Museveni 2026 bid starts

At 80 years old, the man known simply as “Mzee” in the corridors of State House or the “old man with a hat” in other circles, NRM officials said, is their best bet for the country’s top job ahead of the 2026 polls.

Museveni attended Kyamate Primary School, Mbarara High and, eventually, Ntare School, where he became known not just for academic sharpness, but for his fiery debates and iron convictions.

KAMPALA - Picking nomination papers on Saturday may look like a routine act for a politician.

But when that politician is Gen. Yoweri Museveni, it signals something far weightier: the return of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) top gun — still firm, still strategic and still eager to consolidate a revolution he began.

At 80 years old, the man known simply as “Mzee” in the corridors of State House or the “old man with a hat” in other circles, NRM officials said, is their best bet for the country’s top job ahead of the 2026 polls.

“People look at President While President Museveni is seen as the national chairman of NRM and the party’s flag bearer, his role extends far beyond that. He went to the bush to liberate Uganda and he has strong values as an individual, which he always passes on to the youths,” Emmanuel Lumala Dombo, the NRM director of communications, said, adding that the NRM members believe he is a gem within the party.

“We have always partaken of his wisdom and time will come when he will hand over to a younger generation, but as a party, we feel proud and happy to continue partaking of his wisdom,” he added.

On Thursday, the NRM electoral commission boss, Dr Tanga Odoi, said Museveni had already paid sh40m to express interest in two positions — party presidential flag bearer and party chairman — ahead of his physical appearance on Saturday to pick expression of interest forms.

He will return the forms on July 4 to seal his grand return to the presidential ring come 2026. In the language of Ugandan politics, this is more than a nomination — it’s a reaffirmation of a man’s pact with destiny.

The boy from Ntare

Museveni’s story began far from the presidential lecterns and military salutes, on the grassy hills of Ntungamo, where he was born in 1944 to Mzee Amos Kaguta and Esteri Kokundeka. His father, a soldier in the British colonial army’s 7th battalion, unknowingly handed down a legacy of discipline.

His mother, prayerful and patient, instilled in him moral clarity and an appetite for responsibility.

Museveni attended Kyamate Primary School, Mbarara High and, eventually, Ntare School, where he became known not just for academic sharpness, but for his fiery debates and iron convictions.

He led the Scripture Union, headed the debating society and began to speak about injustice in ways that unsettled even his elders. Friends say even as a teenager, Museveni didn’t just read books, he argued with them.

The making of a revolutionary

At the University of Dar es Salaam, Museveni’s youthful fi re met ideology. Here, under the intellectual influence of Mwalimu Julius Nyerere and a rising wave of African liberation theology, he was reborn as a revolutionary thinker.

Museveni became president of the University Students’ African Revolutionary Front, mingling with future presidents, generals, and Marxists.

He returned to Uganda with more than a degree. He returned with a vision. He would later found Front for National Salvation (FRONASA,) a movement that joined Tanzanian forces to help bring down Idi Amin in 1979.

When post-Amin politics turned chaotic again, Museveni went to the bush in 1981, leading the National Resistance Army (NRA) through a five-year guerrilla war that would change Uganda forever.

The statesman

When Museveni marched into Kampala in 1986, gun slung across his shoulder, rhetoric fiery, vision clear, he was met with guarded optimism. Uganda had been ravaged by coups, tribal politics and economic collapse.

Museveni promised a “fundamental change”— not a mere change of guards. He rolled up his sleeves, banned political parties in favour of “no-party democracy” and focused on reconstruction.

Peace returned, inflation dropped, education opened to all and roads were developed. In a continent littered with false dawns, Museveni’s four pillars — patriotism, social economic transformation, democracy and Pan-Africanism — shaped his journey into a General of African Resistance.

Even when his critics argued that he should cede ground and buffer his revolution with a political transition, he has always argued: The job is not yet done. His mission is to liberate Africa and create a centre of gravity that can safe-guard the continent from the over-bearing foreign interference.

The East African Community (EAC) integration and a possible African integration are the other twin agendas on Museveni’s political mission.

“There are two issues that are crucial for our future. These are political and economic integration of Africa. Our view is that Africa integration means three things: prosperity, security and fraternity,” Museveni said during the 32nd Ordinary Summit of African Union Heads of State in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in 2019. For him, integration is a vision that crosses borders.

Museveni’s eyes were never only on Uganda. A student of Nyerere, he believed deeply in Pan-Africanism. Under his leadership, Uganda has become a key player in regional security, sending troops to Somalia, mediating in South Sudan and helping stabilise eastern Congo.

He has been a strong advocate for East African integration, pushing for a political federation and economic unity across the region.

