a student in Arua City: Our leaders are good at making laws but the implementation is lacking. That is why the environment is not respected, and wetlands are encroached on.

What experts say

The Government is targeting universal access to safe water and sanitation for the people by 2030, says Alfred Okot Okidi, the permanent secretary in the water ministry. “The population is increasing, but funding to the sector is not increasing,” he says.

Okidi says they have made attempts to come up with innovations, and that currently, they are considering technologies, such as solar-powered pumps to get water from boreholes, which could be piped closer to people’s door-steps.

Water propels sustainable goals

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) — also known as the global transformation agenda or plan of action for people, planet and prosperity — are being implemented in Uganda.

There are 17 SDGs that cover an ambitious global agenda: from ending poverty to regaining peace and stability while leaving no one behind. SDGs are seeking to address poverty, hunger, health and well-being, quality of education, gender equality, clean water and sanitation, affordable and clean energy, decent work and economic growth, industry, innovation, and infrastructure.

They also seek to address inequality, sustainable cities and communities, responsible consumption and production, climate action, life below water, life on land, peace and strong institutions, and partnership for the goals. Water is central to the achievement of SDGs, which are interconnected.

This is seen from the rain-fed agriculture, which provides food security and income to most of Uganda’s population. The increased access to water will also help school children, especially girls, to stay in school. This is because it helps to improve menstrual hygiene. It reduces inequalities as women and girls spend a longer time fetching water, which is deemed to be their responsibility.

Apart from agriculture, industry sector is the biggest user of water, where it contributes to the prosperity of the country. This is because it is needed as a raw-material and it also helps in the industrial processes, such as heating, cooling and cleaning.

“It would increase the cost of doing business without water,” Onesmus Mugyenyi, the deputy director of Advocates Coalition for Development and Environment, a non-governmental organisation, said.

In sustainable cities or goal number 11, access to clean water, and rainwater harvesting are key areas to sanitation and effective wastewater management.

As opposed to the view that water is abundant, SDG number 12 is directed at the responsible use of water to promote sustainable production and consumption.

Water is critical when it comes to climate change action or SDG number 13, which is broadly about mitigation and adaptation.

As for life below water or SDG number 14, water is important for maintaining the water cycle, making water available in nature. Also, water is essential for keeping the health and productivity of forests, wetlands, mountains and drylands or biodiversity and the fight against desertification.

For peace or SDG number 16, water can bring conflict or co-operation, where water is either scarce or shared between communities and among countries. In the region, Uganda has been part of the 10 countries that negotiated the Nile Co-operative Framework Agreement, which has been ratified and took effect last year.

This aims at promoting the sustainable use of water among countries of the Nile basin. As for partnerships or SDG number 17, water is acting as a catalyst for collaboration and promoting integrated approaches to development.