Bank of Uganda Anniversary Supplement

In July 2011, the Bank of Uganda reformed its monetary policy

The rise of Bank of Uganda

By Pascal Kwesiga

August 15, 1966 is a signifi cant date in the annals of Uganda's banking industry. It is the day the Central Bank issued the fi rst Ugandan shilling, with sh100 as the largest denomination. Today, the largest denomination is sh50,000.

The day also marked the commencement of the operations of Bank of Uganda (BOU), having been set up by an Act of Parliament on May 24, 1966. The Act received presidential assent on May 28, 1966, four days after its passing by the House.

Although it was apparent even before independence in 1962 that Uganda ought to have an independent Central Bank, for some reasons, BOU was set up four years later. Before 1966, Uganda was a member of the East African Currency Board (EACB), which had been established by the British colonial administration in 1919.

EACB, a single monetary authority for East Africa then, issued a single currency for the three countries - the East African shilling. The main task of the board, which had its headquarters in London, was to issue and redeem the East African currency in exchange for the UK's pound sterling.

The East African shilling was pegged to the British pound sterling and the value was sh20 per pound. The board had initially been set up to serve the British colony of Kenya and its protectorate of Uganda, but its mandate was expanded to include Tanganyika in 1920 and Zanzibar in 1936. The colonial administration later extended its services to Somaliland in 1942 and Eritrea, Ethiopia plus Aden in 1943.

As the independence of the East African states appeared to be on the horizon, the board was repositioned and its headquarters transferred to Nairobi from London. However, after Tanganyika gained independence in 1961, Uganda in 1962 and Kenya in 1963, it became clear that EACB could not serve the interests and aspirations of the newly independent nations.

There was pressure in the new sovereign states to establish independent central banks. A report from the central bank of the Federal Republic of Germany recommended a two-tier system that would see each country set up a state bank to carry out the functions of a central bank.

It also proposed a Central Bank for East Africa to supervise the operations of state banks. But the concept suffered a stillbirth after countries questioned the extent to which national sovereignty could be shared to achieve a coherent policy on monetary matters and rejected the idea of a heavily decentralised bank.

How BOU was set up

According to information from BOU, on February 2, 1965, Uganda indicated its intension to establish several fi nancial institutions, including the BOU to handle central banking functions. A few months later, the three East African countries, on July 10, 1965, offi cially announced their plans to set up independent central banks.

At its inception in Liverpool House on Parliamentary Avenue, the Central Bank had four departments - the general manager's department, comprising banking and currency, accounts and public debt; secretary's department, exchange control and research departments; with a total number of 56 employees. The bank's supervision department was set up in 1968, while the accounts division in the general manager's department was elevated to a department.

The development finance, internal audit, foreign operations, external debt management office, agricutural secretariat, security, management information system and medical departments were created between 1977 and 1987.

The number of staff had grown to about 2,000 and the departments to 14 by 1991. The bank re-organised its departments into six functions, with each headed by the executive director. However, scores of employees who had been recruited earlier were relieved of their duties under the voluntary and involuntary schemes between 1994 and 1995. Yet the number of departments grew from 17 in 1995 to 21 in 2005 for greater efficiency.

Turbulent past

In a document published at BOU's 40th anniversary in 2006, Leo Kibirango, who served as Central Bank governor between 1980 and 1986, said that his work at the Central Bank gave him a rare opportunity to participate and contribute to national economic management under four radically different governments.

First, under the short-lived era of the Military Commission, four years under Obote II, a short spell under Tito Okello regime and nine months with National Resistance Movement (NRM). He said one of the regimes had leaders who threatened to invade BOU to deal with ‘Bwana Foreign Exchange' who they accused of causing a public outcry due to his persistent absence from duty.

"In the same vein, Mr. Bank Credit was problematic and not readily accessible, precipitating tension between Bank of Uganda offi cers charged with the responsibility relating to banking credit, leading to gun-trotting and trigger-happy military and intelligence men eager to do target practice on living tissue of those labeled as economic saboteurs at BOU," Kibirango wrote.

He said managers and executives fl ed for their lives in the extreme circumstances. In one of the BOU's documents, the period between 1966 and 1971 is classifi ed as having been characterised by creative exuberance; 1972 and 1979 by the downside, 1980 and 1985 by reincarnation, 1986 and 1988 by experimentation and 1989 and 2006 by the liberal spirit.

The period between 1966 and 1971, described as a time of creative exuberance by the Central Bank, was characterised by the ‘move to the left' ideology and Nakivubo Pronouncements that intended to increase the nationalisation of foreign businesses.

The May 1, 1970, Nakivubo Pronouncement was a commitment issued by the then president, Milton Obote, in which he said his Uganda People's Congress (UPC) government would increase the nationalisation of major industries as part of a move towards socialism which was described in the Common Man's Charter as ‘the move to the left'.

With immediate effect, the president announced that the government would take control of 60%, up from at most 51% of over 80 corporations in Uganda. The pronouncement implied that the foreign businesses that included, among others, banks, insurance companies, manufacturing and mining factories and plantations would be run by state corporations, trade unions, municipal councils and cooperative unions.

The move stopped investment capital inflows and compelled investors to take their money out of the country, leaving disastrous consequences on the economy. Obote's move, however, was a debacle as it did not achieve the intended objectives.

The Central Bank responded by intensifying exchange controls and extended them to the other East African countries. The Uganda Argus March 27, 1971 issue quoted the chairman of Barclays Bank, Sir Frederick Seebohm, as saying: "No one questions the right of governments to nationalise within their territory...But to nationalise by instant decree and without any prior consultation is, to say the least, an unfriendly gesture, which is not likely to create a feeling of confidence among potential foreign investors."

The Asians who were aggrieved by Obote's move supported his overthrow by the then army commander, Idi Amin, in 1971. The distinct characteristic of the 1972 to 1979 ‘downside period' was the ‘economic war'. The policy that ushered in the economic war under Amin, was crafted to deal with what the government called economic agents who ‘milked the cow without feeding it'.

The economic war saw the expulsion of Asian investors, who Amin accused of exploiting the population by hoarding wealth and goods. The property of Asians, including factories, farms and estates, was reallocated to inexperienced Ugandans and government corporations ushering in a period of significant economic collapse. Banking was one of the sectors that were terribly affected by the economic war since Amin's decision struck at the heart of the economic lifeline of the country.

The banking industry contracted significantly, with many of the commercial banks closing their upcountry branches. During this period, BOU established a total exchange control regime, with no foreign exchange, leaving the country without authority from the Central Bank, save for diplomatic remittances from external accounts.

The Central Bank also directed that all expropriated businesses bank with Uganda Commercial Bank (UCB). "In these circumstances, all other foreign banks closed their upcountry branches, which were duly taken over by UCB. The Bank of Uganda protested in writing that UCB did not have the capacity to expand rapidly, as this would stretch its management capacity," the BOU says in one of its documents.

But the government ignored BOU's advice. Against BOU's prescriptions, the government continued borrowing and the debt burden reached 70% of the budget. In a 1975 annual report to finance minister, the BOU expressed reservations about the country's dwindling reserves. But the minister told Amin that the Central Bank was embarrassing the government by publishing information likely to hurt the establishment's credibility.

