Citizens’ Manifesto: Why most Ugandans worried about quality of healthcare

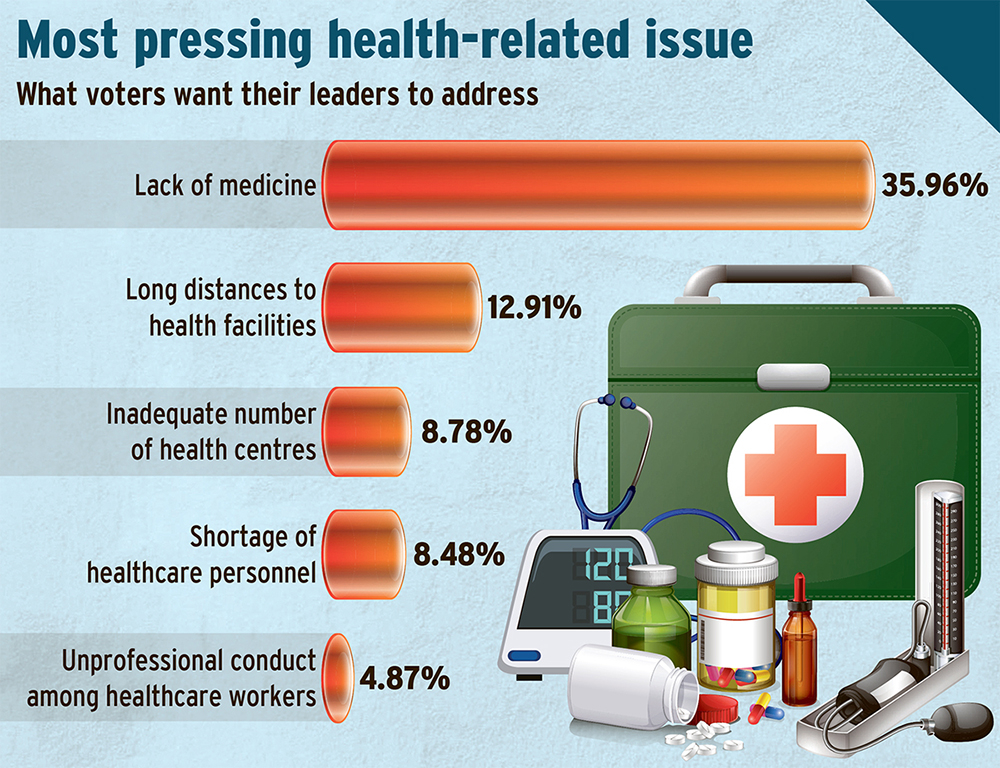

According to the survey, the most pressing health-related issue voters want their leaders to address is the lack of medicine, cited by 35.96% of respondents.

According to the survey, the majority of respondents (40.2%) reported a lack of medicines in health centres.

________________

Seven-year-old Daniel Mbulamuko was rushed to a health centre in eastern Uganda in March this year, with a high fever and convulsions.

He was diagnosed with severe malaria, a common but treatable illness. But the hospital pharmacy was empty.

“They told me to go and buy the drugs from a private pharmacy,” Jane Nairuba, his mother, recalls, sitting outside her one-room house in Budaka district.

“I had only sh5,000 in my purse. The medicine they asked for cost four times that,” she added.

However, by the time Nairuba returned two hours later, having begged relatives for help and walked to a town pharmacy and back, it was too late. Her son had died.

“All they could say was: ‘We’re sorry, the medicine should have been here,’” she says.

Nairuba’s tragic experience is no different from Faith Nagudi’s in January this year. The teacher at Mbale Secondary School was on her way to work when tragedy struck. She had taken a bodaboda, as she often did, when a van — locally known as a drone — rammed into their motorcycle on the Mbale-Tororo road.

Both Nagudi and the bodaboda rider were dragged under the speeding vehicle for a distance before the vehicle stopped. By the time the dust settled, the rider had died while Nagudi was critically injured. She would spend the next six months in the hospital, fighting for her life.

“We have sold everything,” Nagudi said, her voice heavy with emotion at her hospital bed in Mbale.

