African nations urged to do more to protect children

Dec 01, 2020

One critical observation is that while the continent has reformed in many ways, age-old problems exist and others are emerging in the context of children.

CHILDREN AFFAIRS

African governments, including Uganda's, have been urged to ramp up their efforts towards the protection of children's rights.

One critical observation is that while the continent has reformed in many ways, age-old problems exist and others are emerging, hindering the full realisation of the rights and welfare of the child.

A new report by the African Child Policy Forum (ACPF) titled 'Africa's 30-year Journey with the African Children's Charter: Taking Stock, Rekindling Commitment' indicates that progress made in this direction is "very slow".

The report, which has taken a critical look at the status of child rights in Africa, was launched on Tuesday in celebration of the 30th anniversary of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ARWC).

The charter was adopted by the then Organisation of African Unity (now African Union) in 1990 and was only entered into force in 1999 due to low uptake in the early years. To-date, 49 out of 55 states have ratified it, four of them having entered reservations.

The latest findings by ACPF look at examples and experiences from countries in all five African regional blocs, albeit focusing on nine countries in detail which represent the full range of ‘child friendliness' rankings according to the 2018 Child Friendliness Index.

Meanwhile, Uganda was recently ranked under the 'Less friendly' category on the girl-friendliness front in Africa.

The 2020 rankings were released in an earlier report by ACPF on how friendly African governments are towards girls. Here, nations were ranked under the categories of: Most friendly, Friendly, Faily friendly and Least friendly.

In her comments on their latest report, Dr. Joan Nyanyuki, the executive director of ACPF, says the Children's Charter has accelerated "a shift towards a culture in which children have become visible in the human rights, political and development discourses across the entire continent".

She talks of "ups and downs" in Africa's journey in implementing child rights.

"As the continent has made efforts to combat violence against children, child marriage and female genital mutilation (FGM), it has seen a sharp increase in sexual violence and exploitation and emerging new forms of violence in the poorly regulated online space, travel and tourism sectors," says Nyanyuki.

"While infant mortality has shown a decline unparalleled by any other region, and primary school enrolment a significant increase, access to early childhood and secondary education has remained low.

Uganda, for example, introduced Universal Primary Education (UPE) in 1997 to expand access to education, ensuring that every child enrols in school.

To guarantee access to UPE, the Ugandan government enacted the Education Act of 2008, which spells out the duties of the state, parents, the school and other stakeholders.

"While Africa has reason to celebrate some level of success, there are just as many causes for shame," says Nyanyuki, before rallying African nations to reenergize their commitment to the cause.

On budgeting for children, the report by ACPF found that despite efforts by some governments and civil society organisations to ensure that national budgets take children's rights into account, "no African country has completely integrated a child's rights perspective in their budgeting process".

This is an obligation as per General Comment 5 of the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACERWC).

Only South Africa was found to come close to doing this.

"Many countries have specific line items for children's programmes instead of mainstreaming children's rights," says the report.

Another observation is that while some African countries have made efforts to gather data on children's rights, most do not have "comprehensive disaggregated data" - and what is available is inconsistent.

Child rights organisations were also found to feel the negative ripple effects of a "hostile environment and a reduced civic space", resulting from the clampdown on civil society usually working "on sensitive civil and political rights".

The report also says that child participation in Africa remains "inconsistent, ad hoc and driven by CSOs" despite some positve developments in some nations where children's parliaments exist on top of other platforms and avenues for children's participation, including school clubs.

In many countries, children's views are "sought and taken into account in court proceedings".

Meanwhile, the island nation of Mauritius is reported to be the only African country with a dedicated children's ombudsperson. While huge strides have been made to establish independent child monitoring mechanisms, the report says that "there are significant differences in how far they engage with child rights issues".

Ethiopia, Malawi, Mauritania, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Sierra Leone and Zambia are said to have established children's desks or ombudspersons within national human rights institutions or in the office of government ombudspersons.

The new findings point to significant progress in eliminating harmful cultural practices, including female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage.

Uganda, for instance, has an anti-FGM law in place that has helped cut the number of FGM cases in recent years. According to United Nation estimates, as many as 200 million girls and women worldwide have undergone FGM.

The practice, which is common in some parts of Africa, Asia and the Middle East, involves the partial or total removal of the external genitalia.

Uganda criminalized FGM 10 years ago, with a maximum penalty of 10 years in jail.

On the legislative front, the report by ACPF underlines the "considerable progress in passing laws to enforce child rights and to make some conduct illegal".

But it adds that states have yet to reach satisfactory levels of legislative compliance due to conflicts between national law and the Children's Charter in some areas.

The areas include defining a child as a person under 18, minimum age of marriage, discrimination against girls, child labour, minimum age of criminal responsibility, criminalisation of harmful practices and juvenile justice.

Meanwhile, the report says that the establishment of such agenda-setting initiatives as the Day of the African Child is "encouraging" as it highlights "a versatile approach to child protection in Africa".

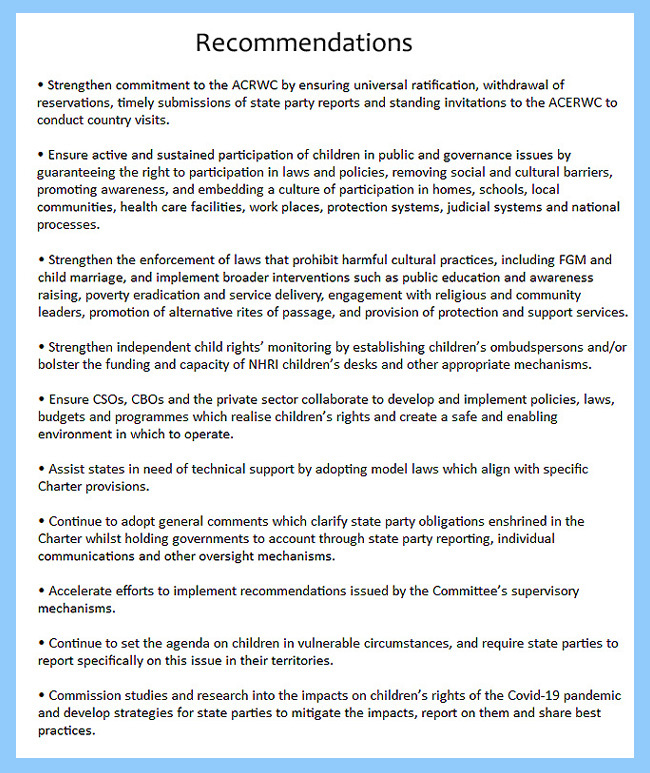

With the hope of rekindling regional and national commitment to child rights and wellbeing on the continent, the researchers are urging African Governments to reflect on the experiences of countries that have consistently remained child-friendly, including sustained efforts in the legislative, policy and political realms.

Also related to this article

Journey of Hope Walk 2019 diary: Day 12

Trafficked Karimojong girls end up with Al-Shabaab