Museveni’s political wisdom broadens NRM, strengthens power, weakens opposition

This was not mere rhetoric or showmanship. It was the enactment of what I call the Museveni NRM reconciliation leadership strategy — a deliberate, symbolic display of forgiveness as a mechanism of absorbing dissent, and projecting the ideological frame of inclusion and unity.

Museveni’s political wisdom broadens NRM, strengthens power, weakens opposition

____________________

OPINION

By Boaz Byayesu – Virginia, USA

A symbolic reconciliation at Kololo

On October 9, 2025, Uganda celebrated its 63rd Independence Day under a charged atmosphere of political tension and opportunity. Yet, amid the customary parades, the pomp, speeches, and ceremony at the Kololo Ceremonial Grounds, one moment stood out: the public re-entry of Col. Samson Mande, a former freedom fighter and critic, being officially welcomed back into the NRM fold by President Yoweri Museveni.

In his Independence Day address, Museveni did not mince words:

“I need to salute the peace-loving Ugandans and the UPDF for ensuring peace in Uganda. All that is happening is, first and foremost, on account of the peace that is available. This peace is lubricated by the long-standing NRM policy of reconciliation and forgiveness, on top of our firm stand against crime.” (Source: New Vision, Oct 9, 2025)

He continued:

“Even today, I am happy to welcome back into peaceful Uganda, Col Samson Mande, who had fled into exile on account of, apparently, some internal intrigue. While in exile, he tried to engage in some rebel activities. When, however, our cadres contacted him in Sweden, he happily agreed to come back and disconnect himself from the rebel activities.” (Source: New Vision, Oct. 9, 2025).

This was not mere rhetoric or showmanship. It was the enactment of what I call the Museveni NRM reconciliation leadership strategy — a deliberate, symbolic display of forgiveness as a mechanism of absorbing dissent, and projecting the ideological frame of inclusion and unity.

The strategy of reconciliation as a political genius for continuity and stability

Too often in African politics, forgiveness is framed as weakness. But in Uganda under Museveni, reconciliation has been wielded as a political weapon. It is a mechanism for turning former adversaries into allies, reabsorbing potential threats, and saturating the political theatre with narratives of unity.

This is not simply strategic leverage; it is moral high ground. A reconciled critic carries within them a story of redemption. They become living testimony to President Museveni’s mercy, clemency, and continued leadership of purpose and vision. When opposition figures are pardoned and reintegrated, the message is: the system is magnanimous, and resistance is less potent if it can eventually be embraced.

This is not theoretical. We can trace this trajectory in several high-profile cases:

From death row to adviser — The Rwakasisi redemption

Few stories better illustrate this dynamic than the case of Chris Rwakasisi, a former Obote-era Security Minister whose fall and resurrection mirror Uganda’s own political contortions.

Rwakasisi was convicted of serious crimes—including armed kidnapping and murder— following the overthrow of Obote’s regime and was sentenced to death. He spent 24 years on death row in Luzira Maximum Security Prison, enduring extreme isolation, trauma, and uncertainty over his fate

His life changed drastically in 2009 when Museveni, after what he described as a spiritual reflection, granted him an unconditional pardon. Over time, Rwakasisi reframed his narrative: he moved from being Museveni’s bitter enemy to a public admirer. He has since described

Museveni as “my greatest friend in Uganda”

Today, Rwakasisi serves as a Presidential Advisor for Special Duties, frequently speaking of forgiveness, reconciliation, and the moral lessons of the right leadership. His very presence is a walking testament to the redeeming power of mercy and empathy.

High-Profile reconciliations strengthening the NRM:

Aggrey Awori – Once a senior figure in the opposition and Minister under various regimes, Awori publicly embraced NRM policies in the 2000s, citing national stability and Uganda’s need for unity over partisan rivalry (Source: New Vision, 2010). His alignment showcased how ideological adversaries could be drawn into the reconciliatory fold without diminishing their legacy.

Moses Ali – Former Vice President under a coalition government, Ali had political disputes with the NRM in the 1990s and early 2000s. His eventual reconciliation, formalised through party consultations and public acknowledgement, reinforced NRM’s narrative that inclusion is stronger than exclusion (Source: Daily Monitor, 2015).

Taban Amin – The son of former President Idi Amin, Taban Amin’s return to Uganda’s political mainstream and engagement with Museveni’s government signalled that even politically sensitive figures could be reintegrated under the NRM umbrella. This move strengthened the perception of NRM as a vehicle for national healing (Source: New Vision, 2018).

