Rubaire farms his way to fame

With sh700,000, they purchased 200 layer birds; the remaining sh300,000 went into feed and constructing a basic shelter on a 35 x 100-foot plot.

Rubaire’s farm produces 90–100 trays of eggs daily. (Photos by Umar Nsubuga)

________________

For the tenth year running, Vision Group, together with the Embassy of the Netherlands, KLM Airlines, dfcu Bank and Koudijs Animal Nutrition, is running the Best Farmers competition.

The 2025 competition runs from April to November, with the awards in December. Every week, Vision Group platforms will publish profiles of the farmers. Winners will walk away with sh150m and a fully paid-for trip to the Netherlands.

In the heart of Kabarole district, Paul Rubaire’s farm is more than just a business — it is a blueprint for rural agribusiness success.

Through strategic diversification into poultry, maize, piggery and feed production, Rubaire has built a self-sustaining enterprise that supports his family, creates jobs and supplies farmers across western Uganda.

Based in Kitumba Ngombe village, the 40-year-old entrepreneur began his farming journey in 2014.

“My wife, Annet Kabasinguzi, and I were both instructors at a technical institution. Our salaries were meagre, but we had a vision to grow beyond our limitations,” Rubaire recalls.

Determined to create a better future for their two daughters, the couple saved for five months and raised sh1m. With sh700,000, they purchased 200 layer birds; the remaining sh300,000 went into feed and constructing a basic shelter on a 35 x 100-foot plot.

Starting small, big dreams

Poultry was a practical choice — affordable, manageable, and in high demand. The couple did not quit their jobs immediately.

“We needed to feed the chicks,” Rubaire says.

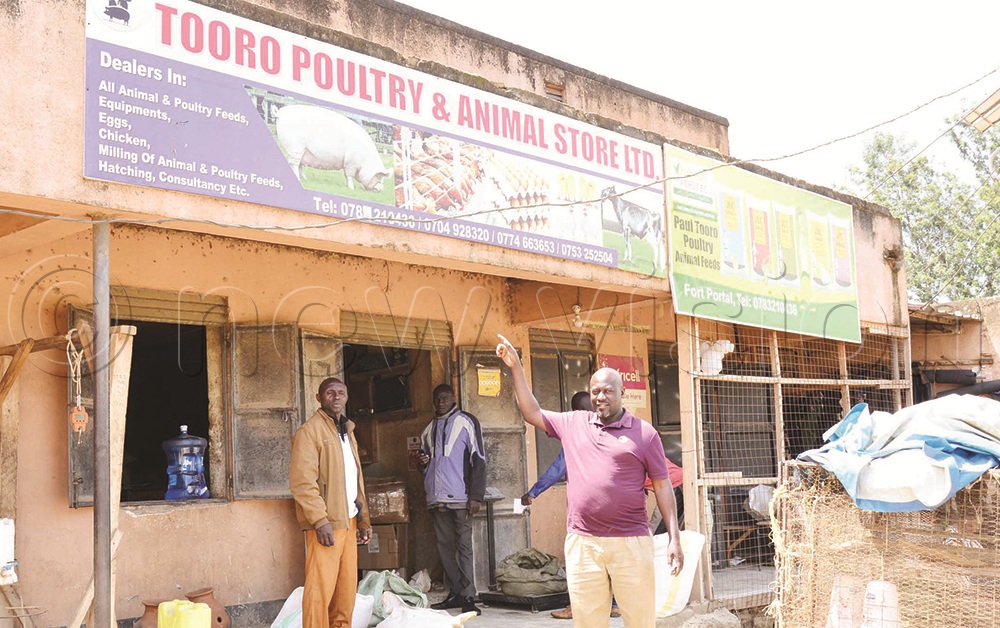

Tooro Poultry and Animal Stores Ltd in Kabarole district. Rubaire attributes his success to adopting excellent management practices.

However, their daily routine changed: mornings were for cleaning, feeding and inspecting the coop before heading to work. Their house help took over during the day and evenings were reserved for planning and care.

Despite earning less than sh200,000 combined, they used their salaries to buy chicken feed. Within six months, the business was self-sustaining.

“We hardly lost any birds,” Rubaire says proudly. Soon, they were collecting six trays of eggs daily, which Rubaire delivered to nearby shops on his motorcycle.

Turning point

Kabasinguzi recalls the moment she realised their poultry venture was more than a side hustle.

“It had always been Rubaire’s dream — even before we had land, he talked about chickens. At first, I did not share his drive, but now I do.”

The real turning point came during the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020. With many Ugandans exploring new income sources, demand for chicks soared.

“We went from a few hundred to selling nearly 2,000 chicks a week,” Rubaire says.

By 2021, the farm was earning more weekly than his monthly salary. He resigned to focus on farming full-time.

Scaling up: layers unit

Today, the poultry unit boasts over 3,000 layer birds, including high-yielding white ones imported from Turkey. Rubaire invested sh2m in the first batch as a trial and was impressed by their performance.

“They are more reliable than local breeds and consume less feed, while yielding a higher output,” he says.

His goal is to fully transition to Turkish stock within a year. The farm produces 90–100 trays of eggs daily, sold at sh11,000–sh11,500 each. With a shop in Fort Portal town and direct farm pickups, Rubaire earns about sh990,000 daily. After reinvesting sh650,000 in operations, he retains a gross margin of sh340,000.

Incubation and brooding

Rubaire has built a self-sufficient poultry cycle with a 12,000-egg capacity incubator.

“We set 3,000 fertilised eggs weekly,” he explains.

Eggs take 18 days in the setter, then moved to a hatcher until day 21. At full capacity, the farm produces 12,000 chicks every four weeks.

