UPE: Who let go of the reins?

Jul 17, 2014

In1997 Ugandan primary schools children started the new academic year with vigour and hope. At last a new era in education had dawned. Primary education was free and all that was required was for every child regardless of age to walk to a school next to where they live.

At the time Universal Primary Education has received so much attention, most of the time for bad reasons emanating from the low quality of education and demand for more funding, a number of people have called for its overhaul and others for its closure. Is it the right way to go? Stephen Ssenkaaba, Conan Businge, Ronald Mugabe, Carol Ariba, Jonathan Angura & Angel Musinguzi sought the opinion of Government, experts and the community members on the best answer for these queries.

Is it turning-point time for free education?

By Conan Businge

In1997 Ugandan primary schools children started the new academic year with vigour and hope. At last a new era in education had dawned. Primary education was free and all that was required was for every child regardless of age to walk to a school next to where they live.

From then on, the child was to study freely till the primary cycle was completed. To ensure full and quality participation, the Uganda Government started providing funds for purchasing of all teaching learning materials, teachers' salaries and funds for capacity building. All levies and fees hitherto charged in primary schools as fees were abolished.

There were sighs of relief, celebration and praises for the new programme all over the country. Seventeen-years later, more schools have been built, many more teachers trained and pioneers pupils of this programme have graduated and are now working in and out of the country but there are also more complaints than commendations.

Failures, half-baked graduates, hungry pupils, frustrated parents, angry teachers is often the image critics depict of the Universal Primary Education the programme which started to extend access to education to all Ugandan children.

Cynics have got a field day twisting slogans to suit their urges. “Bonna basome (local speak– for free education for all) has become bonna bakone (education to fail all).

Some educationists and education activists believe that the implementation of free primary education was faulty and therefore requires an overhaul.

One senior official in the education ministry, on condition of anonymity, concludes that, “In future, Government may not even be able to fund free primary education; especially as donor funding is reducing. It is gradually weighing on Government.”

Aid to education is seriously declining in the Sub-Saharan region.

It fell by just over 6% between 2010 and 2011, and a further 3% in 2012. Basic education – which enables children to acquire foundational skills and core knowledge – is now receiving the same amount of aid as it was in 2008. But as funds diminish, just one year before the deadline for achieving the global Education for All goals, thousands of children are still out of school.

Uganda has 700,000 children out-of-school; which is 29% of the total population of children at school-going age. According to the 2014 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation report, Uganda ranks as the 11th in the world with the highest number of children out of school. As a result, there is fear that the 2015 Millennium Development Goals on education may not be met.

Primary school in Arua. Millions of pupils turned up at school when free primary education started.

The paper shows that aid is still vital for many countries, making up over a quarter of public education spending in 12 countries. Yet with aid flows to the sector falling by 10% – far more than the 1% decrease in overall aid levels – donors are clearly backing away from education as a development priority.

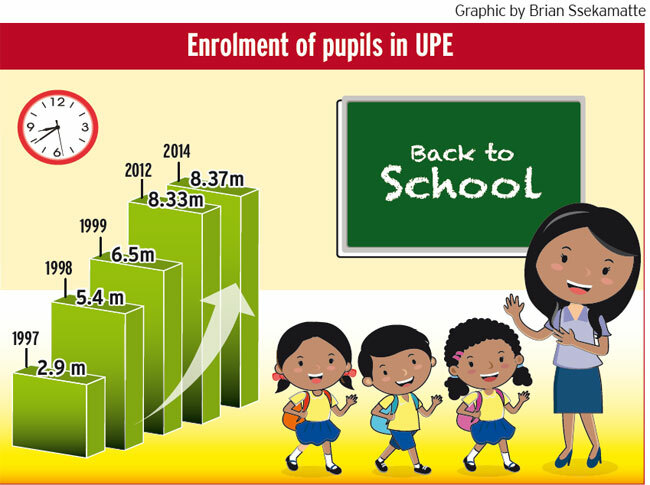

Meanwhile, the enrolment of pupils in free education is going up. Statistics show that in 1997 to 1998 the enrollment at primary school level dramatically rose from 2.9 million to 5.4 million.

The numbers increased to 6.5 million in 1999 and 8.3 million as of today. Much as there has been a growing rate of enrolment in the last 10 years, reports obtained from the education ministry show that the growth of UPE enrolment has been relatively low at 8%, compared to the growth rate registered in private primary schools that stands at 76% over the same period.

