How HIV/AIDS fight started in Uganda

Nov 05, 2018

It all started in a small fishing community. Patients lost so much weight that residents began to call the disease ‘slim’.

UNITED AGAINST HIV/AIDS

In the run-up to World AIDS Day (December 1), for the whole of November, Vision Group media platforms are airing and publishing in-depth articles about the disease.

______________________________

The memories of how a mysterious disease hit a small fishing community in Kasensero, Rakai district in 1982 are still vivid for Martin Kalema.

"Patients lost so much weight that residents began to call the disease ‘slim'," Kalema recalls.

To protect themselves from what they suspected to be witchcraft, residents resorted to administering herbs by cutting their skin using shared razor blades. The practice instead accelerated the spread of the disease and within a short time, the entire village, located along the shores of Lake Victoria, had been infected.

Prof. Nelson Sewankambo, a lecturer at Makerere University's College of Health Sciences, recollects that the then Rakai district medical officer, Dr Rwagaba (and other health workers), reported the development of a new disease that was characterised by severe diarrhoea, weight loss, fevers and itchy skin rash.

The patients also developed painful sores in the mouth, which made it difficult for them to chew or swallow.

"HIV/AIDS was first seen in wealthy people who were involved in smuggling merchandise to Uganda from Tanzania, across Lake Victoria. After the disease broke out, people associated it with witchcraft, referring to it as Omutego. They thought they were being bewitched by traders from Tanzania," Sewankambo says.

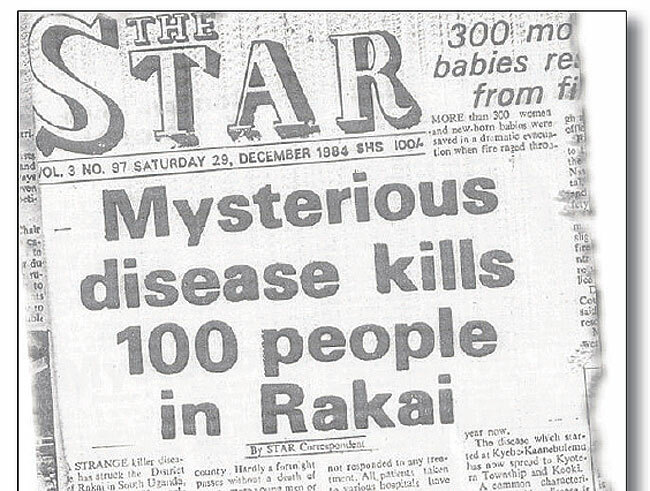

The Star newspaper carried one of the first news articles on HIV/AIDS in Uganda on Saturday, December 29, 1984.

The headline read: "Mysterious disease kills 100 people in Rakai".

Confirming the disease

Sewankambo says the health ministry put together a team of consultants, who worked with the Uganda Virus Research Institute. They visited Rakai and Masaka. They carried out investigations, but their report was incomplete.

Dissatisfied with the report, a group of medical doctors from Makerere University and Mulago Hospital, who included Sewankambo, Prof. David Sserwada, Prof. Roy Mugerwa, Dr Rwabaga, Dr William Carswell, Dr Bob Downy from the UK and Prof. Ann Bayley from Zambia, teamed up and went back to Rakai and Masaka.

They visited the wards in Kalisizo and Masaka hospital, taking the history of patients, blood samples, urine and stool.

The team also went deep into the villages to get a clear description of the disease. Sewankambo says specimen was later sent to Porton Down Public health laboratory in the UK.

The results confirmed that patients had evidence of an infection with a HTLV III virus, which at that time was found in patients in the US. In 1985, the team published a report on "slim disease" in the Lancet.

After publishing the report, more research on how the disease was transmitted was carried out.

"People thought it was spread by mosquito bites and through contact and sharing of utensils. We studied families and discovered that the disease affected couples, hence the conclusion that it was sexually transmitted," Sewankambo says.

