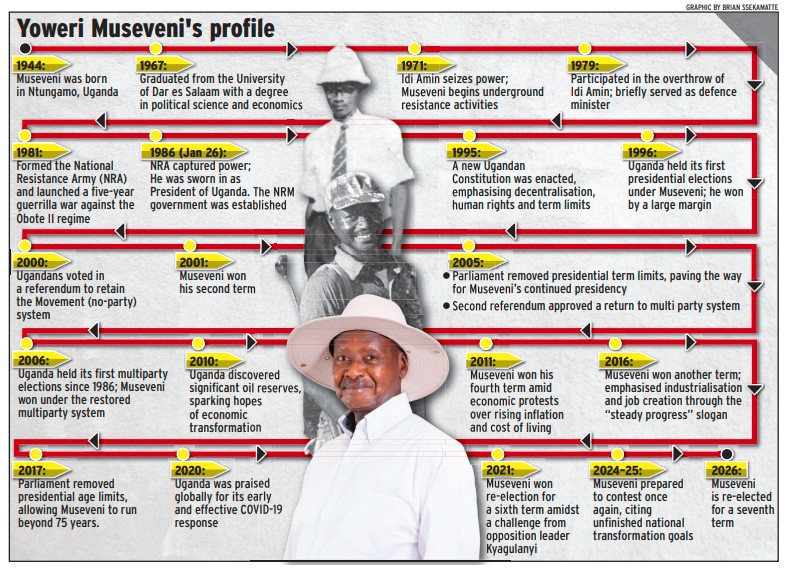

Return of the General: What makes the old man with a hat tick

At 81, the man known simply as “Mzee” in the corridors of State House or the “old man with a hat” in other circles, some politicians argue that Museveni’s political journey is akin to the story of Terminator, a blockbuster action movie by American actor, Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Growing up in a humble rural family, Museveni grew up to become the beacon of hope not only for Uganda, but Africa too. Museveni grazed cows at a tender age and walked barefoot, surviving hazards like stepping on deadly snakes.

KAMPALA - The January 15 polls, may have looked like a routine act for any politician. However, when results started to trickle in, Gen. Yoweri Museveni was in comfortably in the driving seat.

The results also signalled something far weightier: The return of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) top gun — still firm, still strategic, and still eager to consolidate a revolution he began.

At 81, the man known simply as “Mzee” in the corridors of State House or the “old man with a hat” in other circles, some politicians argue that Museveni’s political journey is akin to the story of Terminator, a blockbuster action movie by American actor, Arnold Schwarzenegger.

He never takes any chance. He never underestimates enemies. He works with everyone who is willing to co-operate with his movement. And like the mustard seed, his political vibe is always fertile.

The young Museveni

Growing up in a humble rural family, Museveni grew up to become the beacon of hope not only for Uganda, but Africa too. Museveni grazed cows at a tender age and walked barefoot, surviving hazards like stepping on deadly snakes.

Museveni was born on September 15, 1944 to Amos Kaguta and Esteri Kokundeka.

The parents

In his memoirs, Sowing the Mustard Seed, Museveni writes that his father, Amos Kaguta was born in 1916 in Ntungamo.

His grandparents were born in Rujumbura, Rukungiri, while his great grandparent, Kashanku ka Kyamukaaga was born in Rushenyi. At the time of Museveni’s birth, Ntungamo was a rural, peasant-dominated countryside with cattle kraals and bare farmlands.

Over the years, however, the farmlands have modernised with cattle keeping and matooke as the main enterprises.

Museveni’s grandparents were great warriors. For example, Kashanku joined the army of the rulers of Rujumbura. At one time, he took part in a raid for cattle from the Banyabutumbi tribe.

His father was also a champion wrestler. He was named Museveni because at the time of his birth, Ugandans who had taken part in World War II, under the 7th Battalion nicknamed Abaseveni were returning to Uganda.

Baptism

On August 3, 1947, Museveni travelled with his parents to Kikoni, Rwampara Church for baptism.

“I was almost three years at the time. I remember we travelled by bus from Kakunamiriza, and at about Mile 42 on the Mbarara?Kabale road, we alighted,” he says.

Unlike today, when the road is tarmacked, at the time, it was a narrow murram road, surrounded by mainly trees and banana plantations.

At the time, transport was difficult because there were only two buses plying that route in the morning and in the evening. Museveni was not amused by the fact that the conductors of the buses were Indians.

