Cassettes, Soda and Cedar Trees: Christmas in the 1980s

Christmas Day itself moved slowly. Church bells rang early. Food was served. Soda was opened after church, never before. The day was stretched carefully, as though it could run out if handled carelessly.

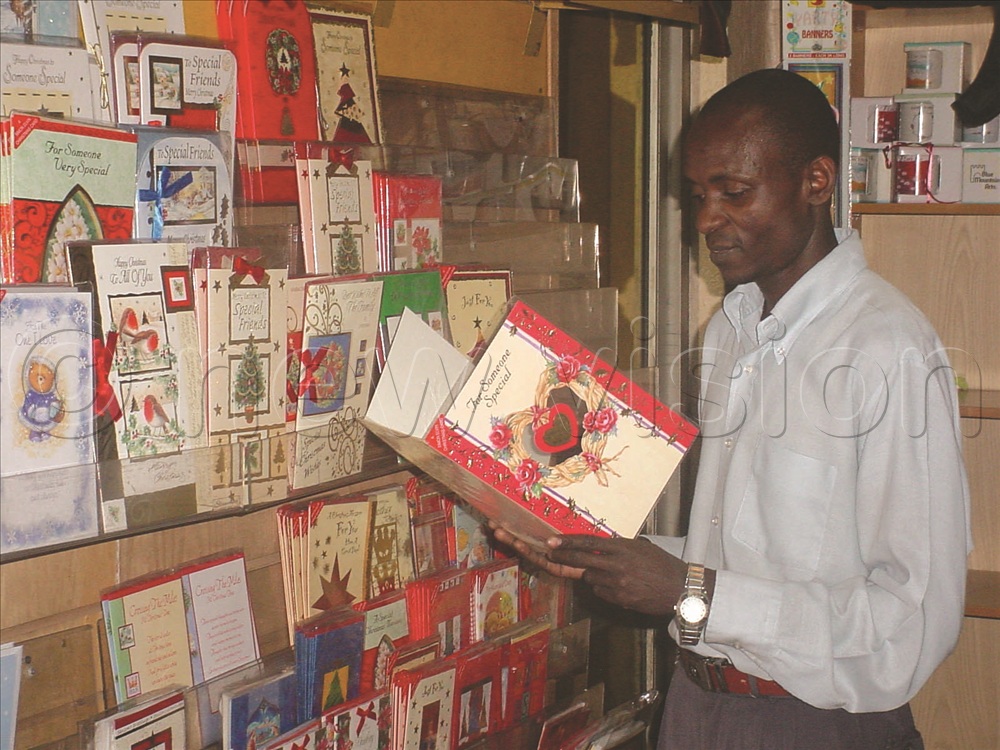

Decorations came from imagination and creativity rather than shops. Cotton pieces sufficed for snow on the cedar tree.(Photo credit: Vision archive )

________________

Except for the early morning bells, Christmas in Uganda in the 1980s arrived quietly, then all at once. It did not announce itself with abundance, but with anticipation for cards, new clothes, cedar trees, chicken and soda.

You heard it first - in the crackle of Segicco and Soul Music cassette tapes, in the rising chatter at bus or taxi parks, in the way neighbours began speaking of “home” with urgency.

On this morning, clothes were worn slowly, food served deliberately, and soda opened only after church, as if the day itself could run out. It was a season made not of plenty, but of effort, invention and togetherness.

Christmas cards

Then, music carried Christmas on its back. The soundtrack was stored on cassette tapes, which were rewound until the ribbon grew thin or cut. Michael Jackson, Lionel Richie, Whitney Houston, Boney M and Kool & the Gang filled sitting rooms and trading centres.

Locally, Jimmy Katumba’s deep baritone held sway, Elly Wamala’s voice commanded silence, and Afrigo Band of course stitched joy into the air wherever a speaker could reach. South African sounds by Brenda Fassie or Chaka Chaka sizzled out of borrowed tapes, competing for attention with Congolese guitar lines and soul classics.

Songs were played again and again, not because choice was limited, but because of their appeal. Young people cleared space in sitting rooms and courtyards, in schools, chairs were pushed aside. Then dust would be seen rising as the running man steps and improvised moves were practised with seriousness.

In Kampala, names like Francis Odida, Mad Mike and Martin Ssempa, before he was elevated to a pastor, travelled ahead of them. These dancers were spoken of the way people spoke of popular footballers like Sekatawa, with admiration, exaggeration and certainty. This replicated in Entebbe, Mbale and Soroti before they became cities.

You guessed right – travel marked the true beginning of Christmas. As December drew near, Uganda Transport Company, Gaso Transport Service and Gateway Bus Company were busiest.

Tickets were bought early or negotiated loudly. Some people travelled with modest luggage - a small suitcase, an improvised tablecloth tied in a Sambusa shape - but it carried large expectations.

Chickens clucked under seats. Children slept on laps. Some journeys led up-country, to ancestral homes and familiar paths. Others led into Kampala City, drawn by electricity, music and the promise that something might happen there.

Christmas treats were rare enough to feel ceremonial. In most homes, Tree Top or Quencher juice and soda appeared only in December. Family and Nice biscuits were hidden until the right moment. Crates of White Cap, Pilsner and Tusker beer, smuggled from Kenya, were sipped slowly and shared deliberately.