Bank of Uganda stopped publishing the annual reports. The country was engulfed in a debt crisis during which ministers and other government officials contracted debts without recording them in the national debt register.

It took several years and substantial resources to update the national debt register. "For a long time, the Bank of Uganda was not able to write its books of accounts and it took technical assistance and loss of face to write up the books of accounts," BOU states.

The country was hit by unprecedented levels of inflation during this period, but BOU could not effectively bring it down because its advice was not heeded. However, UCB did not take over the accounts of the commercial banks upcountry because it did not have the resources to offer the badly needed credit to farmers.

The period between 1980 and 1985 (reincarnation), according to BOU, was the time of ‘beginning from where we left off'. The reincarnation episode, according to the Central Bank, was characterised by a return to fi nancial programming, with technical and fi nancial support from International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank and other donors. Benchmarks, including the quantitative monetary aggregate and a dual exchange regime consisting of Window I (priority imports) and Window II (luxuries), were established.

The main focus of the bank during this period was to meet the quarterly monetary aggregate benchmarks and budgetary fi nancial limits. As Uganda's journey to economic recovery started taking shape, there was noticeable growth in the investors' confi dence and the banking sector started to get back onto its feet gradually.

The Central Bank says the period between 1986 and 1986 was shaped by point number fi ve of the ten-point programme - building an independent, integrated and self-sustaining economy. The major policy pursued during this ‘experimentation episode, according to BOU, was the currency reform recommended by international and local experts.

Although the number of commercial bank branches, which were around 300 in 1970s, had greatly reduced as a result of tough economic times, about 90 branches had been re-established by 1988. The number of commercial bank branches continued to increase slowly in the years that followed due to increased banking activity.

According to BOU, the time between 1989 and 2006 ushered in what it calls the liberal spirit manifested in the policies geared towards liberalising the markets, prices and monetary instrument.

As a result, in 1989, exporters of non-coffee exports were permitted to retain the proceeds on foreign exchange accounts and in 1990, foreign exchange bureau were licensed to commence business. The ‘liberal spirit episode' saw the progressive dismantling of restrictive quantitative controls as instruments of monetary policy and use of indirect monetary instruments for monetary policy management.

The Central Bank took over several indigenous commercial banks that were declared insolvent during the massive restructuring scheme in the banking sector between 1990s and 2000. Some of them were sold or liquidated.

The banks included Uganda Co-operative Bank, Greenland Bank, International Credit Bank and Gold Trust Bank. Uganda Commercial Bank, which hitherto dominated commercial banking business, was privatised during the same period.

However, from 1986 to date, the country has enjoyed relative political and economic stability for the Central Bank to perform its cardinal activities of issuing the national currency, regulating money supply through monetary policy as well as supervision and regulation of fi nancial institutions.

Other activities are the management of Uganda's external reserves, external debt and advising government on fi nancial and economic issues. Uganda has witnessed exponential growth in foreign exchange reserves due to the liberalisation of foreign exchange markets, introduction of interbank foreign exchange market, fiscal discipline, improve monetary policy formulation and implementation, coordination between fiscal and monetary policies.

These improvements, coupled with sound macroeconomic policies, have attracted substantial donor support in balance of payments and budget support. Bank of Uganda has managed to deal with the infl ationary pressures and maintained controls on money supply.

The money supply has potential to exert pressure on the foreign exchange rate, which automatically affects the value of international reserves. Bank of Uganda now has branches headed by managers in Kampala, Jinja, Mbale, Gulu and Mbarara towns. It also has four currency centres, headed by currency offi cers in Kabale, Fort Portal, Arua and Masaka towns.

Uganda's road to economic recovery

By Edward Kayiwa

In May 1987, the Bank of Uganda embarked on a journey to revive the country's macroeconomic stability, which had been eroded by years of war and business stagnation. The local unit, at the time had been severely downgraded, with inflation shooting through the economy's roof.

There was almost no foreign exchange in the country. The shilling exchanged at 1,450 against the US dollar, before the new National Resistance Movement Government introduced a new shilling, worth 100 old shillings, along with the 76% currency devaluation.

There was an urgent need for an effective monetary policy at the time. "To convert the old currency into the new one, two zeros were knocked off, that is to say, one new shilling was equivalent to 100 old shillings.

The measure helped to reduce excessive liquidity in the economy and restore the value of the Shilling that had been badly battered by the numerous economic distortions of the 1970s and 80s," says Louis Kasekende, the deputy Bank of Uganda governor.

Monetary policy refers to the use of various instruments under the Central Bank's control to regulate and influence the availability, cost use of money and credit in the economy. The goal of monetary policy is to achieve low and stable inflation, maintain a stable competitive exchange rate and support economic growth.

Secondly, a currency conversion tax was also levied at a rate of 30%, which helped to further reduce the supply of money and also availed the Government some quick revenue to finance its budget deficits that had expanded as rapidly as they are doing today.

Bank of Uganda in 1966

Bank of Uganda in 1966

Soon, both the elite and illiterate citizens started complaining that inflation was still quickly eroding the new currency's value and as a result, it was revised to a rate of sh60 per $1. "After that, the money supply continued to grow at 500% per annum, until the end of 1987. In July 1988, the Government again devalued the shilling by 60%, setting it at sh150 per US$1," he explains. By the end of 1988, further devaluation of the unit had been done, exchanging at sh165 per $1, to sh200 per$1 in March 1989 and sh340 per $1 by the end of 1989.

By late 1990, the official exchange rate was sh510 per $1. In 1995, the new constitution re-affirmed the Bank of Uganda as the county's Central Bank, thus mandating it with macro-economic stability.

In July 2011, the Bank of Uganda reformed its monetary policy framework to meet the challenges of macroeconomic management generated by the transformation of the economy over the previous decade.

"It was then that we introduced the Inflation Targeting Lite (ITL) monetary policy framework, under which we determine a Central Bank Rate (CBR), which is intended to guide short-term inter-bank lending rates and thereby influencing the marginal cost of funds for commercial banks," Kasekende says.

According to Kasekende, the Bank of Uganda uses regular interventions in the money market to ensure that the seven-day interbank rate is as close as possible to the CBR. He says the CBR is set once a month and is publicly announced, so that it clearly signals the stance of monetary policy during the month.

"It is set at a level which is consistent with moving core inflation towards BOU's policy target of 5% over the medium term," he says. The Bank of Uganda, according to Adam Mugume, the BOU executive director for research also employed the inflation targeting tool, which is an institutionalised commitment to price stability as a goal of monetary policy.

"This has helped the BOU in the development of an approach to the conduct of policy that focuses on a clearly defined target that assigns an important role to quantitative projections of the economy's future evolution in policy decisions, and that is committed to a high degree of transparency as to the goals of policy, the decisions that are made and the principles that guide those decisions," he says.

Inflation benefits

- It preserves the purchasing power of people's money and savings.

- Consumers and businesses are able to make longterm plans and investment decisions because they know that their money resources will not lose purchasing power in the foreseeable future year after year. Low and stable inflation also encourages savings.

- Interest rates, both in nominal and real terms, would be comparably lower, thereby encouraging investment and improved productivity, as well as enabling businesses to prosper in the period of stable prices.