In Kinoni, they stayed at the home of the late Erinesti Katungyi, who was the chief of Rwampara. Museveni spent those days playing the ‘hill roll’ (gogolo) game on a gentle slope above the main house.

Although he was smartly dressed in a nylon shirt and khaki shorts, he had no shoes on his feet. During the church service, his father came and walked him to the priest who sprinkled some water on him, and he become a Christian.

Days after baptism, the family returned to Ntungamo, by bus.

Starting school

Around 1950, the family moved out of their homestead at Ekirigyime Kabagyenda in Kikoni.

As 1951 was drawing to a close, Kaguta moved his herd to Kafuunjo, a mile away from Ntungamo town. It is here that Museveni started his education.

In 1955, Amos Kaguta brought home another wife. According to Museveni, it was on account of the slow rate at which Esteeri was getting children.

“I could be considered an accessory in aiding and abetting the enterprise. I am the one who led the cattle for the bride price,” Museveni says.

Jane Beera, Museveni’s step-mother, subsequently gave birth to eight children. In 1960, the family moved to Ruhuunga, Kashari. However, unfortunately, their cattle died, leaving only 30 weaners.

My first herd

“In 1961, we moved to Keigoshoora and later to Katebe, where we lived up to 1965, and that is when my father gave me my first herd of 22 heifers,” he says.

Museveni then moved the cows with his mother plus Caleb Akandwanaho (Salim Saleh) and sister Kajubiri to Akairungu in Rubaya sub-county. It was here that Museveni started teaching at Buruunga and Rukoni Primary Schools.

“Using part of the money earned from teaching, I bought land in Rwakitura, and we have been there since then,” he says. Rwakitura is located in Kiruhura district.

Gen. Elly Tumwine

Kabamba attack

Thirty-eight years ago, the road from Nyendo-Villa Maria to Ssembabule was a dusty murram road, with barely any human settlements.

Museveni led a group of 41 men on this road in an old truck with one mission: To attack Kabamba Military Barracks. This act, risky as it looked, sparked off Museveni’s war in the Luwero Triangle.

On the evening of February 5, 1981, the secret combatants had their first incident at Katigondo.

“There was no incident on our journey, until we had just passed Katigondo, about 12 miles from Masaka,” President Yoweri Museveni writes in Sowing the Mustard Seed. At Katigondo, one of the vehicles Museveni was using —a pick-up truck — got a puncture and unfortunately, they had no spare tyre. Did Museveni contemplate calling off the mission? No. At a distance, Museveni could see some homes.

Walking briskly with a pistol in hand, he approached one of the houses and knocked on the door. Nobody opened, probably in fear of the unknown. He then decided to walk back to Masaka, about 12km away to seek help.

Under the cover of darkness with almost no traffic on the road, Museveni walked up to Nyendo. He then got a taxi that took him further to Masaka town.

Having been in national politics for sometime, Museveni had a network of contacts all over. In Masaka, his target was Ruyondo, a former town clerk of the city.

“I am supposed to attend a wedding in Ssembabule, however, my car has got a puncture,” he told Ruyondo, who believed the story and handed the keys of a Peugeot 304, to Museveni.

By the time they drove through Ssembabule town and Lwemiyaga to reach Kabamba, it was already morning. They attacked Kabamba at about 8:15am, but they did not get as many weapons as they expected.

Surviving a snake

One day, while young Museveni was grazing cattle, he put a stick into a hole that hads been dug by white ants. With the stick inside the hole, he was distracted as his eyes were on the cows. Unknown to him, inside the hole was a snake.

“When I looked down again, I saw a small slender snake standing up from the hole trying to react to the aggression against its peaceful abode. I quickly withdrew my stick and fled,” he says.

Plans for the bush

If elections are rigged, I will go to the bush,” Museveni had vowed. This had turned into a reality.

According to Maj. Andrew Kangaho, who was living under the same roof with Museveni in the run-up to the 1980 elections, preparations for the mission started immediately after the elections.

After the elections, Museveni moved from Kololo to a house in Makindye. This was after Chris Rwakasisi, a minister in the new government, announced that all non-civil servants who were residing in government houses should vacate them.

Museveni moved to a big house owned by John Wycliffe Kazoora in Makindye.

The house sat on over five acres and had a fence around it. It was, according to Kangaho, a perfect place to plan any clandestine activities.

“There was a big cupboard in one of the rooms. One day, I opened it and saw guns in there,” Kangaho says.