Museveni speaks often of “strategic bottlenecks”, inefficient trade routes and Africa’s failure to industrialise.

He believes African solutions must be homegrown. Whether lecturing global powers or mentoring young African leaders, Museveni remains a stubborn champion of African sovereignty.

To his supporters, he is a symbol of continuity, peace and strategic foresight. To critics, he’s an immovable mountain in Uganda’s political landscape. But even they agree — Museveni is not here by accident.

He is calculated, patient and ideological. Museveni often says you don’t abandon a plantation just as it begins to bear fruit.

Programmes such as universal education, Operation Wealth Creation and the Parish Development Model (PDM) are his tools to nurture that plantation. His hands remain on the plough.

Emmanuel Dombo

The party he built

The NRM is not just Museveni’s party, it was forged in war and tested in peace. From a rebel front in the Luwero bushes to a sprawling nationwide structure, the NRM has become Uganda’s most organised political outfit.

It has weathered internal dissent, constitutional amendments, generational challenges and opposition waves. Yet Museveni has kept the centre firm, building loyalty through vision.

He has outlasted rivals and embraced multiparty politics, a dispensation he strongly opposed in the past.

27 guns

When Museveni marched into Kampala on January 29, 1986 and was sworn in as President, few could have imagined that the man with a quiet voice and a revolutionary past would shape Uganda for decades to come.

He had led a bush war that started with only 27 guns and a ragtag group of fighters, without foreign bases or sophisticated backing.

Theirs was a local resistance, fuelled by peasants, shopkeepers and village elders, who believed in the simple, but powerful dream of reclaiming their country from chaos.

“We fought to free ourselves. To restore dignity. To end the madness,” Museveni would later say. His rise echoed the Cuban revolution in scope and spirit — scrappy, ideological and improbably successful. What Museveni inherited was a broken nation — its economy collapsed, its people traumatised, its institutions hollowed out.

The Government had become a machine of fear: extra-judicial killings, disappearances, economic collapse and the loss of all hope. But from his first speeches, Museveni signaled something different.

He spoke of reconciliation, of building a broad-based government and of a Uganda where religion, tribe and party would no longer define one’s fate. The bush war general preached harmony, and with time, many opponents have joined his yellow bus.

Todwong

Rebuilding from rubble

In every speech he delivers — whether in Kisoro or Kyenjojo — Museveni likes to remind his audience: “I cannot abandon the plantation when the harvest has just begun.”

And when one looks across the Uganda he has presided over since 1986, it’s hard to argue that fruit hasn’t grown. Under his stewardship, Uganda has changed visibly, structurally, and in many ways, irreversibly.

Under Museveni and the NRM, Uganda embarked on what was perhaps its most ambitious reconstruction since independence. The colonial economy, designed to extract, not empower, had crumbled by the 1980s. There was no real industrial base.

Commodities were scarce. Roads were riddled with potholes or simply impassable. Power blackouts were routine. The very idea of national unity seemed like a myth. But Museveni’s government got to work. Insecurity was tackled head-on. Soldiers were retrained, disciplined and professionalised.

Rebel groups were engaged or defeated. The era of arbitrary arrests and nightly gunfire began to fade. Then came the economy. Uganda embraced reforms — privatisation, trade liberalisation, fiscal discipline — and within a decade, growth took root. Since 1986, the size of Uganda’s economy has grown nearly tenfold.

GDP per capita has quadrupled. Inflation was tamed. Banks returned. Businesses opened.

As Museveni fixed the home front, he extended his influence across borders. His belief in Pan-Africanism wasn’t just academic — it shaped his foreign policy. Under his leadership, Uganda became a regional anchor for peace.

Museveni backed the African National Congress (ANC) during apartheid, hosting and training its fighters.

His government helped broker peace in Rwanda, aided in the resettlement of thousands of refugees and provided sanctuary at a time when Uganda itself had previously been a refugee-exporting nation.

Today, Uganda hosts over 1.5 million refugees, becoming a global model for humane and progressive refugee policy.

The Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF), once a guerrilla force, has since become a continental stabiliser, deploying peacekeepers to Somalia, South Sudan and DR Congo, among other nations.

Uganda’s boots remain on the ground wherever Africa bleeds. Museveni’s transformative governance has not gone unnoticed. Experts from New York University and the World Bank have ranked him among the most transformative post-independence leaders.

He was the first African president to receive the prestigious AfrikaVerein Award from the German-Africa Business Association.

Museveni holds honorary doctorates from universities across the globe — from the Humphrey School of Public Affairs (USA) to Makerere, Mbarara and the University of Dar es Salaam, where his revolutionary journey began.