However, increment in numbers has not matched improvement in quality of the products. Studies by Government and non-government organisations show that more and more children are not indeed meeting the required competence levels.

Schools, teachers, pupils and parents are facing a myriad of difficulties and there are already suggestions that public funds may be wasted on free primary education.

However, the former education minister, who was also one of the main architects of UPE’s implementation Namirembe Bitamazire will not listen to any detractor.

“The implementation formula was correct. We got it right from the start. I have no doubt on that,” she says.

She blames parents and the community for neglecting their responsibilities and leaving all responsibilities to Government.

“This is wrong. We need serious sensitisation of the country about the value and responsibilities each of us has in this programme,” Bitamazire explains.

She also argues that the “teachers’ proficiency and efficiency needs to be stepped up, since almost 40% of the time in schools in UPE is being wasted.”

Asked about the Government’s inadequate funding, she says, “Even what is being invested is being wasted. Why ask for more funds. We should start by efficiently using the available resources,” she strong notes.

Maj. (Rtd) Jessica Alupo who took the Education ministry baton from Bitamazire strongly believes that free primary education has attained several positives on enrolment, infrastructural development, teachers’ pay and recruitment and educating thousands of Uganda; and that the remaining can always be resolved. “This programme cannot be crashed. It is here to stay.”

“We will get this right. Uganda has had its own challenges like many other African countries, but that is not the end of the road. We are committed on having progressive improvements, which will improve the quality of primary education,” reassures the education minister Maj. (Rtd) Jessica Alupo.

The Government is confident that, with more parents’ involvement in education of their children, additional funding and more infrastructural set-ups in schools, the quality of education will improve.

Interventions

Interventions To increase the number of schools, Government has been taking over community schools and constructing more classrooms, with the support of donor funding.

The Government has for years been granting aid to community and private schools annually, as a way of improving the quality of education.

The total number of schools (both private and Government) were increased from 17,679 in 2012 to 17,899 in 2013, according to the education ministry’s statistics. This has led to expansion in access by 0.6% in enrolment from 8,337,069 in 2012 to 8,390,674 in 2013.

The number of classrooms at primary school level has also grown to 147,352 in the current financial year. “There has been a continued provision of more textbooks, computers, and classroom constructions in every financial year,” Alupo explains.

The education ministry reports show that there is an initiated five-year plan to refurbish all dilapidated classrooms.

This will be done in phases starting with 2,554 primary schools; some of which are already under renovation. There will also be the construction of about 2,000 latrine blocks. The Government also plans to set up 1,000 washrooms in 1,000 schools.

Last year, according to the education ministry, 2.4 million copies of core textbooks and teachers’ guides were procured and distributed, 486 secondary schools were rehabilitated and constructed, and that construction works are on-going at an additional 639 schools.

The education ministry set up more teacher training colleges and more have been budgeted for in the current financial year.

Dr. Daniel Nkaada the commissioner for primary education says that in the last five years, there have also been curriculum reviews for both primary and secondary sections; all meant to improve the quality of education.

Main among reviews has been the introduction thematic curriculum for lower primary classes (P.1 to P.3), which was followed by the middle and upper classes of primary. A review of the secondary curriculum is still ongoing.

Alupo notes that teachers in hard-to-reach now receive an extra pay of 20% of their salaries and Government has just increased most low salary scale primary teacher’s pay by 25% in the new financial year; following the 15% pay hike two years ago.

Last year’s national financial budget main highlights in the education sector were the expansion of skills development through the Business Technical and Vocational Training and Education, increase of teachers’ salaries and a desire to reduce unemployment and boost the economic growth by starting the Youth Venture Capital Fund and Graduate Venture Capital Fund.

Almost all these programmes have been maintained this financial year, though focus was on the Students’ Loan Scheme, Teachers’ Savings and Credit Cooperatives, and accelerating government investment in vocational and business training.

Other priorities include providing adequate infrastructure in schools, in-service teacher training, and strengthening supervision of schools to improve the quality of teaching and learning.

“Some funds will be used to support science and research development, encourage the private sector to support science education and equip more schools with science laboratories,” according to the education ministry.

