2026 Elections: Is there hope to kick corruption out of Uganda?

“When it comes to service delivery, for example, you may find that road works are underway, but instead of grading them to the required quality level, money is stolen, and in the end — poor quality work is delivered,” Chemutai says.

President Museveni launches the lifestyle audit campaign during the International Anti-Corruption Day celebrations at Kololo Independence Grounds in Kampala on December 9, 2021. The President was flanked by Deputy Inspector General of Government Dr Patricia Achan Okiria (left), Inspector General of Government Beti Kamya (second-left) and Rose Akello Lilly. The campaign is one of the tools in the war to eliminate corruption in Uganda.

CITIZENS' MANIFESTO

On October 13, 2023, former state prosecutor Simon Kigwana was convicted of corruption after soliciting a bribe while handling a case involving two complainants accused of threatening violence at Nabweru Magistrates’ Court in Wakiso district.

Kigwana was found guilty of taking sh200,000 from litigants Zam Ndagire and Octavious Kasumba, yet complainants are not required to pay for prosecution of their case.

On the arranged day of collecting the bribe, Kigwana was unaware that a trap had been set. Upon receiving the sh200,000 from Ndagire, a team from the State House Anti-Corruption Unit immediately swung into action and arrested the prosecutor.

His disgraceful eventual conviction by the Anti-Corruption Court in Kampala on two charges of corruption, and the subsequent sentencing to a fine of sh7m, was aimed at sending a message to other serving officers to desist from corruption, said Magistrate Esther Asiimwe in her judgment.

Kigwana’s case is just the tip of the iceberg of the huge corruption in Uganda, and his embarrassing conviction dealt yet another blow to public confidence in the justice system, as well as in other public institutions.

In Kabale municipality (western Uganda), former town clerk Christopher Ahimbisibwe and treasurer Godwin Asiimwe were, on March 18, last year, convicted on charges of causing financial loss, abuse of office and false accounting in relation to funds meant for the municipality’s development.

This was another embarrassing case of public officials involved in corruption and a reason for further erosion of public trust in institutions.

When President Yoweri Museveni launched the Parish Development Model (PDM) in February 2022, the aim was to increase household income and food security for Ugandans.

But some corrupt individuals saw it as an opportunity to steal. The President got to learn of the theft of PDM money and urged Ugandans to expose the individuals involved.

Under PDM, each parish receives sh100m per year, with each beneficiary getting sh1m.

The beneficiaries are required to return the funds (with 6% interest) after two years, to benefit another round of beneficiaries.

However, in Kiboga town council (Kiboga district), 10 would-be beneficiaries under Buzibweera PDM Savings and Credit Co-operative Society (SACCOS) were denied the opportunity when their chairperson, Michael Kakeeto, stole their sh10m.

He was found guilty of stealing the PDM funds meant for the SACCOS members.

The Anti-Corruption Court fi ned the convict sh1m and ordered him to compensate the SACCOS an equivalent of sh10m.

In addition, Kakeeto was barred from holding a public office for a period of 10 years. Such successful prosecutions are few and far between.

Victor Chemutai, a teacher in Kapchorwa district, agrees that corruption is ubiquitous in every sector and entrenched within communities.

“When it comes to service delivery, for example, you may find that road works are underway, but instead of grading them to the required quality level, money is stolen, and in the end — poor quality work is delivered,” Chemutai says.

He adds: “Even in the jobs sector, corruption is rampant and jobs are being sold. There have been cases in Kapchorwa where jobs were sold.”

What should be done?

Chemutai believes there is a lot of ground to cover considering that most of the people involved in corruption and bribery work as a team.

He suggests that the commercialisation of politics must be addressed, and that citizens should elect leaders who can be held accountable and are committed to addressing the issues affecting their communities.

Chemutai also says anti-corruption agencies should step up their efforts to curb corruption, by especially targeting the leaders who are part of the racket that perpetuates the vice.

Daniel Ssemyalo, a councillor representing workers in Kiboga district, says he feels demoralised and discouraged when he sees something that should be earned on merit being sold.

Geoffrey Kazinda (left), the former principal accountant in the Office of the Prime Minister, being escorted to the Anti-Corruption Court in Kampala back in the day over forgery and abuse of office.

He says corruption has severely undermined service delivery, adding that funds allocated for public services should benefit communities directly.

“Corruption affects all of us, and I strongly condemn it. The corrupt should be isolated. When someone pays a bribe to get a job, they are unlikely to deliver because they will be focused on recovering the money they paid.

If someone asks you for a bribe, report that person. And if someone offers you a bribe, reject it and also report that person,” Ssemyalo says.

For Gideon Akunyuk, a farmer in Kapelebyong district, giving culprits harsh punishments is the only solution to fighting corruption.

He says public officials found guilty of corruption should be hanged and all their assets confiscated.

Akunyuk says if society continues to handle the corrupt with kid gloves, Uganda will never win the war against corruption.

Vision Group survey

A comprehensive survey conducted by Vision Group between March and May, this year, across 58 districts in 17 sub-regions in the lead-up to the 2026 general election, indicates that corruption continues to be a pervasive challenge to service delivery.