Her injuries were severe: a broken hip and fractures to her left arm and leg. The family has spent millions in a desperate bid to save her life and restore her health, yet she still needs specialised medical care.

The two experiences mirror findings of a Vision Group opinion poll released in June that shows that the majority of Ugandans (53%) want health services prioritised above all else.

The survey, which was conducted between March and May this year, covering 6,006 Ugandans across 58 districts in 17 sub-regions of Uganda, named other key concerns as education (35%), poverty and roads (29%), employment (19%), water and sanitation (16%), food security (15%), and national security (15%).

Land access and energy concerns were cited by 8% and 13% of the interviewees, respectively, underscoring the need for improved public services and livelihoods. The survey targeted citizens aged 18 and above with a valid national identity card.

Regional variations

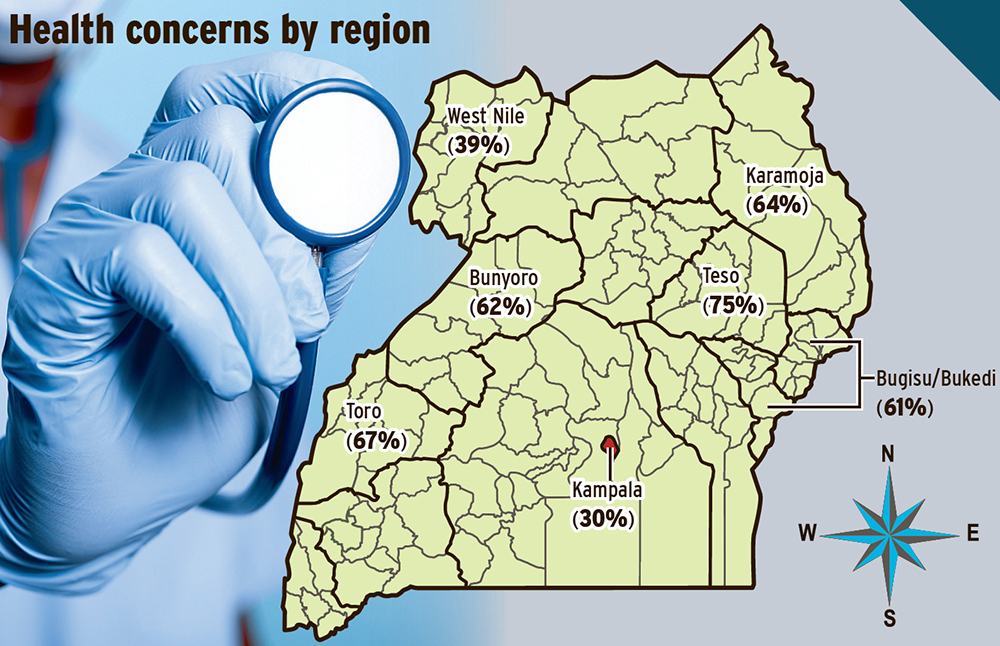

The findings of the survey showed that health, as a key campaign issue, varies significantly by region, with Teso leading at 75%, Toro at 67%, Karamoja at 64%, Bunyoro at 62%, and Bugisu/Bukedi at 61%. But it is of less concern in Kampala (30%) and West Nile (39%).

It also showed that health is a cross-cutting concern directly (in the form of poor health service delivery) and indirectly (through poverty, infrastructure and security issues), highlighting the need for a holistic, multi-sectoral response to improve health systems alongside education, transport, power and social welfare.

Dr Nicholas Thadeus Kamara, the Kabale municipality MP and a member of the parliamentary health committee, said he was not surprised that health features as a top priority ahead of the 2026 general election.

He said while the Government has, over the years, increased the health sector budget, out-of-pocket spending, especially for specialised medical care, still accounted for a large percentage of total health expenditure for many Ugandans, especially vulnerable households, pushing them into poverty due to high medical bills.

“The high cost of accessing medical care is one of the biggest reasons many Ugandans remain poor,” he said.

“Families spend most of their income on health and school fees. If the Government made these more affordable, we could cut poverty by half.”

Kamara, who practised medicine before joining politics, believes improving health care is not just a medical issue, but also an economic one.

“You can’t grow a business or send your children to school if you’re always in and out of hospital,” he said.

