Midwife campaign sparks hope for safe motherhood

According to the 2022 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey, neonatal mortality has dropped by 18% over the past eight years. Yet, 22 deaths per 1,000 live births remains alarmingly high.

Atimango (centre) being attended to by Musabe (left) at Nyantonzi health centre. In rural areas, where decisions are made by men, women may delay getting medical care during pregnancy. (Credit: Jacky Achan)

Midwives at the frontline

As the sun sets behind the hills, a ghostly silence enveloped Nyantonzi Health Centre III, a facility at the Masindi-Hoima border.

Only two women were visible — one lying on a hard bench, the other seated beside her.

The facility felt abandoned with no medical staff in sight; the only signs of life came from children playing football nearby and others fetching water from a borehole downhill.

The health centre could easily be mistaken for a forgotten outpost. Yet, within its walls, life-and-death decisions unfold daily.

On this evening, a young woman suspected of being in labour was gently led into the examination room by Maureen Jackline Musabe, an intern midwife from Hoima Regional Referral Hospital, and Maria Najjemba, a midwifery adviser from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Uganda office.

The midwives were in Nyantonzi in May for a community dialogue to mark Midwifery Week and the International Day of the Midwife.

On learning that a mother was in distress next door, they rushed to help. Irene Atimango had arrived with her aunt, Evaline Tiko, after enduring pain for nearly 12 hours.

A nurse in Karongo had advised her to go directly to the health centre, but her husband insisted she return home, citing money constraints and work obligations.

He later sent a motorcycle when pressed but did not accompany her. Upon examination, the midwives discovered Atimango was not in labour but was 36 weeks pregnant with a severe infection.

She had not taken any scans, had no money, and the facility lacked the capacity to treat her.

She needed an urgent referral to Hoima Regional Referral Hospital. Atimango’s story is sadly common in rural Uganda.

Many pregnant women delay seeking care due to poverty, distance, a lack of support and cultural beliefs.

Like Atimango, they often cannot make decisions alone.

Their husbands control the finances and determine when, or if, they can travel for care. This delay between deciding to seek care and reaching a facility is known as the second delay, a major contributor to maternal mortality.

One story too many

Rosemary Ajuna, 29, from Hoima district, knows this pain too well. A single mother navigating her second pregnancy alone, she turned to a traditional birth attendant when labour began. She lacked money for hospital care. Hours passed with no progress.

“I was in pain and hoped she could help me deliver,” Ajuna recalled. “The entire day passed. By evening, I wasn’t even feeling the contractions anymore.”

Doctors in Hoima discovered she had suffered a uterine rupture. Ajuna lost both her baby and uterus. She will never bear children again. But this time, something changed.

Her case was classified as a near miss, a term for women who survive life-threatening complications during childbirth.

“At Hoima Hospital, at least four near-miss cases are recorded each month,” Principal Nursing Officer Evelyn Achayo said, most referred from lower-level health centres like Nyantonzi.

The power of dialogue

In Uganda, community dialogue after maternal near-miss cases is a powerful tool for change, helping communities reflect on delays in care and find solutions.

Each dialogue rests on three pillars: facility near-miss case review (NMCR), a no-blame clinical review. The second, maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response, is adapted to include lessons from near-miss cases.

In the third, community dialogue, midwives and members examine delays in seeking, reaching and receiving care.

NMCR findings are shared with district reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health, as well as maternal and child health focal persons, plus village health teams (VHTs), who mobilise households for dialogue.

Sessions bring 30–50 participants, VHTs, local and religious leaders, elders, transporters, bodaboda riders, women’s groups, male champions, midwives, clinicians, and, if she agrees, the survivor or a family member. Confidentiality is prioritised, focus is on solutions, not blame.

“In Hoima, dialogues lasted nearly three hours because people had so much to share,” midwife Emily Atria Bako said. “We expected 30 participants, but over 50 turned up.”

Midwife campaign sparks hope for safe motherhood

Choosing communities

In Hoima, four recent community dialogues were held in areas like Nyantonzi and Kyesiiga, chosen for their poor maternal outcomes and weak referral systems. Women often have low antenatal care attendance and face major barriers to timely care.