Similar presentation

The HTLV III patients from Uganda and US presented with similar characteristics, such as Kaposis Sarcoma. The difference was that the disease here affected both male and female, while in the US, it was the gay men.

In addition, patients in Uganda had severe diarrhoea and skin rash. Sewankambo recalls that there was a registered increase in the number of patients of Kaposis Sarcoma, a kind of skin cancer that was very aggressive.

Besides, patients also had a history of Herpes Zosta, which attacked nerves across the chest, hence the name kisipi.

Uganda, being among the first hard hit countries, HIV prevalence rate was as high as 30% in urban areas and 15% in the rural areas.

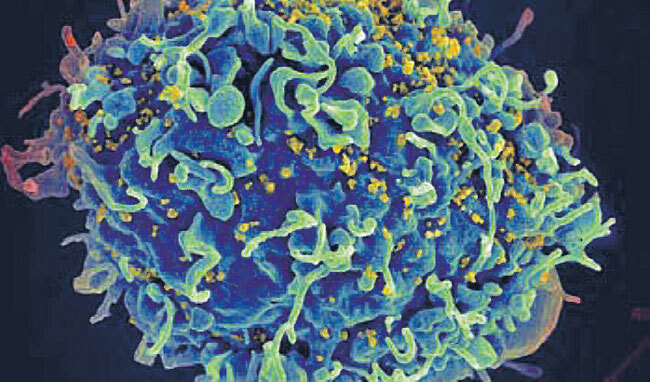

Effects of HIV virus (in yellow) on a human cell. The desease remains an epidemic

Overwhelming stigma

Sewankambo says stigma started right from the beginning.

"There was no treatment, apart from supportive care and patients were inevitably dying. The disease was affecting mainly adults, hence leaving behind orphans, which became a great concern to the country. Taking care of the orphans was another cause of stigma."

According to Sewankambo, people refused to nurse the patients for fear of getting the disease.

Dr Denis Tindyebwa, a paediatrician and the executive director of African Network For Care of Children Affected by HIV/AIDS, says by then, people in the community had a lot of misconception about causes and the mode of transmission.

"Later, when people learnt that the disease was caused by HIV and transmitted through sexual contact, they started isolating and blaming the patients for being promiscuous, which caused a lot of stigma," Tindyebwa says.

"It was a deadly disease and to be told that you had HIV/AIDS was as good as being pronounced dead," says Dr Yusuf Mpairwe, the director NAMELA Medical Laboratory.

Norine Kaleeba, the founder of The Aids Support Organisation (TASO), blames it on ignorance and fear.

She recalls that when her late husband, Christopher Kaleeba, retuned to Uganda, so many people turned up at the airport to actually see what an AIDS patient looked like. None of them dared to touch or greet the patient.

When Christopher collapsed and was admitted at Mulago Hospital, the couple suffered great stigma.

"People shunned HIV/AIDS patients to the extent of even refusing to bury them. They could not touch, sit close or share utensils with sufferers," Mpairwe says.

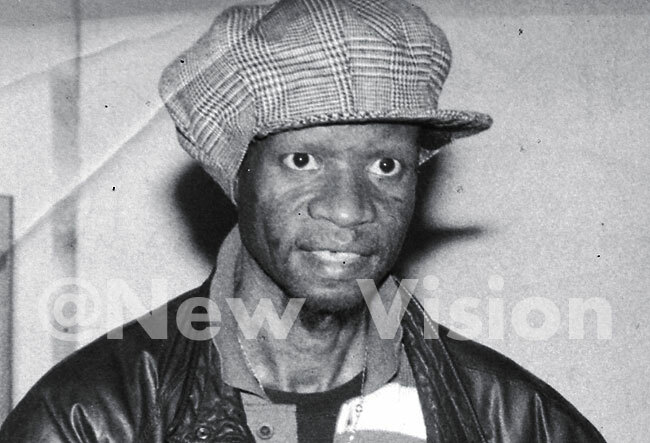

Philly Bongoley Lutaaya came out on his HIV status in 1989. (New Vision archives)

Fighting stigma

Dr Nelson Musoba, the general director of the Uganda AIDS Commission, says the 1982 government knew about the disease, but chose to keep quiet for fear of spoiling Uganda's image and scaring away tourists.