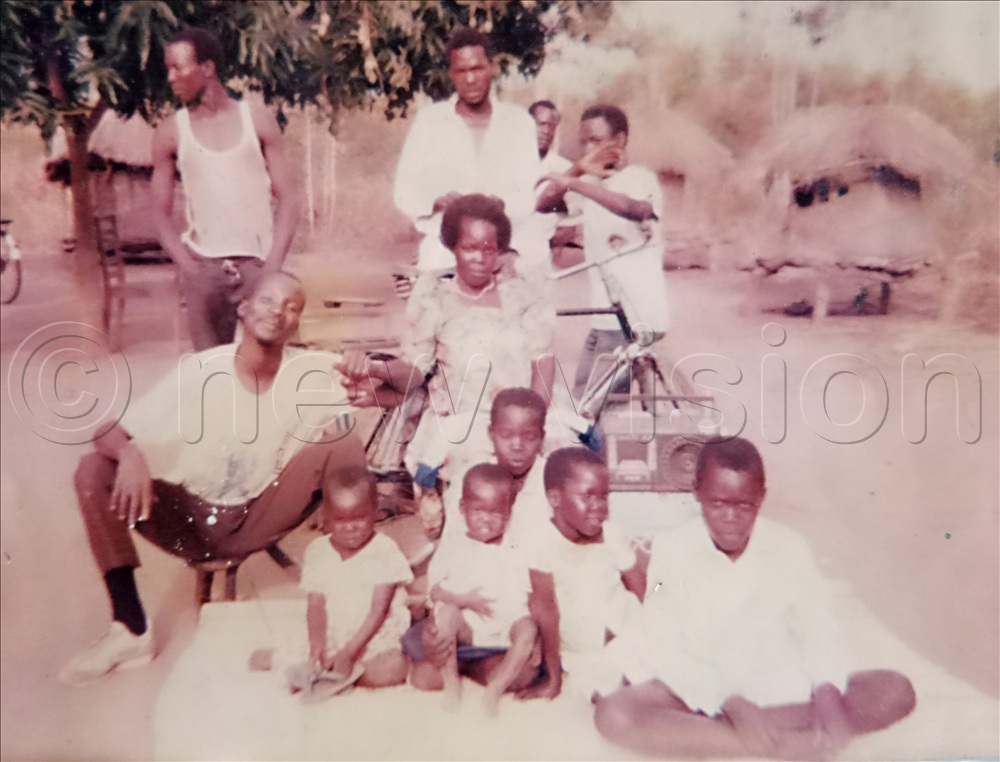

Acaye (seated right) with his parents, brothers and sisters on the Christmas of 1993.

For most, Kasese and Lira Lira gins, sharpened with fresh lime juice, did the magic. Ajon, the frothy millet beer was ready on the day. Beverages were poured sparingly, glasses rinsed between turns, conversation flowing more freely than the alcohol.

Decorations came from imagination and creativity rather than shops. Cotton pieces sufficed for snow on the cedar tree. When tinsel could not be found, toilet paper was cut into strips and pasted across ceilings in long, decorous lines. Sometimes old newspapers joined in, pages folded and hang carefully. The result was uneven, temporary and beautiful. It was understood that Christmas did not need to look perfect - only different from ordinary days.

Reading material mattered. True Love and Drum magazines passed from hand to hand, creased at the corners, quoted confidently in conversation. Owning the latest issue meant visitors lingered longer.

From across the border came The Daily Nation, carrying some stories that did not always find room in Ugandan papers. Wahome Mutahi’s Whispers column was read with relish, sometimes aloud, sometimes in knowing silence.

Radio stitched the country together. UBC (then known as UTV) was solo on air - Habari Gani was a popular Sunday program. Kiswahili speakers leaned toward KBC’s Mambo Tele, adjusting antennas patiently.

Newspapers arrived with New Vision, Weekly Topic, and The Scanner’s column ignited arguments that stretched well beyond the printed page. Discussions spilled into markets, workplaces and family gatherings, continuing long after the paper had been folded and set aside.

What one wore mattered. Walker suits and safari boots announced arrival. Clothes were worn carefully, especially on Christmas Day, when new outfits felt stiff and important.

Gadgets told their own story. Owning a radio cassette player lifted you above the ordinary. Your name travelled. Any party worth attending sought you out, and organisers made sure batteries were bought early, knowing power cuts were almost certain when Owen Falls Dam stood alone as the country’s power source. A Bic pen was not just for writing - it was pushed into cassette wheels to rewind tape by hand, saving batteries for later.

Television ownership placed a household on another level entirely. On Christmas evening, neighbours gathered without formal invitation, chairs dragged in from all directions. Programs were watched communally - The Jeffersons, Mind Your Language, and football highlights from Germany - whenever electricity allowed.

When power failed, people stayed anyway, recounting what they had seen the last time, or arguing about who scored which goal. Movies like Pretty Woman, Bodyguard, Coming to America and Tough Guys were the videos to slot in the player and watch with peers.

Christmas Day itself moved slowly. Church bells rang early. Food was served. Soda was opened after church, never before. The day was stretched carefully, as though it could run out if handled carelessly. There was laughter, there was noise, and there was the quiet satisfaction of having arrived at the day at all.

At the time, we did not think of this as nostalgia. We did not know we were “making memories.” We only knew that the tape must not tangle, the batteries must last, the bus must arrive, and Christmas must somehow carry us to nightfall.