During the dialogues, participants highlighted key issues: rude or dismissive health workers, corruption and informal fees, lack of transport, high costs for tests, men’s reluctance to accompany women, poor male involvement in antenatal care and limited access to family planning.

Despite frustrations, the dialogues supported by organisations like UNFPA created space for honest conversations.

In one session, women noted their husbands refused to buy clothes for antenatal visits. Men acknowledged the neglect, with many pledging to change.

“These dialogues let us hear community concerns and share our perspective,” Evelyn Kanyunyuzi, the president of the National Midwives Association of Uganda, said.

“The second delay in accessing care is a challenge in Hoima, across Uganda, and globally. We can only solve it by closing the gap with communities.”

Dialogues are reinforced by family visits, for example, to women recovering from fistula, offering psychosocial support and broader learning.

In urban spaces like Hoima taxi park, midwives used announcements, flyers and walk-throughs to gather participants for discourse.

Crisis to prevention

The near-miss initiative goes beyond identifying danger; it’s about preventing it. Midwives continue care beyond the hospital.

According to the 2022 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey, neonatal mortality has dropped by 18% over the past eight years. Yet, 22 deaths per 1,000 live births remains alarmingly high.

After Ajuna’s traumatic experience, midwives visited her home with supplies, food, soap and sanitary pads. They supported her post-peratively and helped her access fistula repair surgery through a UNFPA-supported medical camp.

“This should never have happened to me,” Ajuna says. “If I had gone to the hospital earlier, my baby would be alive.”

Her story, and others like it, are now used in community dialogues to educate and inspire change, aiming to make hospital delivery the norm.

Kanyunyuzi noted that while the campaign is in its early stages, its potential is enormous: “The results we expect are big and life-changing.”

Bako said domiciliary midwifery, where midwives live within communities they serve, is the solution.

“Embedded midwives educate families, build trust, break harmful beliefs and improve care-seeking behaviour,” she said, emphasising that pregnancy is not just a woman’s responsibility; it is a shared one.

At Nyantonzi’s dialogue, something remarkable happened: men pledged to accompany their wives for antenatal visits, plan financially for childbirth and take greater responsibility in maternal care. Though seemingly a small shift, it could be the difference between life and death for expectant mothers.

A mother caring for her baby. Nyantozi locals have pledged to be more involved.

Localising global concepts

The maternal near-miss framework, introduced by the World health organisation (Who) in 2009 and formalised in 2011, was quickly adopted in Uganda, adapted to local realities.

Although not fully embedded in Uganda’s maternal and perinatal death surveillance and response (MPDSR) guidelines, near-miss (women surviving life-threatening complications during childbirth) reviews are now widely used in case reviews and quality improvement efforts.

“MPDSR reviews often carry emotional weight and blame,” Evelyn kanyunyuzi, the president of the national Midwives association of Uganda, said.

“Near-miss reviews, by contrast, showcase resilience and success. They energise teams. Sometimes mothers don’t even realise how close they came to dying, you’re running, doing everything possible, and saving her life. That’s powerful.”

Though still in its early stages, nMcR is viewed by midwives as a game-changer, recognising that maternal survival ultimately centres on their skills, mindset and commitment.

More midwives needed

Midwives in public service lead maternal care, managing deliveries, emergencies and reproductive health services, yet they are often excluded from disaster planning and decision-making.

“We need investment in training, emergency response, and wellness,” midwife association head Evelyn Kanyunyuzi said.

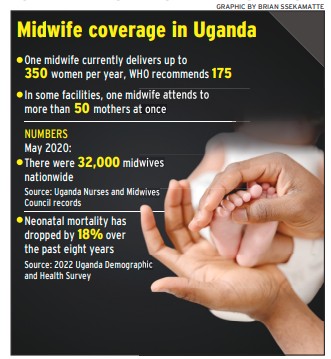

“One midwife in Uganda delivers about 350 women annually, double the WHO’s recommended 175. In some facilities, a single midwife serves over 50 mothers at once.”

As of May 2020, the Uganda Nurses and Midwives Council reported that around 32,000 midwives out of 70,167 registered practitioners serve a population of 48 million.