- It enables businesses and individuals not to overreact to short-term price pressures by seeking undue price and wage rises, assuming long-term stability prevails.

Innovations to boost microfinance firms

By Owen Wagabaza

There is growing evidence indicating that climate change is threatening the world's environmental, social and economic development, including the agricultural sector. Mark Mwanje, a resident of Busandha village in Kamuli district, was in despair after he lost his four acres of maize after long droughts hit the district last year.

"This was my only hope. I was expecting to get a bumper harvester from which I would take care of my family and pay my children's school fees. I do not know what to do next" he said. Lovisa Khauda's story was no different; she had lost her maize, beans and groundnut gardens to drought on two acres of land.

"I was expecting to get about sh2m from the harvests this season, but now I cannot get even sh100,000, she said. In Uganda, climate change and increased weather variability has been observed and is manifested in the increase in frequency and intensity of weather extremes including high temperatures leading to prolonged drought and erratic rainfall patterns.

And the changing weather patterns have made it difficult for farmers in the country to plan for farming seasons using the traditional knowledge about the two planting seasons a year. However, with financial institutions now coming up with loans for agriculture implements like irrigations, the future looks bright.

According to Wilson Twamuhabwa, the chief executive officer of UGAFODE Microfinance Ltd, the major role of a central bank is ensuring the macroeconomic stability of a country and our prayer is that Bank of Uganda continues being independent in steering the macro-economic stability of the country.

"When the macro-economic environment is poor, international banks lend us money pegged on the treasury bills, yet treasury bills are usually high. This is the reason interest rates from banks are ever high. A stable macro-economic environment comes with a lot of investor confidence and a good investment climate," Twamuhabwa says.

He calls on the Central Bank to continue championing consumer protection and financial literacy, saying this is the only way the country will achieve economic progress. "As Uganda looks forward to becoming a middle income country by 2020, the need for financial literacy is critical as it helps in improving the quality of life and enhancing financial inclusion in the country. If people have the knowledge, skills and confidence to manage their finances, economic prosperity becomes attainable," he says.

Role of financial institutions

According to Twamuhabwa, banks play a big role in the development of the economy. "We, for example, play a big role in the promotion of financial inclusion. Microfinance institutions reach many areas and if you are talking about developing people, there must be financial institutions from where people can save or borrow money to do business," he says.

Twamuhabwa adds that banks provide avenues for people to do business; notably through agricultural financing, macro business funding, small business enterprises, the health sector, infrastructure as well as education.

"We also pay taxes as an institution and employ people, who pay taxes. We thus play a big role in economic development, most importantly through complementing the Government in promoting development programmes as we work as intermediaries for financial provision," Twamuhabwa says.

The challenging market

The financial market is competitive and challenging, but we nevertheless manage since ups and downs are a part of running a business. Twamuhabwa cites the example of a client who acquires an agricultural loan to grow maize, but due to drought, a client may fail to recover the money, thus paying back the loan becomes a problem.

The market is also currently characterised by post-election fever which comes with a low investment climate. To address such challenges, Twamuhabwa says they have focused on innovations. "We have for example adopted what we call full value chain where we provide everything that a client would want to have to make his or her business a success.

We for example provide irrigation implements so that when we are funding a farmer, we fund a complete chain. We have also gone as far as finding markets for our clients," he says. The bank is also supporting infrastructural development in areas that are inaccessible. It has also brought on board technology with the aim of reducing the operation costs.

He, however, says there are challenges that are beyond their control, notably the postelection fever, infrastructure development and electricity provision as many a time; they operate on generators in areas with no electricity.

Maintaining competitive exchange rates

Stephen Mulema, Bank of Uganda's director of financial markets explains to Benon Ojiambo how the central bank ensures competitive exchange rates and why it is crucial for the economy

What is an exchange rate regime?

The exchange rate refers to the price of a nation's currency in terms of another currency. Most exchange rates use the US dollar as the base currency and others as counter currencies because world trade is denominated in the dollar. An exchange rate regime is the system that a country's monetary authority, generally the central bank, adopts to establish the exchange rate of its own currency against other currencies. Each country is free to adopt the exchange rate regime that it considers optimal for macroeconomic stability and growth.

Take us through the different exchange rate regimes that Uganda has had over the last 50 years and why each of them was chosen at the respective time

When the East African Currency Board was created in 1919, the East African Shilling was pegged to the British pound (£). The pegging of the currency used in Uganda to the pound continued even after the establishment of the Bank of Uganda.

In fact, on November 18, 1967 the devaluation of the Great British Pound GB£ by 14.3% caused an initial loss of sh29.8 million (approx. £800,000) in Uganda's foreign exchange reserves and a decline of the Bank's external reserve ratio to 36.64% from the mandatory 40% stipulated in the Bank of Uganda Act, 1966.

After this shock, Uganda moved some of its foreign exchange reserves into US Dollars. Uganda continued to be a member of the Sterling Area (a group of countries that either pegged their currencies to the pound sterling, or actually used the pound as their own currency) till the collapse of the Bretton Woods exchange rate system on August 15, 1971.

Nonetheless, the country continued to use some form of fixed exchange rate regime till September 1993 when the exchange rate and current account were liberalised. The liberalisation of the current account was followed by the liberalisation of the capital account in November 1997. Today, the Bank of Uganda operates a floating exchange rate regime in which the exchange rate is determined by the forces of demand and supply.

What impact has it had on maintaining a competitive exchange rate?

A floating exchange rate regime allows the country to adjust to the external shocks easily. In case of an imbalance in the balance of payments, the country's economy is better placed to respond to such shocks compared to a situation of a fixed exchange rate regime. Because of this, the economic agents can plan their activities with a long term view of the likely direction of the economy without any worries as to whether an administratively set exchange rate may be a source of unanticipated price movements.

What are some of the challenges that have been met while ensuring competitive exchange rates for the economy?

Over the years, the exchange rate of Uganda has been depreciating due to periodic current account deficits, that is, Ugandans importing more than they export in terms of value. In the recent past, episodes of exchange rate depreciation occurred in 2008/09 as a result of offshore capital flight and low global commodity prices; 2011/12 due to hikes in global oil prices; and 2015/16 on account of volatility in international financial markets spurred by Chinese economy re-adjustments.

How has BOU handled them?

The deficit on the current account of the balance of payments has widened from less than $300 million in 2005/06 to $2.3 billion in 2014/15 on account of a higher increase in the imports of goods and services that have dwarfed the increase in the exports and tourism. Surpluses in other components of the balance of payments will continue to support the balance of payment. In addition, government industrialization drive and investment in infrastructure will go a long way in improving this challenge.

Currency centres keeping cash in steady supply

By Edward Kayiwa

In August 2000, the Government passed a law that empowered the Bank of Uganda (BOU) to issue banknotes and coins in the country, and to also ensure that sufficient currency is readily available to meet demand.

Known as the Bank of Uganda Act, the law also mandated BOU to print, as well as issue and destroy banknotes and coins that are considered obsolete from the economy. Since then, the central bank has through its branches and currency centers, legally carried out this function, thus keeping money in circulation, as and when need by both the Government and private financial institutions.