Kamara argued that if the Government were to make health care affordable, Uganda could significantly reduce poverty.

“That is why we, in the Parliamentary Health Committee, have been advocating health services to be as accessible and affordable as possible. People have to pay exorbitant amounts to treat diseases like cancer, diabetes and hypertension, which the Government does not adequately subsidise,” he said.

Persisting gaps

Despite the progress, Kamara warns that more work is needed to address gaps that remain, particularly in staffing, medicine availability and medical technology.

“You can build a health centre, but a facility is more than buildings,” Kamara said. “Are the workers present? Do they have drugs? Are they using modern tools to diagnose and treat?”

He commended the Government for recent efforts, including salary increases for doctors and nurses, but stressed that foundational issues, such as human resource shortages and governance, need urgent attention.

“Yes, salaries have gone up, but has patient care improved? Are health workers attending to patients as they should?” he asked.

Kamara also called for stronger government action on noncommunicable diseases, which are responsible for 33% of the deaths in Uganda.

“Over 80% of patients at the Uganda Cancer Institute arrive at stage three or four, too late for curative treatment,” he said.

Kamara stressed the need for early detection, improved primary health care and a level of political commitment similar to that which was given to HIV/AIDS and malaria.

Govt promise

In 2021, the Government pledged in its manifesto to prioritise efficiency and effectiveness in the delivery of health services.

The focus was to continue addressing key pressing needs in the sector, particularly the availability of essential drugs.

This was to be achieved through the promotion and development of the pharmaceutical industry, including interventions such as providing incentives to support the local manufacturing of drugs and medicines.

The Government also committed to supporting research by scientists to identify new drugs and promote capitalisation through global patenting.

Additionally, it aimed to enhance research and development in indigenous medicine at key research institutions, to enable traditional healers to upgrade their products and develop appropriate and resilient drugs.

According to the Ministerial Policy Statement for the Financial Year 2025/2026, improving the functionality of the health system to deliver quality and affordable preventive, promotive, curative, and palliative healthcare services remains one of the Government’s top priorities.

However, the Vision Group survey found that inadequate equipment in health centres – including a shortage of intensive care unit beds and ambulances – remains a significant challenge.

According to the survey, the most pressing health-related issue voters want their leaders to address is the lack of medicine, cited by 35.96% of respondents.

This was followed by long distances to health facilities (12.91%) and the inadequate number of health centres (8.78%).

Other concerns raised include a shortage of healthcare personnel (8.48%) and unprofessional conduct among healthcare workers (4.87%).

Joel Ssebikaali, the deputy chairperson of Parliament’s health committee, said a key missing link is the lack of a national health insurance scheme.

“Right now, 41% of Ugandans pay for healthcare out of pocket. That’s why so many fall into poverty when they get sick,” he said while speaking during a recent high-level stakeholders meeting at Protea Hotel in Kampala.

He said the out-of-pocket spending was driving people into the hands of unqualified traditional healers.

Ssebikaali blamed powerful government insiders for misinforming President Yoweri Museveni, leading to the nonassent of the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) Bill, which Parliament passed in 2021.

Bill revisions underway

Sheema Woman MP Rosemary Nyakikongoro said the NHIS Bill was withdrawn after stakeholder consultations exposed critical gaps.

“Some people feared it would overburden the already struggling families, especially those detained in hospitals for unpaid bills,” she said.

Nyakikongoro added that Parliament is working to rebuild momentum behind the Bill through advocacy and inclusive stakeholder engagement.

“We also need to include those in the subsistence sector.

These are the people who are struggling the most with access to medical care,” she said.

Prof. Francis Omaswa, the executive director of the African Centre for Global Health and Social Transformation, said implementing the NHIS would have long-term economic benefits.

“For example, in Germany, the health sector contributes up to 30% of GDP. The COVID-19 pandemic showed the world that without a strong health system, you can’t have sustainable economic growth,” he said.

Omaswa urged policymakers to move forward with the Bill and design a model that builds confidence among political leaders.

Crucial issues

According to the survey, the majority of respondents (40.2%) reported a lack of medicines in health centres, followed by inadequate health facilities and services (20.6%), and long distances to health centres (14.3%).