The study sought to assess voter perceptions on key political, social and economic issues shaping the 2026 general election, and identify critical policy issues that citizens expect leaders to address.

It covered 6,006 eligible voters (aged 18 and above) through a stratified random sampling method, ensuring demographic and regional balance.

Approximately, one-third of the respondents reported having paid bribes, with the highest prevalence in eastern Uganda. According to the survey, bribery affects men, younger adults, and the self-employed disproportionately, while those with higher education or unemployment reported fewer experiences.

Petty corruption remains endemic, underscoring the need for sustained anti-corruption efforts across all sectors and regions.

The survey found that the majority of respondents (68%) — whether in rural or urban areas — believe that corruption is widespread, against the 9% who disagree with the perception.

Between 18% and 22% of the respondents said they were unsure whether corruption is widespread.

Generally, corruption is widely seen as a serious problem across all regions of Uganda: central (71%), northern (70%), western and eastern (both at 67%).

Only a small number of people in any of the regions (6%) believe corruption does not exist.

In terms of age, the belief that corruption is widespread in Uganda was found to be more resounding among younger people, particularly those aged 25 to 29, where 14.4% believe corruption is widespread.

With an increase in age, the number of affirmative responses over the prevalence of corruption was seen to gradually decline, with older adults (65 years and above) showing lower levels of concern.

Across all age groups, the number of people who said they do not know that corruption is widespread remains relatively low.

The poll named other key concerns including health services (53%), education (35%), poverty and roads (29%), employment (19%), water and sanitation (16%), national security (15%) and food services and livelihoods. Overall, the findings point to a national consensus that corruption is widespread.

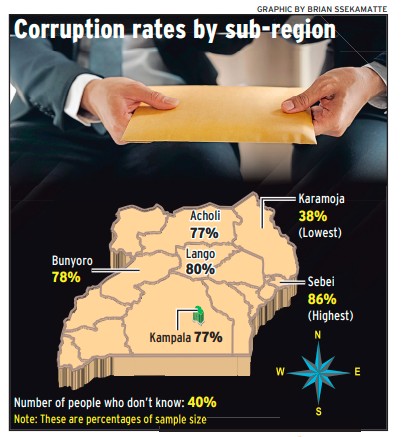

The perception of corruption being widespread is highest in sub-regions of Sebei (86%), Lango (80%), Bunyoro (78%), Acholi (77%), and Kampala (77%). Karamoja has the lowest number of people who believe corruption is widespread (38%), as well as the highest number of people who do not know (40%).

Ali Munira, the spokesperson of the Inspectorate of Government.

Paying bribes

Ali Munira, the spokesperson of the Inspectorate of Government, says services — such as getting or applying for a government job and accessing malaria drugs in health centres — are free of charge.

Consulting a doctor at a government hospital is also supposed to be free. However, ordinary Ugandans have admittedly had to bribe their way into getting what should, otherwise, be a free service.

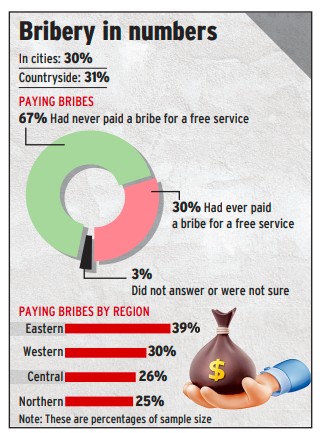

Respondents were asked whether they had ever paid a bribe for a service that should be free, and about a third of them (30%) responded in the affirmative — an indication that petty corruption is still common in access to public services.

The majority of the respondents (67%) said they had never paid a bribe for a free service, while 3% did not answer or were not sure.

Interestingly, bribery was found to have been happening both in cities (30%) and in the countryside (31%), pointing to the ubiquitous nature of the problem.

The experience of paying bribes differs per region, with eastern Uganda having the highest rate of people (39%) reporting they had paid a bribe. The gap is not so big per region: western (30%), central (26%) and northern (25%).

Age and education

The survey found that bribery reports decrease with age, dropping to less than 1% among people aged 60 and above. The high rates are seen in the 25-29 and 30-34 age groups, at 5.9% and 5.8% respectively.

The 35-39 age bracket follows closely at 5%.

The data shows a clear link between a person’s level of education and their experience with bribery. People with secondary education reported the highest rate of bribery at 6.3%, followed by those with primary education.

Those with university or post-graduate education reported fewer cases of bribery.

This, according to the survey, suggests that higher education may help people avoid situations where bribes are asked for, or it may make it easier for them to get services without paying bribes.

Similarly, people with no formal education reported the lowest bribery rate (1.9%).

“However, this may be because they have fewer dealings with formal government services, and not because corruption does not exist in their communities,” the report says.

People with no formal education reported the lowest bribery rate (1.9%).

Over the years, the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions (ODPP) — a government body which mainly takes criminal cases to courts — has handled many cases involving corruption.