"We opened a number of these branches and currency points across the country, to enable the central bank fulfil its role of storing, processing and monitoring the supply of currency to the Government and private financial institutions in the surrounding cities, towns and villages," said Christine Alupo, the director of communications at the Bank of Uganda.

According to Alupo, currency notes that no longer meet the required circulation quality standard are ordinarily collected through the currency centers, with the help of financial institutions, for destroying in Kampala.

"The same branches and currency centers also ensure that new banknotes are circulated in all the geographical regions of Uganda, in order to balance the supply of money," she said. These are located in Kampala, Jinja, Mbale, Gulu and Mbarara, Masaka, Fortportal, Kabale and Arua which is the latest currency centre to be opened.

She said the centers also maintain public confidence in the currency by ensuring that there is always adequate stock of banknotes and coins available in all denominations for public and commercial banks use.

"The centers have also helped the Government maintain a low annual growth rate in the sums of money outside of banks, which in turn, has helped to check inflation," says Ishta Kutesa from the BOU communications office. Kutesa says the centers also provide a safe and convenient place to store money and also maintain minimum reserves requirements for financial institutions.

Minimum reserve requirements are central bank regulations that set the lowest cash reserve balances of customer deposits and notes, each commercial bank must hold as reserves. In Uganda, the requirement for commercial banks is set at one million, two hundred and fifty thousand currency points (sh25b), while that for microfinance institutions is set at twenty five thousand currency points (sh500m).

Kutesa said the centers are also responsible for processing deposits from the public to accumulate stocks for redistribution while isolating dirty and mutilated currency for destruction

BOU score at 50, what next?

By Stephen Kaboyo

Bank of Uganda has over the years transitioned towards a bigger market orientation in which the market has become an important mechanism in generating economic growth. In addition, it has played an important role in the development of the fi nancial system.

A robust fi nancial system constitutes an essential foundation for sustainable economic growth as it enhances the effi ciency of fi nancial intermediation, contributing towards lower transaction costs and increased competitiveness.

Furthermore, BOU has done well to put in place the key building blocks of the fi nancial infrastructure, such as the payment and settlement system, the development of money and bond markets, implementation of financial reforms that have allowed for integration with global financial system.

In the recent years, BOU has been at the forefront of promoting fi nancial inclusion. Financial inclusion is a key component for an economy to achieve a more balanced growth and thereby increase the prospects for a more sustainable growth path.

In its 50 years of existence, BOU has built a reputation for intellectual rigour, credibility and independence. Because of this, it is has driven important and challenging reforms in the economy. In Uganda, the focus is on the Central Bank.

To provide it with intellectual capacity and resources and capacity to undertake multi-faceted roles that extend beyond the core mandate of price stability. Looking ahead, there is still much to be done, the business of the Central Bank is an unfinished business, there will always be new challenges emerging.

Among the future challenges that I see, is the sustainability of the prevailing growth model given the not well diversifi ed economic base, the rising indebtedness linked to the massive infrastructure requirements, management of the oil resource among others. Much of this work will involve interface with other players in the public sector.

The participation of the Central Bank in many of these agendas will require careful boundary management and safeguarding the independence of the Central Bank's.

The writer is the CEO

Alpha Capital Partners and Chairman Uganda

Telecommunications Limited

Financial literacy essential for Uganda's development

By Owen Wagabaza

As Uganda moves towards achieving the National Development Plan's vision of transforming Uganda from a peasant to a middle class income economy by 2020, the need for financial literacy is immense. Financial literacy is recognised as a critical factor in improving the quality of life and enhancing financial inclusion in Uganda.

Financial literacy is defined as having the knowledge, skills and confidence to manage one's finances well, taking into account one's economic and social circumstances. According to the Bank of Uganda (BOU) website, one of their most important role is to ensure consumers make informed financial and economic decisions that ultimately drive economic growth.

As a result, Bank of Uganda spearheaded the Strategy for Financial Literacy in Uganda, launched by then Minister of Finance, Planning, and Economic Development, Maria Kiwanuka on August 16, 2013.

The strategy was launched alongside a set of core messages on financial literacy, developed through consultation with stakeholders, tested with focus groups all over the country and translated into seven local languages. The core messages cover personal financial management, savings, loans, investment, insurance, planning for old age, making payments and understanding financial service providers.

Why the financial literacy strategy

The strategy is premised on the principles of costeffectiveness, feasibility and sustainability and has a number of objectives, among them the need to improve the ability of the population to manage their personal finances well.

The strategy also aims to equip people to protect themselves against fraud, promote a number of initiatives to strengthen financial literacy in the country, make cost-effective use of resources to strengthen financial literacy as well as improving coordination and knowledge sharing in the area of financial literacy.

To cover everyone from all corners of the country and age groups, the stakeholders came up with five major ways through which financial literacy is channelled. Among these was the financial education in schools through the incorporation of financial literacy into the primary and secondary school curriculum.

BOU uses music dance and drama in schools to champion fi nancial literacy

BOU uses music dance and drama in schools to champion fi nancial literacy

This is to be achieved through the development of supplementary materials and teachers' training, and through extension of extra-curricular financial literacy activities. Another channel is the youth.

This is through the incorporation of financial literacy into university courses, and training of community mentors who incorporate financial literacy into the activities of already existing youth clubs and associations.

The strategy also aims to reach rural areas through provision of financial literacy trainings to rural communities, capitalising on existing training and trainers. This is through the dissemination of messages through a variety of community channels, such as community radios, community councils, and many others.

There is also the provision of financial literacy at formal workplaces through presentations and trainings, as well as presentations made to informal workers through their associations. Another mode is the use of media for financial literacy through engagement of newspapers and magazines and the development of a lively and vibrant website dedicated to financial literacy.

Achievements

Over the past year, BOU has prioritised the piloting of initiatives to promote financial literacy that can empower citizens to understand financial products and services and make the most optimal decisions in that regard.

The essence of the pilots is to create a good understanding of the critical success factors before rolling out activities on a large scale. Overall, more than 26 organisations are currently implementing financial literacy activities under the strategy, and more than 150,000 people have benefitted during this pilot stage.

Another milestone has been the Incorporation of financial literacy in the on-going review of the lower secondary school curriculum. A draft syllabus has been produced including exemplary extracts for textbooks, teacher guides and assessment items.

Implementation of the revised curriculum will lead to more than 1.2 million students being taught the principles and skills of basic money management within the regular school's curriculum. BOU conducts experiential training-of-trainer sessions for individuals and entities already engaged in various forms of outreach.

So far, more than 80 trainers from the formal and informal sector have been trained. For quality control, full attendance and practical rigour are emphasised before certification as a trainer.

A training manual including an adaptation guide, a set of power point presentations and content booklets have been developed. The bank intends to scale-up the Training of Trainers, as a critical component in reaching the semi- to skilled workforce.

Borrowing from past experience of behaviour change initiatives in the country through the use of performing arts, BOU partnered with other stakeholders to co-sponsor the 2014 Annual National Secondary Schools Music, Dance and Drama festival on Financial Literacy under the theme: "Simplify Money, Magnify Life: Manage Your Money Wisely for a Better Future".

The competition involved 4,000 secondary schools in Uganda throughout the 100 plus districts divided into fi ve regions and eventually to the national level. The teachers of the performing arts were trained on fi nancial literacy core messages at national and regional level.