Norbert Mao – A prominent opposition leader and former President of the Democratic Party, Mao has publicly recognised opportunities for dialogue and collaboration with the NRM on key national issues, exemplifying how reconciliation can extend across party lines without formal party membership.

By converting an old enemy into a public symbol of reconciliation, the NRM party accomplishes multiple objectives:

- It neutralises any lingering claim to moral high ground by the

- It reinforces the narrative that the African strongman-style vendettas are not Uganda’s

- It gives Museveni the optics of faith, mercy, clemency and divine.

Reabsorbing rebels — The case of Samson Mande

Samson Mande, a veteran of the liberation struggles, later fell out with the NRM leadership, fled into exile, and was accused of aligning with rebel elements abroad. (Source: Daily Monitor, “I’m back to my home NRM,” Oct 2025)

His return during the Independence Day events was presented with full symbolism: at Kololo, Museveni publicly welcomed him.

Mande’s reintegration sends a powerful signal: dissent may be tolerated, disloyalty forgiven, and former conflict transformed into legitimacy. His re-entry underscores the central thesis of the Museveni—NRM reconciliation power strategy — that mercy can serve as ironclad control.

Mande himself, upon addressing the crowd, said:

“I am back home … My second home is the NRM. NRM was born by us. It is in me; it will remain in me until death puts us asunder.” (Source: Daily Monitor, Oct 2025)

Such statements recast ideological opposition into emotional personal belonging — effectively shifting the frame from confrontation to communion.

The Weapon of Inclusion

The strategy of inclusion operates on the principle that national unity is fundamental to security and progress. By excluding opponents, a government merely validates their resistance. Forgiveness, however, dismantles this opposition, effectively suspending hostilities and co-opting the former outsider into the system.

Across African political history, we see two approaches:

- Exclusion and purging of dissenters, which may consolidate power in the short term but breeds underground rebellion, fragmentation, and cycles of.

- Inclusion, reconciliation, and co-option, which convert adversaries into partners, defuse polarisation, and anchor.

- In Museveni’s Uganda, reconciliation is not just a moral. It is part of the

- reconciliatory winning strategy — a long-term tool to absorb opposition, reshape narratives, and dominate the political narrative of unity over.

Forgiveness as a leadership asset — Lessons from Nyerere

The concept that a leader's strength lies in the capacity to forgive is not unique to Uganda. Indeed, as Julius Nyerere, the founding father of Tanzania, actively focused his ideology on fostering national unity, Yoweri Museveni, too, who is Nyerere’s good friend and a good student of politics, understood his ideology and methods of work. Nyerere championed the belief that the politics of unity must always eclipse the destructive forces of patronage or exclusion.

Today, Museveni resonates in this philosophical font. He often frames Uganda’s success not through his singular strength but through inclusion, extending olive branches, and absorbing past enemies.

Indeed, across the continent, stability often follows those who can convert wrath into reconciliation. In post-conflict Rwanda, Sudan, Sierra Leone, and Mozambique, truth and reconciliation mechanisms have shown that forgiveness can be structured, and when properly legislated, it can underpin peaceful transitions.

2026: The politics of reconciliation

As Uganda approaches its hotly contested 2026 elections, the Museveni NRM reconciliation power strategy is not just symbolism — it is strategic scaffolding. It does several critical jobs:

- Neutralising opposition. If your fiercest critics are pardoned and publicly praising you, the moral leverage of opposition shrinks.

- Expanding your Every returning dissident brings along sympathisers who may now see NRM as a safe home rather than a persecutor.

- Projecting national In polarised politics, the image of reconciliation rallies moderates and suppresses extremist discourses.

- International Reconciliation bolsters Uganda’s image abroad — as not merely authoritarian, but as a state that tolerates dissent and practices mercy.