Additionally, inefficient service delivery – including staff misconduct, delays, and expired drugs – affects 13.1% of respondents, while a shortage of healthcare workers and the high treatment costs accounted for 7.6% and 3.8% of the responses.

Other critical but less cited issues included the rising disease cases, poor sanitation, overcrowded institutions, and corruption that accounted for under one per cent of the responses, according to the survey. This underscores the need for a holistic, multi-sectoral response.

Residents call for action

Residents of Fort Portal city said hospitals regularly struggle with long patient queues, frequent drug stockouts, and understaffing.

“When I went to Buhinga Hospital, I was told to buy the medicine from Kampala, but the patient died before the drug could reach,” Haruna Kibirango, the Rwengoma A1 resident, said.

Kibirango also says the health facilities in the city are overstretched. Some wards function with just five beds and emergency patients are sometimes treated in tents.

“The ICU capacity is severely constrained, with only four beds available in a high-need region,” he said.

Rev. Kintu Willy Muhanga said the number of health workers at some of the health facilities in Fort Portal is small, compared to the number of people they receive.

“I had a challenge with my tooth, and when I went to Buhinga, I found about 50 people in the queue to see the dentist,” he said.

Muhanga challenges the Government to step in and recruit more health workers, especially in facilities like a regional referral, to prevent burnout.

Sarah Kebirungi, 27, a resident of Kasusu, says much as she received the service at Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital when she gave birth, she bought everything herself.

“It is clear that while health facilities exist, consistent and complete service delivery remains a challenge. Often, patients leave without receiving the full treatment they came for.

In many cases, one is either partially attended to or not helped at all,” said Clare Nayebare, a resident of Kasusu ward.

Nayebare said when tests are done, the health workers prescribe medicines that are too costly for the average person to afford in private pharmacies.

She added that in situations where medication is dispensed, it is frequently limited to basic painkillers like paracetamol.

She, however, admits that the healthcare workers who serve in these public facilities, in most cases, are doing their best under difficult circumstances and believes the root of the problem lies in systemic shortages of medicines, resources, and consistent supply chains.

Lango sub-region

Richard Agem, the assistant district health officer of Alebtong district, said by standard, the district was supposed to have 206 nurses and 113 critical midwives in the health facilities, but there are severe imbalances, which need urgent attention.

He said the challenge of inadequate human resources is affecting the quality of health care provision, posing a heavy workload and affecting the personnel psychologically.

Bunyoro

Voters in Hoima district have asked politicians vying for different political positions to address the challenges of understaffing in health facilities so as to improve service delivery to the communities.

Several sub-counties in the district do not have a health centre III, even when it is the government’s policy to establish a health centre in every sub-county.

Justine Kemigisha, a patient at Kigorobya Health IV in Hoima district, disclosed that some patients are sent home too soon due to a shortage of health workers.

Kemigisha said the alarming shortage of health workers at the facility has threatened the lives of the patients.

Another patient, Brian Otyeno, disclosed that some patients are sent home without adequate education about how to take care of their illness due to a shortage of health workers.

The 2024 national census indicates that the population stands at about 374,500, but that the district has only one health centre IV.

The lack of an anaesthetist at Kigorobya Health Centre IV in Kigorobya county, Hoima district, is also affecting service delivery.

Dr Lawrence Baluku, the officer in charge of the facility, said recently that the facility is faced with a challenge of shortage of staff in the theatre and appealed to the district leaders to recruit more staff.

Dr Diana Atwine, the permanent secretary in the Ministry of Health, asked the Hoima district leadership to ensure that they urgently recruit critical staff.

During the recent Bunyoro Regional Stakeholders Annual Health Review engagement held in Hoima, which attracted both political and technical leaders from across the districts that make up Bunyoro, participants expressed concern over the rising rate of maternal deaths.

At Hoima Regional Referral Hospital, 83 mothers died in the financial year 2023/2024 while giving birth. Most of the women who died were as a result of referrals from other lower health facilities in the sub-region.

Evelyn Achayo, the senior principal nursing officer at Hoima Regional Referral Hospital, highlighted several key causes of maternal deaths, including delayed referrals, absenteeism of competent health staff, and inadequate transportation.

