Forgotten Buganda Crown: Legacy of exile and poverty for Buganda’s Kalema lineage

Historical accounts indicate that Kabaka Kalema, a Muslim, was ousted from power through a conspiracy between British colonial agents and Baganda Christian converts. After being exiled to Kijungute in present-day Kiboga District, he was followed and killed, dying what his descendants revere as a martyr’s death.

Forgotten Buganda Crown: Legacy of exile and poverty for Buganda’s Kalema lineage

_______________

OPINION

By Immam Shaffi Kagiiko

Addressing a historical injustice in the Buganda Kingdom: A call for justice for Buganda’s forgotten royals

MENDE KALEMA, WAKISO DISTRICT – The colonial wound is still open. Tucked away in the quiet village of Mende, a stone's throw from the bustling capital, lies a story of royalty, faith and a century-long legacy of neglect. Here, the descendants of King Nooh Rashid Kalema, a 19th-century Kabaka of Buganda, live in a state of profound poverty, a stark contrast to the opulence associated with the kingdom’s throne, and a direct consequence of a colonial-era injustice that remains unredressed.

The story of the Kalema lineage is more than a family matter; it is a test of the kingdom’s integrity and a nation’s willingness to heal the wounds of its colonial past.

The plight of the Kalema lineage is a forgotten chapter in Buganda’s rich history. Their impoverishment is not a tale of mere misfortune but is deeply rooted in the political and religious machinations of the 1880s. Historical accounts indicate that Kabaka Kalema, a Muslim, was ousted from power through a conspiracy between British colonial agents and Baganda Christian converts. After being exiled to Kijungute in present-day Kiboga District, he was followed and killed, dying what his descendants revere as a martyr’s death.

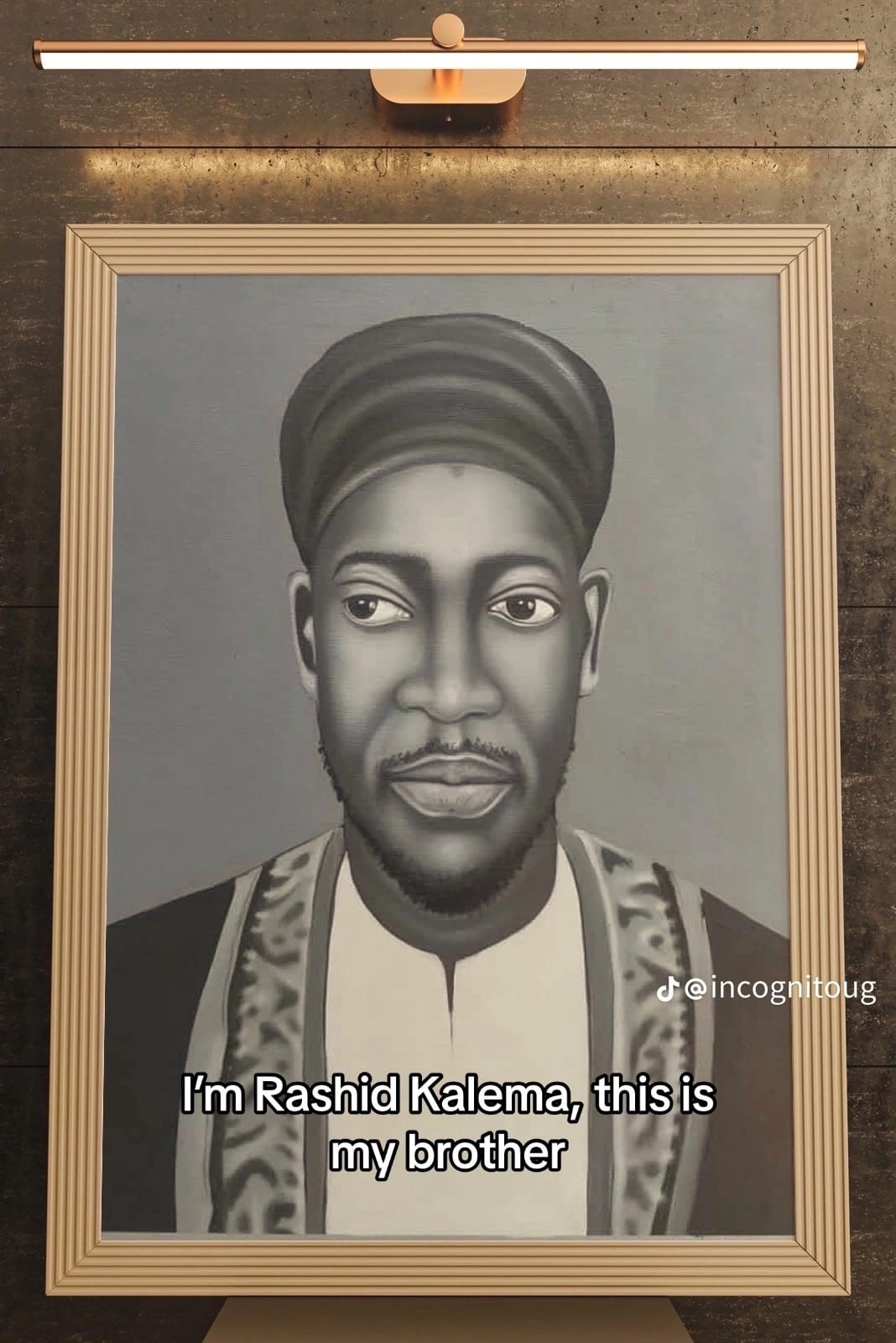

Rashid Kalema.