Perhaps one of his most lauded achievements was Uganda’s fight against HIV/ AIDS. Where others flinched, Uganda led with honesty, community engagement and medical resolve.

And more recently, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Uganda received global acclaim — including from The Lancet medical journal, which ranked the country among the 10 best worldwide in managing the outbreak, and the best in Africa.

Mwambutsya

Continuity

As he enters yet another election cycle, Museveni can point to something few African leaders can: a nation at peace with itself, a country that functions, moves, builds and breathes.

From Karamoja to Kanungu, the guns have fallen silent. Rebel groups have either been defeated or reintegrated. Political stability, though contested, has endured.

Museveni’s personal life remains as grounded as his speeches.

He is married to First Lady Janet Kataha Museveni, herself a minister and advocate for education and morality, and together they have children and bazzukulu — the grandchildren and young Ugandans Museveni now often addresses directly in his paternalistic, but passionate tone.

As he picks up his nomination papers and steps into the 2026 political dance, Museveni stands not just as a candidate — but as an institution, a living archive of Uganda’s journey from bloodshed to nationhood.

To some, he is a liberator who overstayed. To others, he is the father of modern Uganda, a compass in uncertain times.

But to all, he is the old man with a hat — resilient, calculating and unyielding — whose imprint on the country is so deep it cannot be erased without rewriting the story of the nation itself. And as he often says, the harvest isn’t over. Not yet.

What analysts say

Prof. Ndebesa Mwambutsya said: “Ugandans are uncertain when there will be transition. There will be political anxiety about when Museveni will leave power and if he leaves, what will happen after being under the control of the majority party for such a long time.”

“What will the future be after Museveni? Maybe while picking forms, Museveni will say, this is my last time, but there will definitely be political anxiety. There is political anxiety because it is Museveni who is holding Uganda together. There has been fear of a failed transition from one national leader to another, raising the question, should people discuss transition and succession or should they just keep quiet?” he added:

Constitutional lawyer Peter Walubiri said: “President Museveni picking and returning nomination forms is not something new. What is new is what will happen if he does not pick the forms.”

The NRM secretary general, Richard Todwong said: “The party has received numerous calls and petitions requesting that President Museveni runs again in 2026. There is a difference between a leader, the people and the problems they face.

As leaders, your thinking must be different. You are the ones expected to guide the people out of poverty.

That is what President Museveni has executed well as the leader of the nation. That is why people are asking him to stand again as President. On our part as NRM, he is still our best choice.”

Milestones of Museveni and the NRM

1944: Museveni was born in Ntungamo, Uganda. 1967: Graduated from the University of Dar es Salaam with a degree in political science and economics.

1971: Idi Amin seizes power; Museveni begins underground resistance activities.

1979: Museveni participated in the overthrow of Idi Amin; briefly served as defence minister.

1981: Formed the National Resistance Army (NRA) and launched a five-year guerrilla war against the Obote II regime.

1986 (Jan 26): NRA captured power; Museveni was sworn in as President of Uganda.

The NRM government was established.

1995: A new Ugandan Constitution was enacted, emphasising decentralisation, human rights and term limits.

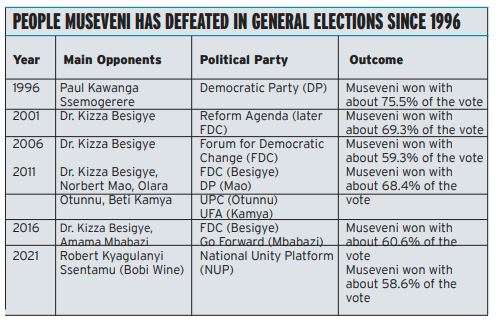

1996: Uganda held its first presidential elections under Museveni; he won by a large margin.

2000: Ugandans voted in a referendum to retain the Movement (no-party) system.

2005: Parliament removed presidential term limits, paving the way for Museveni’s continued presidency.

2006: Uganda held its first multiparty elections since

1986; Museveni won under the restored multiparty system.

2010: Uganda discovered significant oil reserves, sparking hopes of economic transformation.

2011: Museveni won his fourth term amid economic protests over rising inflation and cost of living.

2014: Uganda passed the National Development Plan II, accelerating infrastructure development.

2016: Museveni won another term; emphasised industrialisation and job creation through the “steady progress” slogan.

2017: Parliament removed presidential age limits, allowing Museveni to run beyond 75 years.

2020: Uganda was praised globally for its early and effective COVID-19 response.

2021: Museveni won re-election for a sixth term amidst a challenge from opposition leader Bobi Wine.

2024–25: Museveni prepared to contest once again, citing unfinished national transformation goals.

Additional reporting by Simon Peter Tumwiine