She also revealed the vice of unqualified staff attending to expectant mothers due to a shortage of trained personnel across most health facilities in the region.

“Maternal death is a critical issue that we need to address urgently as a region because we are losing many mothers. The leading factor is late referrals, especially from long distances, such as Kyangwali, Buliisa, Kagadi, and Kakumiro, which are all over 100km away. Late referrals can be dangerous,” Achayo said.

According to the leaders, even districts that have ambulances often face fuel shortages, a situation that has tragically led to the deaths of many mothers during childbirth.

Irene Akanwansa, a medical worker at Kyangwali health centre IV in Kikuube district, said in most cases, whenever they receive women with birth complications, referring them to Hoima becomes tricky because they lack transport.

“We refer all the complicated cases to Hoima, but sometimes women spend three days without reaching the hospital because of transport challenges. We sometimes rely on cars from the refugee camp for free transport,” she said.

The highest percentage of maternal deaths due to delayed referrals was recorded in Kikuube at 32%, followed by Hoima district at 11%, and Kyankwanzi at 9%.

Medics at Hoima Regional Referral Hospital have been urging lower health facilities to make timely referrals and also call for additional staff, especially midwives and doctors, to handle the increasing number of patients seeking specialised treatment at the hospital.

Govt interventions

In a bid to improve access to health services and accelerate progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the Government has rolled out several healthcare interventions over the past few years.

In April, Prime Minister Robinah Nabbanja commissioned 398 health centres III and three new regional blood banks. According to the health ministry, Uganda now has 1,696 functional health centres III out of the 2,184 sub-counties nationwide, covering 78% of the country’s administrative units.

This achievement is part of a wider effort stemming from a 2018/2019 Cabinet resolution that prioritised maternal and child health, calling for the upgrade of second- and third-tier health centres and the construction of new facilities where they were lacking.

“These facilities represent a transformative leap in our healthcare system, bringing quality and accessible care closer to our communities,” Nabbanja said.

Health minister Dr Jane Ruth Aceng echoed the Prime Minister’s remarks, noting that the country had made significant gains in maternal and child health outcomes. These improvements are supported by increased government spending.

In the 2025/2026 financial year, the health sector was allocated sh5.86 trillion. This is nearly double the sh2.95 trillion budgeted for in 2024/2025.

The increased funding reflects a renewed focus on strengthening public health systems amid growing health burdens, diminishing donor support, and increasingly stringent donor conditions. The Government has also expanded its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) monitoring framework, increasing the number of indicators with available data from 45 in 2016 to 134 in 2024.

Linda Asaba, the head of programmes at the United Nations Association of Uganda, which is working with the Government on monitoring of the implementation of SDGs, said Uganda has made measurable progress toward the attainment of SDG 3. It focuses on ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all people.

“There has been a reduction in maternal mortality, which dropped from 336 deaths per 100,000 births in 2016 to 99 per 100,000 in 2020,” she said.

She added that the number of new HIV infections declined to 53,000 in 2019 and that access to affordable medicine and health supplies increased from 11.5% in 2016 to 35.8% in 2020.

She added that it is no surprise that Uganda’s ranking on the United Nations Human Development Index has risen in recent years and catapulted the country from low human development countries to the medium human development category.

Regional differences

The survey revealed striking regional variations. In the Teso region, for example, 75% of respondents cited health as a top concern, followed by Toro (67%), Karamoja (64%), Bunyoro (62%), and Bugisu/Bukedi (61%). In contrast, West Nile (39%) and Kampala (30%) reported relatively lower levels of concern.

Concerns, way forward

Evaline Birungi, a health assistant at Nangoma Health Centre II in Kyotera, emphasised the urgent need for more drug supplies and personnel to address the challenges caused by inadequate staffing.

“We have 11 staff instead of the required 22,” she said. “We’re overstretched, especially during malaria season.”

She added that some communities, including those living near landing sites such as Kasensero on Lake Victoria, struggle with frequent outbreaks of typhoid due to unsafe water, particularly at the onset of the rainy season in April.

This concern was echoed by Ronah Wamwangu, a former nurse and midwife from Mbale Regional Hospital in Mbale district.