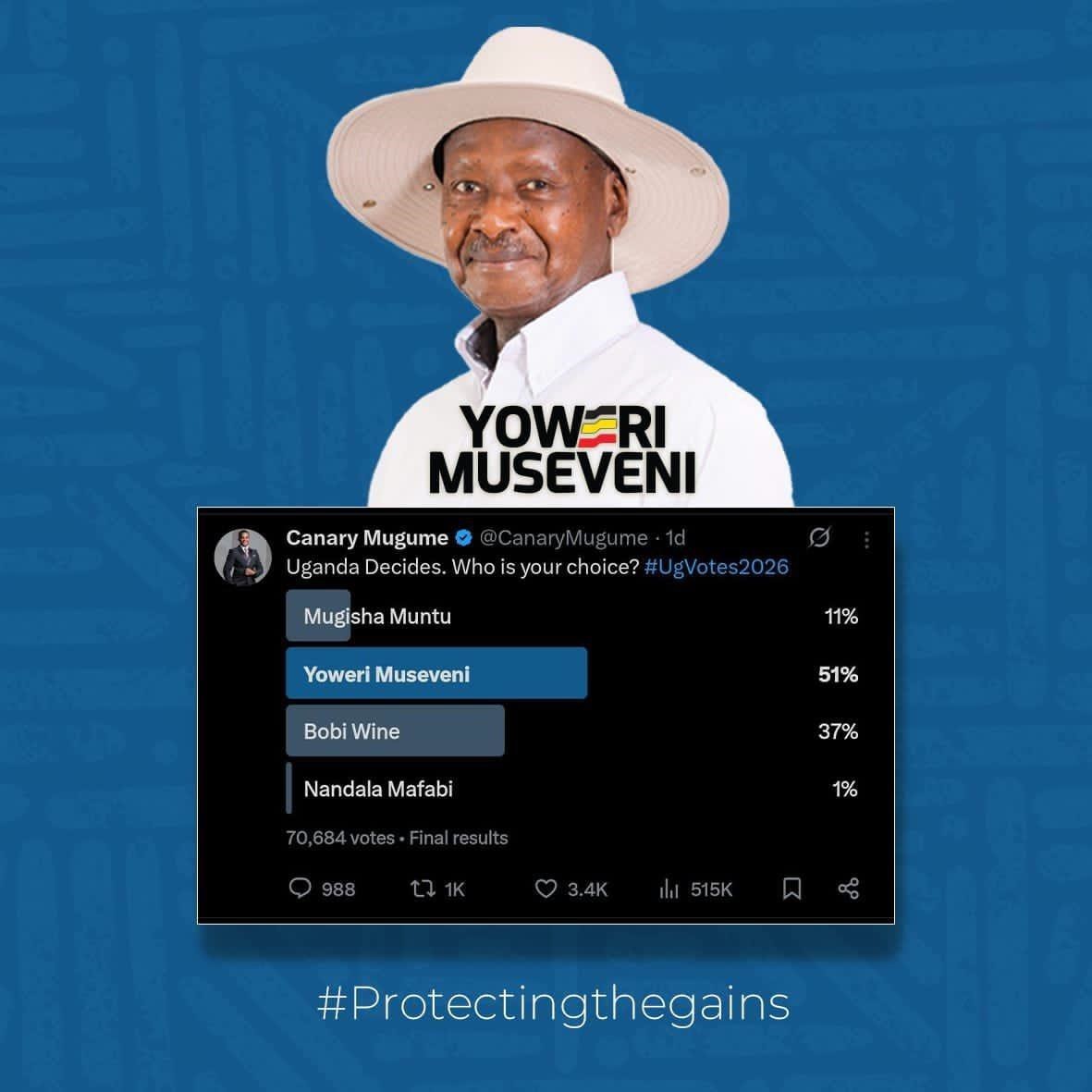

Consider data from recent polls. In the Canary Mugume X Poll, Museveni reportedly led 51% among elite respondents when asked who they would vote for — signaling a shift in the high-end electorate toward him. Reconciliation, inclusion, stability and undertones of Uganda’s growth and development might be core drivers of that shift.

The Power of Mercy

Museveni’s political mastery lies in his ability to convert conflict into compromise, opposition into legitimacy, and enemies into voices of his own moral capital.

As we press toward 2026, the Museveni NRM reconciliation power strategy will be one of his most formidable assets. It is not sentimental; it is deliberate. It is not weakness; it is a form of strength suited for a fragmented, youth-driven, emotionally volatile electorate.

Let us remember: “A leader’s place is wherever the need is greatest.” When reconciliation is needed the most, in communities fractured by history, in identities torn by politics, and in future generations anxious for unity, that is where a leader must stand firm, daring in forgiveness, steadfast in inclusion, and unassailable in dignity.

The writer is from Virginia, USA.