Staffing remains uneven, with rural areas critically short. “Uganda once prioritised training comprehensive nurses, assuming they could cover midwifery,” Bako said.

“This caused a shortage since they were registered only as nurses. Recruitment policies had to change.”

Today, midwifery-specific training is available through certificate, diploma, bachelor’s degree and master’s degree programmes at dedicated institutions, such as the Kalongo School of Nursing and Midwifery in Agago district and several universities.

During the recent community dialogue in Nyantonzi, residents shared a troubling reality: only two midwives serve the entire catchment area, alternating shifts every two weeks.

Overwhelmed and fatigued, midwives may become dismissive or harsh, leaving expectant mothers feeling unsafe.

“Ideally, a health centre III should have at least eight midwives,” Bako said, to which other stakeholders agree.

“This allows for proper shift rotation, one on evening duty, one on night duty, one off, and the rest balancing the schedule. Personally, I believe 10 would be ideal, but eight is the approved minimum.”

“We’re praying the Government increases the number of midwives,” one participant said.

“One person can’t attend to five or six women in labour at once. Some give birth on the floor. Others fear the scolding they’ll receive from overworked staff.”

Local leader Benon Drani called for Nyantonzi to be upgraded to a health centre IV.

This area has grown. It needs better facilities. Masindi district is too far to supervise this centre properly, and Hoima doesn’t have jurisdiction,” he said.

Despite the challenges, Drani expressed hope: “Today is the first time we’ve sat and exchanged ideas with midwives. If this dialogue continues, it will change our community.”

Midwives sit with locals, ask questions, listen and translate medical advice into local languages, bridging gaps that traditional outreach misses.

Change through discourse

Midwives are now tackling delays not just through treatment, but by changing mindsets before complications arise, using community dialogue. Near-miss cases are no longer isolated, they are investigated, followed up and used to spark change through community dialogue.

Midwives sit with locals, ask questions, listen and translate medical advice into local languages, bridging gaps that traditional outreach misses.

Led by midwives like Emily Atria Bako and others, the medical workers from Hoima, Kampala and beyond recently took health education to Nyantonzi, where Alur, Lugbara, Lunyoro and Kiswahili are spoken. Language barriers have long hindered access to care.

Dialogues revealed that men often neglect maternal health, women lack knowledge of danger signs and cultural beliefs discourage hospital deliveries.

“Most of our people are negligent,” Benon Jack Drani, the local council one (LC1) general secretary and teacher, said.

“We neglect responsibilities, including accompanying women for antenatal care.”

Many women still rely on traditional birth attendants (TBAs) and community members without formal training, but with locals’ trust.

However, TBAs, often lack knowledge of risk factors. Because they earn more from successful deliveries than referrals, they may delay sending women to hospitals even in emergencies.

According to the Maternal Health Review Uganda, poor referral and delivery practices among TBAs persist.

Despite training efforts, maternal mortality remains high in areas where TBAs are primary caregivers. Studies consistently show that deliveries by TBAs result in higher rates of maternal and newborn deaths compared to those handled by skilled health workers.

Unlike TBAs, midwives are formally trained and certified health professionals, with two to four years of standardised medical education.

They are central to Uganda’s maternal and newborn health system, equipped to conduct safe deliveries, provide antenatal and post-natal care, manage complications such as haemorrhage and perform newborn resuscitation.

Drani acknowledged the depth of the problem. “Our women have been suffering. Many of the challenges stem from our communities. We are rooted in traditional beliefs and men neglect their roles.

“We save money but rarely plan to use it for health or education. Girls drop out of school early. Teenage pregnancy is common,” the LC1 leader said.

Despite frustrations, the dialogues supported by organisations, such as the United Nations Population Fund, created space for honest conversations.

Dialogues are reinforced by family visits, for example, to women recovering from fistula, offering psychosocial support and broader learning.

In remote villages like Nyantonzi, where roads are rough, money is scarce and cultural beliefs run deep, midwives are visiting the community, listening and educating them.

They are bringing change and saving lives.

This story was written with support from Science Africa and the Africa Health Solutions Journalism Initiative.