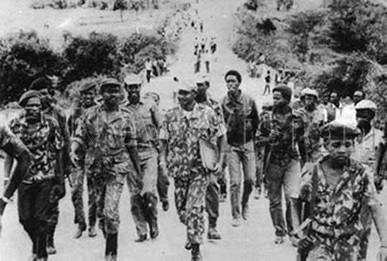

NRA march to Kampala 1986

He remembers that Fred Rwigyema was in charge of this cupboard. In January 1981, Museveni started meeting different groups of people for discussions in the big house. He mainly used the room upstairs.

Some of the people he saw included Julius Kihanda, Paul Kagame and Sam Magara.

These were in addition to the earlier Museveni escort group that included Rwigyema, Arthur Kasasira, Jack Mucunguzi, Robert Kabura and Aziz Bey.

“In early February, over 30 people were at the house.Then on February 4, the gate was opened and a pick-up drove in. They started loading it with things,” he says.

On that day, Kangaho had been assigned to keep watch at the gate and told not to allow anybody in.

Museveni was clearly going to the bush. However, there was still the question of his family.

Moments later, Kangaho remembers seeing Alice Kakwano arriving on February 3, and leaving with Muhoozi Kainerugaba, then aged about seven and Natasha Museveni.

Mrs Janet Museveni momentarily remained with Patience Kokundeka and Diana Kyaremera. On February 4, Janet, too, left through Entebbe Airport. The departure of Janet and the children brought relief to Museveni.

“Now that Janet and the children were out of danger, we were now free to act,” he said. On February 5, the group gathered at Matthew Rukikaire’s house in Makindye.

Kangaho’s observant eye did not miss what was happening. “My sense told me that there was something cooking. Deep inside me, I vowed to be part of it,” he says.

However, he knew he would not be allowed to join because he was considered a child. Museveni had arranged transport for the group earlier. It was a truck, that could be covered, purposely to conceal its human cargo.

“At about 7:00pm, Lt Mule Muwanga carried out a roll call, to board the truck. It left after 7:30pm,” Kangaho says. Museveni did not join the group in the truck, but used another vehicle driven by Lt Sam Magara. The group covered Kampala-Masaka road in the early hours of the night, before having a break.

First trigger

At about 4:00am, the group stopped to get a final briefing before the attack. However, while the fighters allocated themselves four fighting formations, Kangaho was not allocated any unit! It was at this point that the Museveni group caught up with them again at the Rumegyere junction in Ssembabule, in the Peuget 304.

The plan was to attack at about 8:00am because the soldiers in the barracks would be on parade. Museveni, being a known national leader, decided to stay in the back of the lorry, to avoid being identified.

Then, the small car zoomed past the lorry, followed by a gunshot. Then more shots. Museveni believed that guns that belonged to disarmed Front for National Salvation (FRONASA) fighters had been stored there.

So, the objective was to capture the quarter guard and take out the arms. Museveni needed information. The shooting went on for some time before somebody walked up to the lorry to give Museveni a situation report. Without radio calls, information came from a ‘runner’.

“Our fighters have attacked the quarter guard, but failed to access the armoury,” he told Museveni. Although they did not enter the armoury, they collected many war materials, including three Tata trucks and three Land Rover vehicles.

Museveni then directed the force to drive towards Mubende en route to Kiboga. Museveni, unknown to majority of his fighters, already knew that the group would set their bases north west of Kabamba, in Kiboga and Luwero districts.

At Kyenjojo, they headed to Kagadi, then Karuguza and in the process, attacking Nsunga, Karuguza police stations and collecting more weapons. Museveni was amazed at the confidence and the tenacity of the fighters.

Driving quite fast, the force entered Nkooko, then Ntwetwe, before reaching Kiboga at 2:00am. The fighters even had time to enjoy a meal at a restaurant. The force went to Kiboga Prison and released inmates. It was in Kiboga that Museveni officially made the declaration of war.