In captivating performances, students were able to express core fi nancial literacy learning through various creative areas such as plays, poems, Uganda traditional folk songs, Uganda traditional folk dance, African instrumental composition, Western choral singing, and contemporary dance.

The bank has also developed a website www.simplifymoney. co.ug as a repository of e-tools to enable sharing and effective dissemination of financial literacy by different stakeholders with the public. In addition, an e-learning tool for formal workplaces is being developed in partnership with dfcu Bank and Stanbic Bank.

Beneficiaries of the financial literacy programme

Although he used to earn a gross salary of over sh2m a month, Tony Kalumba, 27, lacked the knowledge to manage his fi nances. "I was a bachelor without any big responsibilities, yet I was always in debt sourced from money lenders and friends and this left me in a vicious cycle of being broke," says Kalumba.

However, after attending a Bank of Uganda organised workshop on fi nancial literacy at his workplace, Kalumba says his life has never been the same. "I was equipped with skills on personal fi nancial management, saving, loans, and the need to plan for old age, since then, I handle my fi nances with care, I have since saved up to sh2m in a period of six months, and the future looks bright," says Kalumba.

Abenakyo Zeulata has a similar story. The 36-year-old rans a small retail shop together with her husband in Nabirumba, Kamuli District. Although they served over 50 customers a day, the couple was neither saving a coin nor boosting their business.

"I think we were not managing our business well," says Abenakyo. The couple maintain that after attending several sessions on fi nancial literacy in their village, a lot has changed for the better in the last one year. "We were taught the art of saving, investing and reinvesting, as a result, our shop has grown and we are planning to make it both a retail and wholesale shop at the beginning of next year," a delighted Abenakyo says. These are some of the success stories of the fi nancial literacy programme started by Bank of Uganda in 2013.

Why Bank of Uganda's policy objective is low and stable inflation

By Christine Alupo

Formulating a country's monetary policy is extremely important when it comes to promoting sustainable economic growth. More specifically, monetary policy focuses on how a country determines the size and rate of growth of its money supply and/or cost of credit in order to control inflation within the country.

Monetary policy is a form of macroeconomic policy carried out by the Bank of Uganda (BOU) to regulate the cost, availability, and use of money with the ultimate aim of ensuring price stability.

Price stability means a low and stable inflation understood as an average annual core inflation target of five percent in the medium term as well as a stable and competitive exchange rate.

Inflation is defined as sustained increase in the general level of prices for goods and services. It is measured as a percentage increase in the general price level over two time periods. As inflation rises, every shilling you own tends to buy a smaller quantity of goods or services.

In order to regulate the cost, availability, and use of money, BOU relies on an interest rate known as the Central Bank Rate (CBR) that it sets every two months. However, the CBR has not always been the strategy employed by the BOU to manage monetary policy.

Between 1966 and 1993, the Bank was a department under the Treasury in the Ministry of Finance at a time when credit allocation, interest rate and exchange rate control were part of its remit.

After attaining autonomy in the design and implementation of monetary policy, with the passage of the BOU Statute 1993, the Bank adopted the Reserve Money Programme, which prevailed until June 2011.

In July 2011, the BOU reformed its monetary policy framework to meet the challenges of macroeconomic management generated by the transformation of the economy over the previous decade. In particular, the transformation and innovations in the financial system made the continued reliance on reserve money targeting untenable.

The reforms entailed the transition to an Inflation Targeting Lite (IT-Lite) framework for monetary policy. The primary objective of this monetary policy framework is to ensure that inflation is kept at a level that is consistent with the medium target of 5% through judicious setting of the CBR with a measure of flexibility while paying attention to developments in economic growth, exchange rate, and external stability, among other factors.

The reforms to the monetary policy framework have strengthened implementation of our capacity to be proactive and forward looking in maintain economic stability for the long term.

Benchmark

The CBR provides a benchmark and signals the direction for the market interest rates. The market interest rates may include short term interbank money market rates, government securities rates at which government borrows money from the public, and commercial bank lending interest rates.

The CBR indicates the stance of monetary policy during the two months for which it prevails. The BOU aims to have the seven-day interbank money market rate trend as close as possible to the CBR, by varying the levels of liquidity through the use of repurchase agreements (repos) and reverse repos.

If the liquidity indicators such as the level of commercial bank reserves point to a change in the seven-day money market rate far from the CBR or outside the tolerable range of the CBR, then the Bank issues repos or reverse repos to restore consistency with the policy target.

Repos reduce short term liquidity and raise the level of the interbank market rate, while reverse repos raise the supply of short term liquidity, thereby decreasing the same market rate. In August 2016, the CBR was set at 14% and will be maintained at that level or allowed to lie within the tolerance band of +/- 3%.

In its four year run so far, IT-Lite has dealt with two episodes of CBR hikes; an increase by up to 12% in 2011/12 and 6% in 2015. The former was preceded by a spike in global food prices, a sharp increase in international oil prices, and a severe domestic (and regional) drought, which together pushed annual core inflation to a high level of 30.8% in October 2011.

Recent increase The recent increase of the CBR that started in March 2015 was partly driven by the depreciation of the Uganda Shilling, which started weakening against the US Dollar from February 2014.

The forward looking nature of the monetary policy framework enabled the BoU to take pre-emptive action and contain the rise in inflation to single digits. Indeed, by the August 2016 Monetary Policy Committee meeting, the risks to inflation had diminished, thereby allowing the BoU to decrease the CBR by 100 basis points for the third meeting in a row.

Because the process, through which monetary policy affects the cost of credit, economic activity, and consumer prices, is not immediate, the impact of monetary policy actions on economy persists for about four to six quarters.

An effective monetary policy transmission mechanism requires a well-developed financial services sector that facilitates savings' mobilisation and investment allocation, thereby facilitating economic growth.

As part of its mandate, the BOU undertakes the prudential regulation and supervision aimed at maintain financial sector soundness. Supervision and regulation is performed using a risk based supervisory framework that focuses on the continuous evaluation of the financial institutions' Capital adequacy, Asset quality, Management quality, Earnings, Liquidity, and Sensitivity to market risk.

The Bank also oversees system wide safety and soundness through macro prudential surveillance and regulation. The milestones of single digit inflation, stable and competitive exchange rate as well as a vibrant financial services sector that is robust enough to withstand shocks provide the necessary foundation for inclusive and sustainable economic growth.

Efforts to have more Ugandans utilize the formal financial services sector are well underway through the financial inclusion programme divided into the pillars of literacy, consumer protection, innovations, as well as data and measurement.

Mobile Money promotes Uganda's financial inclusion

By Benon Ojiambo

It is no longer a point of argument on whether or not Ugandans have embraced the mobile money revolution, they have. Mobile money has been aided by the ‘mobile phone craze' that has taken Ugandans by storm in the recent years.

According to the 2016 Financial and Digital Inclusion Project (FDIP) report that was released by the Centre for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution in the US, Uganda is one of the highly-ranked countries performing well in financial inclusion.

This has been partly attributed to the country's strong levels of mobile money adoption that has served as the primary driver of financial inclusion. Mobile money adoption can be traced to about seven years ago, when MTN Uganda first introduced e-money services in Uganda.