In fact, Kabaka Kalema should be declared the “Arch Martyr” in the history and commemoration of Martyrdom in Uganda, for he was no ordinary person to have died a staunch Muslim faithful, yet he was a King of a great nation.

The persecution did not end with his death. His family and loyalists were subjected to systematic harassment, forced conscription and intense pressure to abandon their faith. An appeasement strategy followed Uganda’s colonial background, where some family members were offered scholarships or local government positions as county and sub-county Chiefs - but only on the condition they converted to Christianity.

This coercive assimilation created a confused identity that echoes through generations. Descendants were forced to bear hybrid names—Edmond Alamanzani Ndawula, Joseph Yusufu Musanje, Mary Safiya Kamuwanda – all symbolizing a fractured heritage caught between enforced Christianity and a proud Islamic past (according to Sir Apollo Kaggwa in book “Ba Ssekabaka b’eBuganda”). This erosion of identity is embodied by His Royal Highness Edward Kimera, father of Prince Kalema Ibrahim Kimera, a true culmination of the Buganda royals in Kalema’s lineage.

HRH Edward Kimera permitted his Son Ibrahim, out of all his Children, to become a Muslim as a way to reclaim and sustain their grandparents’ Islamic legacy. He lives in the very village named after his royal ancestor, thus MENDE-KALEMA, in Wakiso District.

While the ostensible royal cousins at the Mengo and Kibuli palaces enjoy considerable luxury and influence, the true descendants of Kalema dwell in obscurity and want. Compounding their economic hardship is an alleged orchestrated campaign to dispossess them of the small customary plots of land they still hold. Residents report that influential police officers have even interrupted their public events and prayers, a move seen as an extension of the historical persecution, if not breaching constitutional worship and other freedoms.

There is a growing appeal from historians and cultural observers for both the Central Government of Uganda and the Buganda Kingdom to confront this historical wrong. The colossal wealth and cultural capital administered from Mengo would be moral, not diminished, by a deliberate humanitarian policy to uplift the legacy house of Kabaka Kalema.

To the Right Honourable Katikkiro of Buganda, while the Kingdom rightly celebrates its rich history, the continued neglect of Kabaka Kalema’s descendants, who live in impoverished conditions, represents an injustice; we challenge you to use your office to formally recognize their legacy and initiate a program of restitution to finally heal this deep wound in the Buganda narrative.

Furthermore, international cultural bodies like UNESCO are being called upon to help preserve this critical, yet vanishing, embodiment of East Africa’s history. The story of the Kalema lineage is more than a family matter; it is a test of the kingdom’s integrity and a nation’s willingness to heal the wounds of its colonial past.

More interestingly, it was from the Buganda Kingdom where a woman named Queen Gwolyokka, commonly known as “Muganzilwazza,” having been banished and exiled to Zanzibar by her King, Kabaka Suunna, later remarried to then Sultan Sa’id bin Sultan, thus becoming the first woman to marry two simultaneous reigning kings.

Muganzilwazza left for Zanzibar after mothering Prince Mutesa I, who later became a Kabaka after the death of his father, Suunna. During the reign of Kabaka Mutesa I, his biological brother Sai’d Rashid Bargash, born to the Sultan of Zanzibar by Muganzilwazza, also became the Sultan after his father’s demise.

Thus, it was Mutesa I, who fathered Kalema as one of his sons. The other ones were Mwanga II and Kiweewa Mutebi, who became Kings in Buganda too, as the epochs of succession struggles unveiled.

Today the legacy of King Kalema is patronised by a fourth-generation descendant - Prince Kalema Ibrahim Kimera – reportedly with lots of tales to tell about the plight of this critical historical enclave and journey that shaped the foundations of the state formation process of what became the British Protectorate – Uganda - as declared by the colonialists in 1894.

Not so old in appearance but very bright in mind, Prince Kalema, a Muslim with a perfect resemblance to Kabaka Mutesa I by his facial expression, behaves and speaks like a proud total Muganda Royal, sometimes sounding poetic, understandable, but not so ordinary. He is a typical product of Buganda Kingdom’s royalty and the Kalema legacy in particular.

As one elder in Mende whispered, “We are not asking for a throne, only for recognition and justice. For our children to know that their great ancestor was a king, and that his blood deserves respect, not poverty.” The annals of history will judge how the present generation answers this call.

The writer is a lecturer and national Secretary for Grants and Social Services, Uganda Muslim Supreme Council.