ODPP spokesperson Jacquelyn Okui says members of the public should first and foremost desist from corrupt practices such as offering bribes for services.

“Those who also willingly receive bribes or gifts which they know are meant to induce them to favour the givers should desist from this practice because this encourages the bribing.

The public should also report all incidents of corruption to the Police or State House Anti-Corruption Unit for investigation. Thereafter, they should support investigations by giving these law enforcement agencies all the necessary information pertaining to corruption cases,” Okui says.

Bottom-up approach

The voices of the ordinary Ugandans feed into the concerns raised by the Inspector General of Government, Beti Kamya, that Uganda loses up to sh9.1 trillion annually to corruption.

That is around 12% of the 2025/2026 national budget. Kamya’s strategy to bring down this statistic is through cracking the whip on the small fish, as they are the ones who take bribes on behalf of their bosses.

This bottom-up approach to tackle systemic corruption involves tracking suspicious financial flows, starting with low-level public servants and moving up the chain to top government officials.

Kamya’s strategy aims at exposing corruption networks within the Government by following financial trails that, she says, often begin with junior staff and lead to powerful officials.

She says junior officers typically execute orders from seniors, but when accountability is demanded, the superiors evade scrutiny, making it difficult to trace corruption to the top.

In his national budget speech this year, President Museveni repeated his condemnation of corruption. He was, especially, critical of politicians using money to gain political support, saying the Government would introduce a raft of new measures to curb corruption.

What has been done

In his national budget speech this year, President Museveni repeated his condemnation of corruption. He was, especially, critical of politicians using money to gain political support, saying the Government would introduce a raft of new measures to curb corruption.

Some of the interventions will include conducting regular audits, encouraging whistleblowers to report any corruption, and using digital platforms in organisations such Uganda Revenue Authority to reduce human contact, which can limit opportunities for corruption.

Chief State Attorney Annet Namatovu Ddungu says the ODPP recovered over sh20b from convicts between the financial years 2022-2023 and 2024-2025.

She says the ODPP has also intensified efforts to recover money from other individuals recently convicted by the Anti-Corruption Court.

In July, this year, the Inspectorate of Government said the ombudsman had secured a 40.6% conviction rate of corrupt officials and recovered sh6b from them.

What do experts say?

Peter Wandera, the executive director of Transparency International Uganda — a global coalition against corruption — believes in a different approach to retrieve stolen funds.

He says the current process takes long, and that by the time a conviction is secured, the perpetrators have already successfully hidden or transferred the stolen assets.

“The Government should put in place very clear structures on how to recover these assets. In fact, there should be non-conviction-based recovery of assets and infrastructure, whereby — as long as there is some evidence — you don’t need to go through the long court process. Once it is discovered that the funds were illegally acquired, the court should have the power to seize them,” Wandera says.

He says as civil society, they advocate lifting the political veil to eliminate selective prosecution or favouritism based on an individual’s status, if the fight against corruption is to succeed.

Peter Wandera, the executive director of Transparency International Uganda — a global coalition against corruption — believes in a different approach to retrieve stolen funds.

“Once there are political undertones and interference in the fight against corruption — whereby some people seek political protection and patronage — it increases their impunity. The person knows that even if they are caught, they have the political backing and always appeal to political sentiments,” Wandera says.

Jane Nalunga, the executive director of the Southern and East African Trade Information and Negotiations Institute (SEATINI) Uganda, warns that the high prevalence of corruption is escalating the poverty levels.

SEATINI is an organisation that works to promote pro-development trade, fiscal and investment-related policies and processes.

“Corruption increases inequality by making the poor, poorer and the rich, richer, which undermines the possibility of living dignified lives with basic rights like access to education, health and clean water,” Nalunga says.

To bolster the fight against corruption, the Judiciary has adopted modern technologies, including the Electronic Court Case Management Information System, which enables users to file cases from any location.

This system reduces human interaction, thereby minimising opportunities for corrupt practices.

Jane Nalunga, the executive director of the Southern and East African Trade Information and Negotiations Institute (SEATINI) Uganda, warns that the high prevalence of corruption is escalating the poverty levels.

The Judiciary permanent secretary, Pius Bigirimana, says they are working to ensure transparency in the procurement processes.

“For instance, to keep corruption and bribery at bay, the institution has provided a uniform to staff — specifically clerks, process servers, office attendants and drivers — to ease identification and enhance accountability.”

Marlon Agaba, the executive director of the Anti-Corruption Coalition, says holding political leaders accountable is a critical issue that must be addressed in the fight against corruption.

“We have seen corruption being engineered at the highest level of the Government, including Parliament, where people are receiving hundreds of millions to influence some pieces of legislation. So, we have a country that is entrenched from top to down. We need leadership at different levels if we are going to address the issue of corruption,” Agaba says.

He says Uganda should benchmark in countries where leaders have been at the forefront of fighting corruption.

“When you look at countries that have done quite well in terms of addressing corruption, leadership has been committed from day one, from the top to the bottom. Once we have leaders who are committed to fight corruption, that can make a difference,” Agaba says.