Although there was slow reception in the usage of the service by the people, it later gained momentum. The number of telecom companies offering the services in the country has since grown to five. These are MTN, Airtel, Africel, Uganda Telecom and Smart Telecom.

The number of registered mobile money customers has tremendously increased from about 10,000 in 2009 to about 19.5 million as of 2015, according to the Uganda Communications Commission (UCC) statistics.

Over the years, the number and the value of transactions have been on the increase. For example, their value has risen from sh132.6b to sh24 trillion over a period of seven years. "It is fair to say mobile penetration has been the game changer in making possible the extension of financial services to an unprecedented number of people, Christine Alupo, Bank of Uganda's director of communications told New Vision.

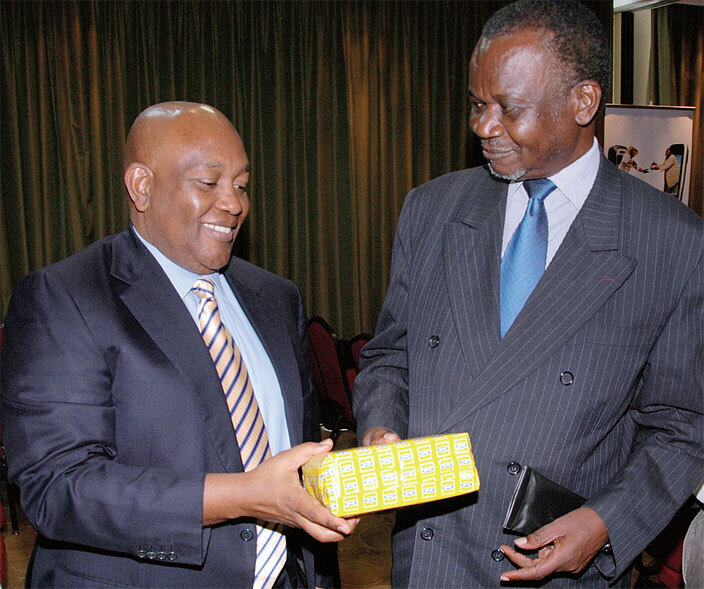

MTN chairman Charles Mbire (left) hands over a Black Berry smartphone to the then information minister Aggrey Awori, during the commercial launch of MTN mobile money at Sheraton Kampala Hotel, in 2009

MTN chairman Charles Mbire (left) hands over a Black Berry smartphone to the then information minister Aggrey Awori, during the commercial launch of MTN mobile money at Sheraton Kampala Hotel, in 2009

Although the mobile money service deserves credit in Uganda's financial literacy mileage, Alupo says the real enabler has been the technology and regulatory framework, which has ensured that the proliferation of mobile money services is not a threat to systemic stability, safety of depositors' funds and the overall process is orderly.

She singles out mobile money guidelines that were issued by the central bank to steer the actions of mobile network operators, financial institutions, mobile money agents and the public consuming mobile money services. Alupo adds that work is in progress to develop comprehensive regulations.

"Bank of Uganda and UCC are moving towards signing a Memorandum of Understanding to provide a framework for the parties to exchange information and co-operate with each other regarding the approval, regulation and supervision of mobile money services in Uganda," she said.

She also explained that efforts are under way to bring a proposal for a national payment systems law to Parliament to strengthen the regulatory framework for mobile money services. The report, however, states that efforts to reduce fraud are vital in ensuring financial stability and consumer confidence.

Several highprofile incidents of fraud may disrupt trust in Uganda's formal financial sector. For example, in 2011, (now former) employees of MTN Uganda allegedly colluded to defraud the company of over sh8b. Alupo agrees with the report that it is a global reality that there are fraudsters who try to take advantages of any loopholes in systems, but it is also the case that there are several success stories in the prevention of fraud and apprehension of perpetrators.

To mitigate fraud, on the other hand, she explains that they have the Anti-Money Laundering Act 2013, which led to the establishment of the Financial Intelligence Authority.

"There are also the steps taken by the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development and the central bank to strengthen the infrastructure for financial transactions such as the Treasury Single Account, as well as procedural rigour intended to protect the integrity of government transactions. At the level of financial institutions, they are required to invest in systems that are capable of fraud detection and interception," Alupo said.

"Sensitisation of the public and strong collaboration with law enforcement agencies are critical in this regard," she said. Alupo maintained that as a member of the global Alliance for Financial Inclusion, Uganda will continue to pursue the initiatives that seek to increase the number of people considered financially included from 54% (FinScope Survey 2013) to 70% by 2017.

The contributing pillars for this aspiration are financial consumer protection, financial literacy, financial innovations as well as financial services data and measurement. She says with the recent passing of amendments to the Financial Institutions Act 2004 to allow for agent banking, where financial institutions extend services to their customers through third parties without necessarily setting up a brick and mortar operation, future prospects of financial inclusion have been boosted.

This is so because it has the advantage of reducing both the cost of financial services and the distance covered by the public seeking to access financial services. "Overall, we expect more competition in the sector and the emergence of new products that leverage technology. The trend points at more complementarity between traditional banking platforms and mobile money," she added.

Sh2.8 trillion lost to money laundering

By Gilbert Kidimu

Most television lovers have watched the highly acclaimed television series Breaking Bad, where chemistry teacher, Walter White turns into a hard-core methamphetamine dealer. He funnels his earnings from selling illicit drugs through a series of car-wash businesses and, like most money launderers, he executes each step that by the time his cover is blown, thousands of Americans have been high on his meth.

However, money laundering is closer to Uganda than the famed television series. Money laundering is the process of creating the appearance that large sums of money obtained from crimes such as drug trafficking or smuggling, originated from a legitimate source.

You have heard similar stories in the media detailing companies that are only fronts to money laundering; businesses that do not seem profitable, but nonetheless rent premium space in the city centre or expansive warehouses in the suburbs.

The threat has become so apparent that recently, the Inspectorate of Government (IG) and the Financial Intelligence Authority (FIA) signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to share information on money laundering and other forms of illicit financial flows.

Inspector General of Government (IGP) Irene Mulyagonja and FIA executive director Sydney Asubo signed the MOU imposing a number of duties and responsibilities on the two parties as they share information in the fight against illicit financial flows.

Justice Mulyagonja says the MOU is a move to further strengthen the co-ordination between the anti-corruption bodies. She reveals that FIA has already started furnishing them with vital financial intelligence, hence the need for confidentiality and specificity of the kind of information shared.

Asubo, reasons that the involvement of the IG is crucial because corruption is the major form of illicit financial flows. Asubo adds that under the MOU, the authority will provide the IG with significant information for investigations and prosecutions where necessary.

He, however, adds that they want the integrity of the information not to be compromised through premature leaks in the media or disclosure to the targets. Both Justice Mulyagonja and Asubo agree that real estate is an area where there is a lot of cleaning of dirty money by the corrupt, arguing that getting to the bottom poses some challenges.

Asubo further reveals that FIA is carrying out a national risk assessment to identify high and low risk areas and come up with necessary interventions. Uganda loses at least 12% of its National Budget through illicit financial flows, according to FIA. That is about sh2.8 trillion, the equivalent of the entire budgetary allocation for works and roads.