The director for basic and secondary education Dr. Yusuf Nsubuga says that the ministry is also already trying to address the high dropout rate in primary schools, especially among girls.

In the new budget the Government also intends to bridge the gender gap by emphasising friendly school environments for girls such as separate sanitary facilities and non-tolerance to sexual harassment.

In regard to lunch in schools; last year, it became official that schools could now charge lunch fees, if parents cannot provide food to their children. Government lifted a ban on paying lunch fees.

Government resolved that all parents should pay fees, or contribute food in kind to schools to prepare meals for their children.

The new guidelines issued were in conformity with Education Act, which in one of its sections, states that, “The responsibility of parents and guardians shall include providing food, clothing, shelter, medical care and transport…”

UPE still alive: Time to get back to the ABCs...

Prof. Venansius Baryamureeba, former Makerere University vice chancellor who has widely researched on free education in the country says that, “the Government should concentrate on funding core issues under UPE and parents should be sensitised about their roles in this programme.”

He explains that the programme has been very vital to the country, educating so many children, and “should not be sent down the drain.”

Paying attention to inspection of schools, proper training of teachers and proper remuneration will be vital if we are serious about improving the quality of education,” Prof. Baryamureeba adds.

Meanwhile, Samuel Aisu, a teacher at Buganda Road primary school in Kampala city says that to improve UPE, more teachers must be recruited and well remunerated. He appreciates the pay raise for primary teachers, much as he also adds that it is not yet enough. “Teachers also need to be well-facilitated with instruction materials in class.”

He also believes that it is wrong to have automatic promotion of pupils, in the name of saving Government resources.

“Why are pupils who have not reached a certain competence level be promoted? This is one of the issues watering down the quality of free primary education.”

Okecha Kapondo, a parent in Kampala city’s suburb says that he has children under free primary education and free secondary education, but finds the latter well managed.

“In primary schools, we are never given an opportunity to participate in the running of schools, as it is under Universal Secondary Education,” he says.

“Under USE, we sit down with the school administrators on the best plans for our schools. This is not the case with UPE schools, where head teachers are so much in control of the schools,” Kapondo says, adding that “teachers should also be allocated a lunch allowance.”

Pupils also believe that it will require more Government intervention and parents’ involvement, to improve the quality of UPE.

Dan Nkutu a pupil from Buganda Road primary school also says that it is very hard to concentrate in class on empty stomachs, after lunch. “This lunch issue is always just debated and there is no clear solution,” he laments.

David Sengendo, the Chairman of Uganda Primary Schools Head Teachers’ Association says that UPE has been a successful programme, considering the key concerns it was meant to address on its inception in 1997 – saying that there included access, equity, quality and relevance.

He notes that Government must improve the teachers’ terms and conditions of service to improve the quality of education under UPE.

“Let the teachers be paid promptly, however small the salary could be. Let the Government also disburse the capitation grants on time because unlike urban UPE schools that might have the opportunity to run on externally sourced funds, the rural head teachers find it hard to run the schools without any funding.”

He also believes that there is need for attitude change amongst the population.

“Most people think that UPE is a failed programme and does not help pupils pass national examinations. This is a wrong perception that needs to be changed,” he says.

With so many schools grappling with inadequate and delayed funding on top of delayed payments for teachers, Angella Nabwowe, an activist under the Initiative for Social and Economic Rights says: “Adequate financing is critical for improvement of UPE.

Government must be able to mobilise resources, to ensure that schools are well facilitated in terms of the capitation grants, teachers' salaries are adequate and paid on time and that the schools infrastructure is constantly upgraded.”

She also notes that schools need adequate text books. More so, she adds that there must be an efficient supervisory mechanism to oversee UPE implementation to ensure that and ensure that there is no misuse of funds, and all officers and teachers are efficiently carrying out their work.

Nabwowe adds that proper training of teachers and commensurate remuneration is a must if we are interested in improving the quality of education in the country.

She also adds that the curricula have to be revised to meet the needs of the country; on top of sensitising parents about their roles and responsibilities in education their children.

Should we overhaul or just close down UPE? Will the quality of free primary education in the country, two decades down the road improve; to give pupils like Carol Amoding and her teachers a good future?

“We know that we used the right formula to kick off this programme and we just have to resolve a few mistakes at hand, for the quality to improve,” Bitamazire asserts.

Related Stories