Chicks are moved to a brooder unit for warmth, feeding and are also vaccinated. They are sold at three to six weeks, priced between sh6,000 and sh8,000 depending on their age.

Rubaire and his wife Kabasinguzi at their feed shop.

Alex Araali, a trader in Fort Portal, says Rubaire’s system supports other farmers with good chicks.

Feed milling and distribution

To reduce costs and ensure quality, Rubaire mills his own poultry feed using a portable unit. He sources maize, cotton cake, sunflower seedcake and soya, which are dried, cleaned and milled.

“We mix concentrate with maize bran, sunflower, and soya for balanced nutrition,” he says.

Milling services are offered to neighbouring farmers at sh100 per kilo. Rubaire also runs a feed shop in Fort Portal, serving clients from Kasese, Kamwenge, Bundibugyo, Kagadi districts and across the Congo border.

Piggery unit

Rubaire treats pig farming with equal seriousness. He rears Large White and Landrace breeds, known for their rapid growth and high meat yield. His piggery currently houses over 15 mature pigs and several piglets.

“For pigs to grow well and fetch good prices, they must be fed properly, given clean water and housed in a dry, ventilated shelter,” he says.

A dedicated caregiver manages daily feeding, cleaning and monitoring.

Maize farming for feed security

To reduce reliance on commercial feed suppliers, Rubaire manages a 10-acre maize plantation.

“We realised that relying on external suppliers was not sustainable, so we started growing our own maize,” he explains.

He harvests around 200 bags, which are dried and milled into flour — a key ingredient in poultry feed. Through continuous cropping, Rubaire ensures a steady supply of feed, reduces costs, creates jobs and maintains quality.

Eucalyptus for construction

Rubaire also grows eucalyptus trees on two acres.

“We use these trees mainly for construction. Whenever we need to expand or repair poultry houses, we harvest from our plantation. It saves costs and ensures strong structures,” he says.

Strategic growth timeline

Rubaire’s agribusiness has grown in phases as follows:

- 2015: Established a feed shop

- 2018: Planted eucalyptus trees n2019: Registered Tooro Poultry and Animal Stores Ltd

- 2021: Launched maize farming and piggery projects

Each venture was carefully planned, with capital directed toward infrastructure, quality inputs and sustainable management.

Farm management practices

Rubaire attributes his success to strong management and consistent routines. He enforces strict biosecurity measures, allowing only disinfected, authorised visitors into poultry houses.

“Regular cleaning and timely vaccinations are non-negotiable,” he says.

Security is a priority, with trained personnel and dogs guarding the farm, especially at night. Rubaire also maintains detailed records of egg production, feed usage and expenses. His daughters assist during school holidays, learning business values early.

Marketing and distribution

Rubaire’s shop in Fort Portal serves as a distribution point for chicks and eggs; sales hub for poultry feeds and a consultation centre for farmers seeking expert advice.

He stocks feed concentrates and ingredients like maize bran, which are milled and mixed on-site.

“We ensure every feed mixture matches the birds’ age and nutritional needs,” he says. This precision leads to better poultry performance and strong customer loyalty.

Financial sustainability and monthly returns

Rubaire’s enterprise generates an average net profit of sh10m per month, supporting his family, staff salaries and reinvestment into the farm. Challenges like disease outbreaks and fluctuating feed prices arise, but Rubaire has built a resilient system.

By balancing operations — hatchery, feed shop, egg sales — and maintaining strict records and biosecurity, he ensures the business can withstand shocks. Regarding funding, Rubaire started with personal savings, but as the business grew, banks took notice.

“Now they approach us,” he says.

He takes loans strategically, mainly for infrastructure and equipment.

“Good financial discipline has made us a trusted partner to several institutions.”

What makes him tick?

Rubaire credits his success to continuous learning and adaptability.

“I attend workshops, research online, and visit other farmers. We cannot afford to remain stagnant,” he says.

Dan Kubanja, a local resident, says: “Rubaire’s farm started small but has grown into something we are proud of as a community.”

Community impact

Rubaire’s work has created jobs and supported over 100 farmers through mentorship. His company serves an average of 50 customers daily, providing reliable access to quality feeds and farm inputs.

Community members like Annette Tusiime praise him for empowering youth and women with practical knowledge and market linkages.

His efforts have strengthened local supply chains and boosted household incomes. He also avails his mill to other farmers at a modest fee.

“We charge sh10,000 to mill 100kg, that’s sh100 per kilo,” he says.

He adds the machine is also availed to neighbours and farmers from nearby communities who need milling services.

Overcoming challenges

Rubaire acknowledges persistent risks like theft, feed price fluctuations and disease outbreaks.

“Losing one tray of eggs daily means sh300,000 lost monthly,” he says.

To counter this, he hires honest staff, installs surveillance and stockpiles feed. “We do not just react — we plan,” he says.

Vaccination schedules, health checks and feed reserves help maintain stability.

Achievement, plans

Harriet Tusiime, a businesswoman, calls Rubaire’s farm “one of the most productive in our village.”

With 2,500 birds and a busy feed shop in town, his journey from a sh1m start-up in 2014 to a formal enterprise is inspiring.

Rubaire now owns three acres in Fort Portal and 10 acres in Kyenjojo district for maize farming. He has built modern poultry houses, a feed mill and an incubation unit. His company is formally registered, with both him and his wife as directors.

“We own our space and operate formally. That earns us credibility, access to finance, and long-term growth,” he says. Looking ahead, Rubaire plans to establish a full hatchery, expand into goat farming and mentor youth in agribusiness.