How the perpetrators work

There are three steps involved in the process of laundering money-placement, layering and integration. Placement refers to the act of introducing dirty money (money obtained through illegitimate, criminal means) into the financial.

Layering is the act of concealing the source of that money by a series of complex transactions and book-keeping gymnastics, while integration refers to the act of acquiring that money in purportedly legitimate means.

One of the most common ways that laundering takes place in Uganda is when a criminal organisation funnels their illegally obtained cash through a cash-based business, slightly inflating the daily take. These organisations are often referred to as fronts.

Other common forms of money laundering include smurfing, where a person breaks up large chunks of cash and deposits them over an extended period of time in a financial institution or simply smuggles large amounts of cash across boarders to deposit them in offshore accounts, where money laundering enforcement is less strict.

The law

According to the Anti-Money Laundering Act, banks and the whole financial sectors as well as to lawyers, notaries, accountants, real estate agents, casinos and company service providers are required to identify and verify the identity of their customers and of the beneficial owners of their customers by ascertaining the identity of the person, who ultimately owns or controls a company.

They also need to monitor the transactions the business relations with the customers, as well as report suspicions of money laundering to the public authorities usually the financial intelligence unit.

It stipulates taking supporting measures such as ensuring the proper training of personnel and the establishment of appropriate internal preventive policies and procedures. According to Uganda Bankers Association, financial institutions shall not keep fictitious or anonymous accounts that they cannot identify who the owner is they shall clear customer acceptance policies and procedures, which describe the type of customers that is likely to pose higher than average risk to financial institution.

Financial institutions should not open up an account for a customer where problems of verification and identity arise. Financial institutions shall keep records on every customer, identification including copies or records on official, identification documents such as a passport and identity cards.

Financial institutions shall maintain a minimum of 10 years all necessary records to enable to comply with any information request. As a customer of a financial institution, you have the responsibility to provide all the requested information to ensure compliance with the anti-money laundering regulations.

How central banks stabilise prices

Apart from a pending presidential election, there was nothing special about the start of 2011 for many Ugandans like Rita Kyomukama, a vegetable vendor at the Ggaba market in Kampala. It all started to change after the February election as inflation rose from 5.6% to 6.4% in February 2011, before hitting a record high of 30.48% in October 2011; scaring most Ugandans and the markets along the way as prices of most essentials such as sugar and fuel hit the roof.

Kyomukama, a single mother of two noted that the rise in the cost of beef meant that she and her children could hardly enjoy it. The cost of a bunch of matooke, a staple food, had also risen by 23% between August and September 2011; in the same period, the cost of sugar went up by 36%, putting significant pressure on the household budgets of the poorest Ugandans.

Chris Rugambo, who runs a stall at Ggaba market, said at the time somebody who had been buying 2kg each of rice, peas, beans, sugar and flour for their family had been reduced to buying a quarter of that due to price increases.

Inflation targeting lite framework

Since 1993, Uganda implemented a quantity-based monetary policy framework, which worked under the assumption that there was a stable and predictable relationship between quantity of money and prices.

"The stability and predictability of both money demand and velocity is no longer certain due to the transformation of the economy over the most recent decade. In particular, there has been rapid growth and diversification of the financial system including innovations in electronic payment systems that make the accurate targeting of money quantity untenable," Christine Alupo, the Bank of Uganda (BOU) director for communications, says in a statement.

As the inflation situation started to worsen, Bank of Uganda shifted to an inflation targeting lite monetary policy in July 2011. Monetary policy is the way in which BOU controls the supply of money to ensure price stability and to protect the shilling.

The central bank can decide to target inflation through setting a benchmark interest rate, as they currently do with the inflation targeting framework. Alternatively, they could focus on controlling the amount of money in circulation, like they did before July 2011. Inflation targeting is currently being used in more than 28 countries such as in the UK, US, Canada, Japan, South Africa, Brazil and Australia.

Monetary policy is just one of the many economic policies pursued within an economy to achieve various economic goals, including high economic growth, financial sector stability and maintenance of price stability.

In order to achieve those objectives, the central bank works through the financial system, which plays a critical role in transmitting monetary policy actions to spending decisions of consumers and investors and ultimately affecting output and prices.

In addition to creating price stability, the inflation targeting monetary policy also increases transparency and accountability mechanisms through the public announcement of targets and forecasts for inflation and a policy of communicating to the public and the markets, the rationale for the decisions taken in determining the benchmark Central Bank Rate (CBR).

The CBR is a signaling rate that is announced within the first week of every two months by the BOU. The key ingredient in setting CBR involves evaluating the future projection for core inflation; a subset of total inflation with prices of things that take long to change.

The aim of the CBR is to influence international factors such as interest rates, inflation, exchange rates; output gap and capacity utilisation; domestic demand; money supply and credit extension, as well as inflation expectations.

How does the CBR work?

If BOU forecasts inflation to rise in the future, then it will increase its CBR to signal monetary policy tightening. This is aimed at forestalling the eventuality of the foreseen higher inflation through managing inflation expectations, raising the cost of borrowing to reduce aggregate demand of goods and services.

In July 2011, tightening of monetary policy was also meant to foster stability in the foreign exchange market by reigning in on the arbitrage opportunities for commercial banks, according to a statement from the central bank.

Does the CBR replace the bank rate?

No, the bank rate that existed under the previous policy framework remains, although its computation is no longer based on the 91-day treasury bill, as a reference rate. The treasury bill is a contract by which the Government borrows from banks or the public for less than a year.

The bank rate is the rate at which commercial banks can borrow from the BOU against eligible collateral for up to three months. Money is not free. The eligible collateral for borrowing from the BOU is treasury bills. Each bank has an automatic right to borrow from the BOU an amount of up to 25% of its statutory reserve requirement.

Any borrowing above that amount is at the discretion of the BOU. The rediscount rate has to do with returning a treasury bill before the entire contract runs its full course. Discounting is all about finding the current value of a future payment.

Under the inflation targeting framework, for the June 2016 monetary policy, the BOU maintained the rediscount rate at the CBR, plus a margin of 4% points while the bank rate was the CBR, plus a margin of 5% points. Consequently, while the CBR was set at 15% in June 2015, the rediscount and bank rate were at 19% and 20% respectively.

How effective is CBR?

Stephen Kaboyo, the chief executive officer of Alpha Capital Partners, says financial markets are still shallow and illiquid, which has affected the effectiveness of the CBR. "Secondly, the formal banking sector covers a small part of the economy and therefore, banking is characterised by high costs financial intermediation.

This undermines the effectiveness of the transmission mechanism," he explains. "In my view, the credibility and expectations have been the biggest achievement. Whenever BOU makes a commitment to keep inflation within the target, markets build in low inflation expectation and this helps in anchoring low inflation," he says.

Muhereza Kyamutetera, the Corporate Image chief executive officer, notes that the central bank should look beyond targeting inflation through managing demand and focus on the supply side constraints, which, according to him, are the root cause of inflation. "Inflation is not in a vacuum, the central bank should not concentrate on the demand side alone; most inflation is due to supply side constraints.