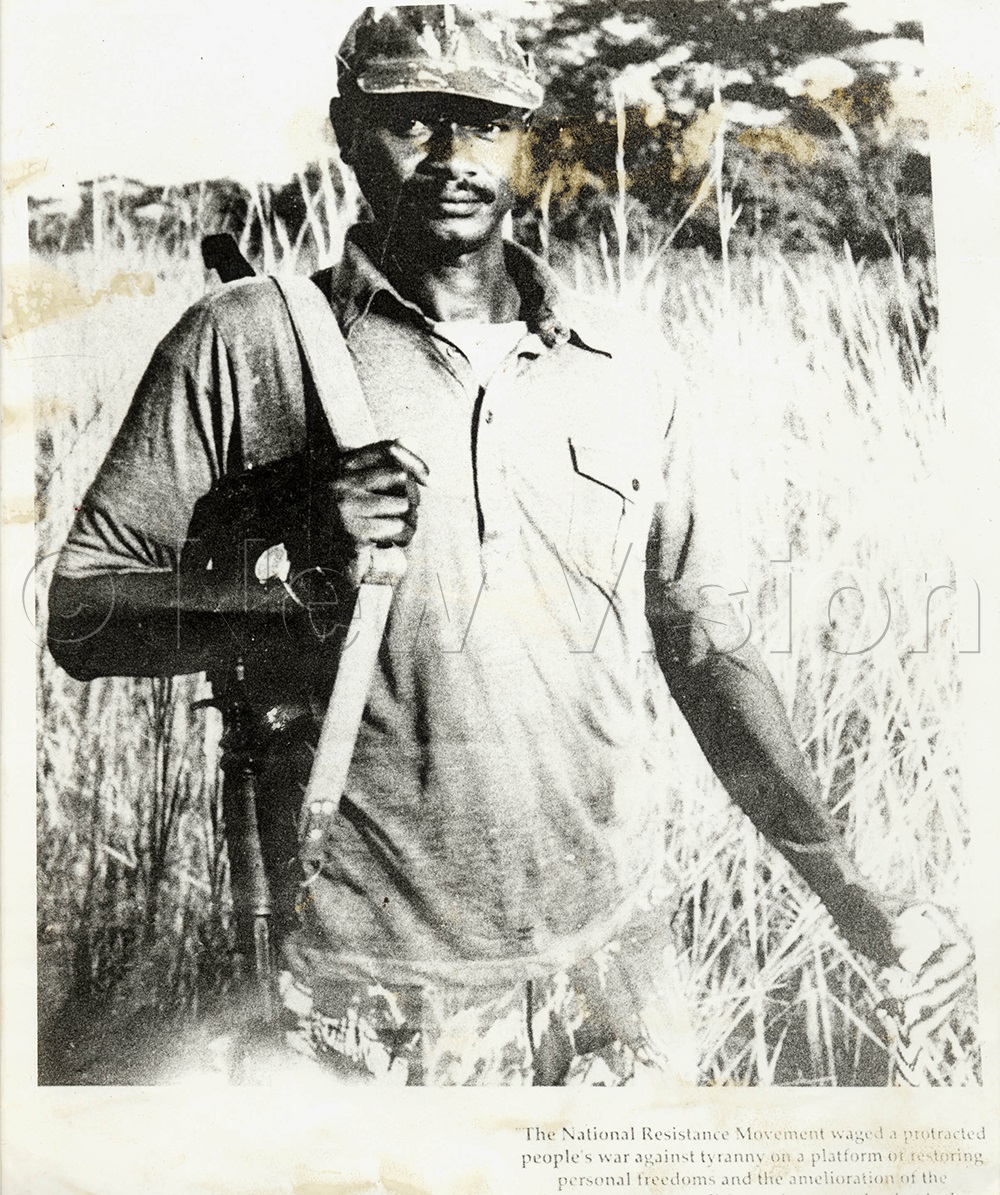

NRA Yoweri Kaguta Museveni seen in Bulemezi in 1984.

Why Luwero?

“We are going to the bush. So, go and tell your leader that we have started what we promised,” Museveni told the district commissioner.

The force stayed around Kiboga through the next day and set up their first headquarters near Bukomero in present-day Kiboga district. Museveni then called a meeting and created formations.

The selected commanders included Elly Tumwine (section 2), Sam Magara (section 1), Hannington Mugabi (section 3) and Jack Mucunguzi (section 4).

Others like Akanga Byaruhanga, Aziz Bbey and Mule Muwanga remained at the headquarters. The war had started.

There are many questions about why Museveni picked Luwero and not thicker hideouts like Mabira Forest in the east of Kampala or Kampiringisa Forest on Masaka Road, south of Kampala.

Close sources say that in his training as a guerrilla fighter, he learnt that a revolution like the one he planned depended on three main things: Availability of local population support, availability of food, mild natural cover like forests and rivers and weapons.

In Kiboga area, Museveni already had several contacts, including Mzee Kagulire while on the other hand, the late Sam Njuba had told him about Semuto, Nakaseke and Kapeeka areas.