She pointed to long queues at government health centres as a major issue, highlighting the urgent need to recruit more health workers. She noted that, as a result, some patients resort to seeking care in poorly equipped private facilities within their communities.

“We are seeing many mushrooming drug shops; unfortunately, many people believe these facilities can solve all their health problems.

This is risky, especially for expectant mothers, because many of these facilities lack the capacity for proper checkups,” she said. She recounted a recent case in which an expectant mother nearly died from severe malaria.

Wamwangu urged the government to invest more in health sensitisation campaigns, particularly through mass media such as radio, which is widely accessible in her community.

Medical association speaks out

Uganda Medical Association secretary general Dr Herbert Luswata said there is a need for the government to reorganise its priorities.

“You can delay the construction of a road, but not provision of treatment,” he said, calling for efforts to result in regular replenishment of essential tools and specialists in regional referral hospitals through increased funding for National Medical Stores and a wage provision to implement the new public service structure.

“Even with political will, no hiring can happen without money. The president directed that every health centre III should have at least two medical officers to reduce maternal deaths.

“But that hasn’t happened because the Public Service ministry says there’s no wage provision,” he said.

Luswata said Uganda has the potential to treat all its citizens, including important persons, such as government officials.

“We need to increase the overall health budget and also discourage medical tourism for big people in the Government.

“We can use part of that money to recruit specialists and help us increase specialised care in those hospitals. When you look at Mulago National Referral Hospital, it receives less than 60% of its budget, and they say there is no money, yet a lot is wasted in medical tourism,” he said.

Multi-sectoral response

Dr Charles Olaro, the director of general of medical services at the health ministry, welcomed the Vision Group survey, saying an analysis will be made to address the gaps. However, he offered context to challenges such as Nairuba’s predicament. Olaro said Uganda’s healthcare system is structured hierarchically, starting from the grassroots level.

Structure: At the base of the health system are the village health teams (VHTs), followed by health centres II at the parish level, health centres III at the sub-county level, and health centres IV at the county level. Above these are district hospitals, regional referral hospitals, and finally, national referral hospitals.

“One must move up this structure; the level of care becomes more advanced, with higher-level facilities equipped to handle more specialised and complex medical cases,” he said.

Drug stock: Dr Olaro said shortages may be linked to the timing within the delivery cycle.

Preventive health: Maintain good hygiene, eat right, do routine checks and exercise to reduce visits to hospitals for expensive treatment.

Corruption: The survey shows that only 1% of the respondents cited corruption among health workers as a concern. Dr Olaro noted that digitisation across referral hospitals and health centres IV has reduced drug thefts and improved accountability.

Voters’ voices

Kassim Ratibu Obiti (resident of Kulikulinga North cell in Kulikulinga town council, Yumbe district): Almost every subcounty now has a health centre. This reduces the distance people have to travel to access medical services. However, there are persistent drug shortages in government-run health centres.

Francis Otim (from Hoima): Many sub-counties do not have health centres III, and, as a result, people have to walk long distances to access services. Some women deliver from their homes because they cannot access health facilities. The government should ensure that each subcounty has a health centre III to ease access to services.

Jovia Nakate (from Hoima district): The Government should hire more health workers because many facilities do not have staff, and patients do not get adequate services. Some health facilities also do not have equipment.

Kubura Aliru (resident of Bijo subcounty in Yumbe district): I thank the Government for establishing health facilities in almost every sub-county and upgrading many health centres II to health centre III status. The challenge is the commercialisation of the services in the health centres.

In most of the health facilities, patients purchase drugs and other essential commodities from private facilities. Patients also have to pay for other expensive services such as CT scans, X-rays and oxygen.

Minima Kasifa (resident of Maru East village in Goboro parish, Kochi subcounty in Yumbe district): There are no drugs in most of the health facilities in the area. Most of the time, we are given painkillers, especially paracetamol and are directed to purchase other prescribed medications from private clinics and drug shops. The drug shops are owned by some of the health workers employed in government facilities.

Patra Kebisembo (from Katumba, Fort Portal): The facilities have enough equipment to use, but lack the specialists (radiologists) to clearly interpret the results, especially those from CT scans.

Additional reporting by Adam Gule, Wilson Asiimwe, Jonan Tusingwire and Patrick Okino