Households spend more than 50% of their incomes on food and food supply is still a problem," he argues. "I think the CBR is counterproductive, it does not support production. The central bank must look at how to stimulate production. They should look at stimulating job creation like the US Federal Reserve Department (FED) does," he says.

High interest rates

Kyamutetera notes that the CBR has resulted in Uganda having the highest interest rates in East Africa, which makes local companies less competitive in the region. He says firms from neighbouring countries could easily borrow from their countries and outcompete Ugandan firms in their own backyard.

He also says due to the high rates and resulting difficult economic environment, some banks are sending staff members on forced leave. "I know a bank branch where they are now only banking sh3m down from sh25m every day. Business is low, so staff are being asked to go on leave till the situation improves."Earnings from agricultural exports such as coffee and tea are down and the shilling has not been spared. We risk entering a recession. We are not competitive. I support the people that are agitating for an amendment of the BOU Act to make them more effective," he says.

In another statement, Prof. Augustus Nuwagaba, an economist, notes that the central bank needs to apply a carrot and stick approach to ‘discipline' the ‘stubborn' commercial banks which do not adjust their prime interest rates, the least lending rates for the best customers, in line with the CBR.

"Experience has shown that since the application of the CBR as a monitory policy tool, it has only influenced commercial banks to increase their prime lending rates. Why do commercial banks fail to respond to the reduction in CBR?" he asks.

"Why do commercial banks charge higher interest rates even for ‘old' loans acquired before the increase in the CBR?" he wonders. According to Nuwagaba, four commercial banks in Uganda command approximately 65% of the entire financial asset base.

"Such banks have the financial muscle and sufficient voice to stubbornly refuse to heed to the CBR as a monetary policy transmission mechanism," he says. Nuwagaba's proposal is for Parliament to legislate the maximum percentage points within which commercial banks can set their lending rates from the CBR as the benchmark.

He argues that this has worked in Kenya, where Parliament has legislated against high interest rates by errant commercial banks. "In Kenya, commercial banks cannot charge a lending rate beyond 4% points from the CBR. Currently, their CBR is 11%, implying that no commercial bank can charge an interest rate beyond 15%," he says.

He further says legislating lending rates will ensure that banks operate in the interest of Ugandan businesspeople, farmers, small-scale operators, teachers, health workers and other professionals who are both customers and shareholders of the banks.

No law to protect public from errant money lenders

By Jacky Achan

From legislators hiding away inside Parliament to evade arrest to teachers surrendering their Automated Teller Machine cards and consequently being reduced to beggars; the story of the tyranny of unregulated money lenders is as legendary as it goes. Unfortunately, without a competent law in place or regulator like Bank of Uganda, there seems to be no reprieve for such victims in the future yet.

The Money Lenders Act, which is supposed to regulate the activity of money lenders in the country, for some reason does not provide the much-needed guidelines on how they must operate and what acceptable rates they need to charge.

According to the chairperson of the parliamentary committee on finance, planning and economic development, Henry Musasizi, there are many loopholes in the 1952 Act.

"It is just so wrong for a money lender to charge an interest rate of 10% a month on a loan," he says. The act requires money lenders to annually obtain certificates from a magistrate who has jurisdiction over the area they operate in.

It also requires them to obtain a licence from a local authority annually, lend at an interest rate not exceeding 24% annually and draft contracts between the lender and the borrower for legal purposes. Yet with these regulations in place, only a few adhere to them.

To make matters worse, without a robust mandate, the Ministry of Finance or Bank of Uganda are toothless. Only recently during part of the activities to mark the golden jubilee of Bank of Uganda in Mbarara, the deputy governor, Dr. Louis Kasekende, cautioned Ugandans against borrowing from money lenders.

"The Central Bank does not regulate money lenders," Kasekende warned according to media reports. Musasizi admits that for the money lenders trade, the challenge has been on regulation, given the many loopholes in the Money Lenders Act.

The money lending sector is not regulated as it should be because it is dealing with money, which is a risky business and involves public interest. But even with the challenges in place, the Judiciary spokesperson, Solomon Muyita, says in 2014 alone, complainants recovered sh2.5b through the 11 operational small claims courts. Last year, another sh5.5b was recovered by complainants through 19 courts via the small claims procedure.

Even with regulation challenges, the small courts are helping the ordinary person recover their money minus the cost of using lawyers. On average, 200 cases are filed under the small claims procedure on a monthly basis and most complainants with small claims have increasingly been opting out of the mainstream court registry for the small claims procedure because it is quick and effective.

Small claims courts were put in place to fast-track simple cases in the court system that can be argued out by the complainants themselves. Muyita says the civil claims value does not exceed sh10m and besides arising out of the supply of goods and cases of rent, there are also debts to be settled.

The small claims courts, having started in 2012 in five magistrates' courts, spread across the country and are now 26 in total. "In all these courts, the small claims cases are the majority and if a complaint is brought forward, it is settled in not more than 30 days and more people are embracing it," he explains.

Muyita says as a complainant, you only need to come with your evidence and meet with the judicial officer once or at most twice, and it takes about 30 minutes to reach a settlement with the other party in a friendly environment.

"Normally, those against whom the complaints are filed do not deny the case, but are hard-pressed and seek more time to clear the debt, which is always granted. Where they default, a decision is decreed and court bailiffs are employed to identify a property worth the value of money they owe, take charge, sell it and recover the money," he states.

But still individuals and companies have lost valuable property ranging from mobile phones, laptops, cars, land and houses to money lenders as a result of not being in a position to pay back.

Different people have confessed in different media reports that most money lenders are usually bent on frustrating borrowers from paying back on time so that they can assume ownership of their valuable property, which many times cost more than the loan taken.

This is because the money lenders collateralise loans and unilaterally collect this security, creating opportunities for the malicious lenders to steal from clients. Musasizi says such acts of malice, therefore, call for tighter regulation of the money lending section to protect people's money and assets getting lost and to also safeguard against the shrewdness of money lenders.

He says the answer now lies in the Tier 4 Micro Finance Institutions Act that was passed on May 4, 2016 in Parliament. The money lending business is included in this act as efforts are undertaken in plugging loopholes in the Money Lenders Act.

The new law, if put into force, will require all money lenders to be registered and licensed by the micro finance institution. Musasizi says this will prevent all risks currently faced by borrowers dealing with the unregulated money lenders.

In addition, he says interest charged will also be regulated. Musasizi says under the new act, the new law has restrictions on interest rate. The law has placed a cap on the minimum and maximum rate of interest that can be charged by money lenders and over what duration that is not below six months to protect the borrowers from exploitation. Musasizi says the law was assented to and it only remains to be gazetted and operationalised.

"The moment the law gets operationalised, money lenders will be required to work by fresh regulations. People in money lending business will be clearly known and the microfinance regulator will be responsible for all the challenges," he guarantees.

Money lenders, self-help groups in villages, savings and credit cooperative society in Uganda (SACCOs) and micro finance institutions are all targeted by the new law to bring sanity in the money lending trade. Musasizi says though it is difficult to ascertain how much portfolio the local money lenders control because of lack of regulation, it will be possible to know how much they control with regulation.

He says the objective of the Tier 4 Micro Finance Institutions Act is to ensure that all four entities are regulated collectively for smooth operation of the business by both company and individuals to minimise or eliminate fraud.