When war ended in 1986 and the National Resistance Movement came into power, the Government sent 60 army officers for military training in Cuba.

The soldiers were tested before training and 18 of them were found to be HIVpositive.

"This was the first indication of Uganda's high prevalence rate. It was later confirmed in 1989, when a report showed that nearly a quarter of the pregnant women attending antenatal care at sampled clinics were infected with HIV," Sewankambo says.

The Government recognised that the magnitude and impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic cut across all sectors of life.

It was then that President Yoweri Museveni took swift action. In October 1986, the health ministry set up the AIDS Control Programme (ACP) with support from the World Health Organisation.

It was the first ACP in Africa and later became the model of the government, which launched an aggressive open policy and media freely reported about HIV/ AIDS.

At the beginning of radio and television news, a drum would be sounded to alert the public about HIV.

Articles, cartoons, photos about HIV and sex education started appearing in newspapers, magazines and television documentaries. Posters were also pinned up, public rallies held, teachers were trained to begin effective HIV/AIDS education and most importantly, they mobilised community and church leaders, who openly advised people on how to stay free from HIV/ AIDS.

At about the same time, the slogan of ABC (Abstinence Being faithful and Condoms) and zero grazing was introduced.

Young people were encouraged to wait until marriage before having sex and to abstain. All sexually active people were given the message of ‘zero grazing', which meant staying with regular partners and not having casual sex.

Those who did not abstain were encouraged to use condoms, which were promoted to the population as a whole.

In 1987, Noerine, together with her husband Christopher Kaleeba, mobilised others who were affected by the disease and founded TASO. Their objective was to reduce stigma, care for people living with HIV/AIDS and educate the public about the disease.

Christopher later died of AIDSrelated infections. He got the virus through blood transfusion following an accident.

On April 13, 1989, the late Philly Lutaaya Bongoley after returning from Sweden, declared that he had AIDS. Ugandans received the news with shock, but Lutaaya went around the country raising awareness and advising people to concentrate on protecting themselves, rather than cry over his fate.

To strengthen the campaign, Lutaaya composed the song, Alone and Frightened. The message was that Ugandans should stand up and fight HIV/AIDS.

Skinny and bonny with a long beard, Lutaaya sang this song wherever he went, making his audience sob and shed tears. His testimony and songs helped to encourage other HIV-positive people to open up.

This was the most dramatic way to deliver the message about HIV/AIDS.

In 1992, the Uganda AIDS Commission was established by a Statute of Parliament under the Office of the President to ensure a focused and harmonised response towards the fight against HIV/AIDS in Uganda.

It all started in a small fishing community in Kasensero, Rakai district in 1982

Going forward

"Strive to stay HIV-negative, but should you test HIV-positive, start treatment and take it faithfully as it keeps you healthy and you are not able to spread the infection to other people," says Musoba.

Statistics

According to the UNAIDS 2017 estimates, the new infection rate stands at 50,000. The Uganda Population Based HIV Impact Assessment report 2017, indicates that annually 20,000 people die of HIV and less than 4,000 babies are born with the HIV every year.

In terms of prevalence, the same report indicates a reduction from 6.2% to 7.3%, which Dr Nelson Musoba says is still unacceptably high and that the battle is not yet over.

Cases in the US

Research estimates 1969 as the year one of the first cases of HIV was registered in the US. It was the year a St. Louis teenager died of an illness that baffled his doctors.

Eighteen years later, his samples were tested and there was evidence of HIV. Another early case of AIDS in the US, was of a baby born in New Jersey in 1973 or 1974 to a 16-year-old girl who had multiple sex partners. The baby died in 1979 at the age of five.

Subsequent testing on her stored tissues confirmed that she had contracted HIV.

Also related to this story

Is cancer the new face of HIV/AIDS?

HIV/AIDS pandemic lingers despite successes