The area also had food, including cattle in Ngoma, Kiboga and Kyankwanzi. This, Museveni knew would give him some relief. Museveni had surveyed the Ngoma area way back in 1970, as he planned his anti-Amin campaign.

He was now going to use it 11 years later.

He set up his first headquarters at Kyekumbya in Kiboga. At the first headquarters at Kyekumbya, Mzee Kagulire’s place, however, he was attacked by a unit of Tanzanian troops.

Museveni had driven to Bukomero at the time of the attack. “I stayed at the headquarters, and while there, we were attacked. I heard a heavy explosion and then realised that we did not have such a weapon. I then saw our fighters rush to pick up guns from the trucks and fight back,” Kangaho says.

The unit and headquarters were dispersed. Rather than return to the attacked base, Museveni decided to head for Bukomero hills. He also decided to abandon the vehicles because they could not be concealed. The bush war had now kicked off.

Mao’s doctrine

The legendary Chinese revolutionary Sun Tzu put it clearly when he compared a guerrilla army to fish and water. He said for fish to survive, there must be water for it to swim in.

Museveni got this clearly before he started the war in Luwero. His ‘fish’ (the fighters) had to have enough water — the population — to survive in.

He thus set out on an ideological drive that ensured that there was always enough water, irrespective of the challenges.

Through his actions in the bush, there were traces of Mao Tse Tung, a legendary Chinese revolutionary, Vo Nguyen Giap, a Vietnamese general who adopted guerrilla tactics; Samora Machel of Front for the Liberation of Mazambique (FRELIMO) and Clausewitz, a Prussian general who fought against Napoleon Bornaparte, a French general, etc, all in one.

Museveni had a clear ideology of how to wage this war. He called it a people’s war. “As opposed to those who wanted a short conventional war, my plan was to carry out a war that involved and is owned by the local population,” he said in a statement to BBC on February 9, 1981.

Such was the strength of his message that even when things seemed challenging, his fighters simply retorted “Mzee anapanga”, loosely meaning Mzee is planning something.

According to Haji Abdul Nadduli, who joined Museveni around 1981, Museveni had a clear message for the population and knew exactly what the people wanted to hear.

“He resonated well with the population. He made them feel they were part of the war. He understood their needs, and this is why they supported it,” he said.

Museveni’s strategy included having the core group of fighters, including the High Command, of which he was chairman, a civilian political wing headed by Haji Moses Kigongo and Katenta Apuuli, Father Leo Sseguya, Walugembe and others. An external wing operated all around the world, and it included Kirunda Kivejinja, Amama Mbabazi, Ruhakana Rugunda, Eriya Kategaya and Dr Samson Kisekka, and then there were the resistance councils comprising local opinion leaders in the war zone.

“When we were fighting Idi Amin, we had the misfortune of having our bases abroad. This partly prevented the population from feeling part of the revolution, hence they never fully owned it,” he said.

In the early days of the war, Museveni used this message to set up the first stable base in Kikandwa, near Semuto. Maj. John Kaddu, now a retired NRA fighter, says when they first saw Museveni in 1981 after he moved from the Kiboga side, they saw many similarities with him.

“He talked about freedom of speech and association; he told us about democracy and the stolen elections. He also talked about bringing back the Kabaka who had been exiled,” he says.

He adds: “So, when he asked us to join him, we did not hesitate.” Kaddu says that Museveni’s message also avoided sectarianism.

“We never heard him promoting any tribe. All of us were fighters. This is why, even among the fighters, he avoided formal army ranks, until the end of the war,” he says.

His message was attractive to everybody, including graduates. In 1982, for example, the first large group of graduates joined him in the bush. Prominent among these was Gen. Kale Kayihura, the late Maj. Gen. Benon Biraaro, the late Gen. Aronda Nyakairima, the late Col. Serwanga Lwanga and Maj. Gen. Phinehas Katirima. Later, in 1985, Lt. Gen. James Mugira, Brig. Gen. Charles Kisembo, Brig. Gen. Richard Kalemire, Brig. Gen. Sam Bainomugisha and others joined.

The people’s approach included targeting prominent opinion leaders in an area, visiting them and convincing them to join the war.

The local people commonly referred to the fighters as abaana baffe (our sons) even when they did not have any close relatives in the unit.

His message to the population was: ‘This is your war, so fight it,’ This is how he introduced the resistance councils (RCs) in the war zone.